In recent years, “efficiency innovations” have been actively pursued by corporations, thus creating a productivity imbalance due to a lack of investment in “market-creating innovations”. We examined this in a recent article titled “Innovation – Too much, or too little of a good thing?”. On one hand, Efficiency gains have lead to 60+ year highs in corporate profit margins. On the other hand, we have seen the U.S. labor force participation rate languish at 38 year lows.

We use the example of automated supermarket check-out registers to help differentiate efficiency innovations from market-creating innovations. Automated checkout registers are a great innovation for supermarkets as fewer employees are needed to staff the store while sales remain the same, thus boosting the store’s net income. The problem with these automated registers, and more broadly efficiency innovations, is that they do not increase economic productivity over time. Efficiency innovations are “one hit wonders”. Market-creating innovations such as the computer or steam engine, on the other hand, create jobs, companies and industries and most importantly, economic growth and other innovations for decades to come.

A big reason for the imbalance between efficiency and market-creating innovations is the effect each has on short-term corporate performance measures. Market-creating innovations require substantial capital. While these innovations can have a much larger economic benefit, a longer time frame is required to realize that benefit. In the near-term, performance ratios are not enhanced and may be hurt which is detrimental to executive compensation. Meanwhile, capital deployed backing efficiency innovations has a quick and positive impact on performance ratios, impresses Wall Street analysts and rewards executives indirectly through higher stock prices.

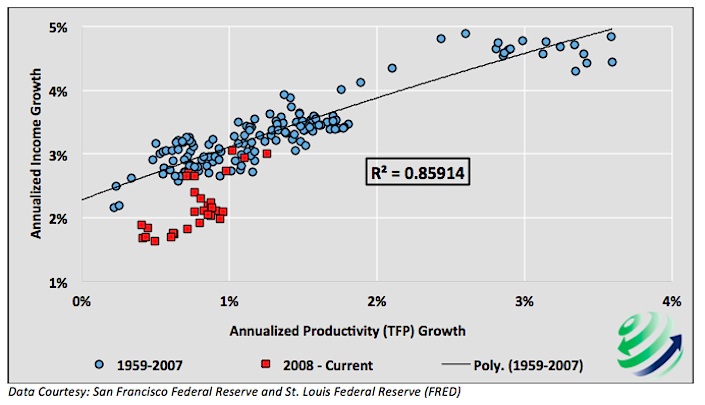

As a result of a substantial emphasis on efficiency innovation and an absence of market–creating innovation productivity growth in the U.S. is nearly flat and wages have stagnated. As efficiency innovations proliferate, workers are laid off and the supply of labor increases relative to the demand for it. Absent market-creating innovations, workers have fewer job opportunities and must be willing to work for less, if at all. The scatter plot below shows the strong correlation (R-squared = 86%) between income growth and productivity growth.

Productivity Growth vs Income Growth – 10 Year Moving Averages

It bears mentioning that personal consumption represents nearly 70% of GDP. With little recent productivity growth and little foretelling a change in this trend, we are left with yet another factor responsible for stagnating economic growth in the future.

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.