Active portfolio management, at its core, is the quest to outperform or beat the market.

While some active managers focus more on better controlling risk relative to a passive index, the majority are trying to win by generating alpha. Alpha is simply the difference between the portfolio’s return and its appropriate passive benchmark.

The strategies implemented by active managers in their search for alpha are very diverse, to say the least. The one commonality is: managers are trying to own companies that they believe are mispriced by the market and will outperform, while attempting to not own (or short for those with the latitude) companies that will underperform. This is a simplification of the complex portfolio management process, but the crux is: active managers are attempting to find and profit from mispriced companies.

The vast majority of active management approaches focus on the underlying investment (logical right?). Fundamental approaches attempt to determine what a company should be worth, and if it’s different than the market price, then see if there is an opportunity. Quantitative methodologies determine factors that have driven performance in the past and design portfolios around these factors (again we are simplifying here).

The quantitative approach is trying to math it up and solve the market. But the market changes based on the changing behavior of market participants (aka investors). This complicates things as a solution or successful strategy today may not work tomorrow. This is why continued outperformance proves so elusive.

Given market participants and their changing behaviors determine asset prices, it is the next logical step for active managers to incorporate investors behavior into their process. Focus not just on the underlying investment, but the impact of behaviors of the market participants.

Value, Growth and Quants

Value focused active managers are trying to find companies the market is neglecting, and based on their analysis, should be worth more. Active growth managers are looking for companies that the market is mispricing due to underappreciating its growth prospects. Both are running financial models that calculate an intrinsic value for companies and buying those with the best upside within their respective styles. And everyone likes a good Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model.

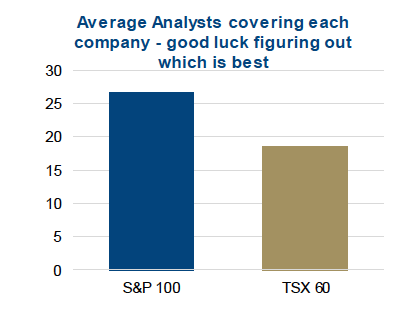

Consider this: there is an average of 26 analysts covering the companies in the S&P 100 and an average of 19 analysts covering TSX60 constituents.

Add to these groups the buy side analysts who likely outnumber the sell-side analysts by a multiply. Each of these analysts likely run detailed, well developed DCF models. Sorry research associates, they are usually the individuals updating these models, your late hours may be in vain. You are trying to solve something that can’t be solved because human behavior changes and this changes share prices. With 50+ models, often with conflicting conclusions, how do you figure out which ones are right and which are wrong. Good luck!

Don’t get us wrong, fundamental research and model development does provide a social benefit. It does increase market efficiency, price discovery and provide more accurate pricing of assets. But, if you believe this is an edge to outperform the market and other managers, you may want to reconsider, even if you believe you have the ‘best’ model ever.

Quantitative portfolio management approaches differ somewhat. In most cases, these attempt to harvest a certain factor or combination of factors that have shown some efficacy in beating the market.

An example could be targeting value factors, such as low price-to-earnings and low price-to-book. Instead of designing individual company models, they build portfolios of companies that score well based on these factors. This approach supposes that the selected factor or factors will continue to work in the future.

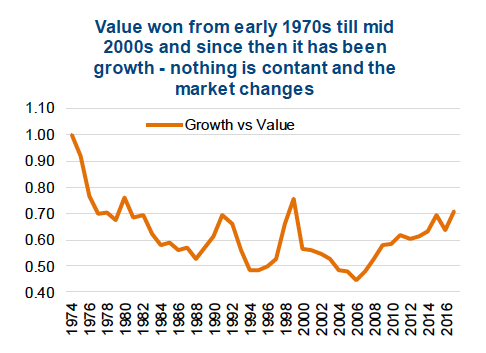

Many speak of the ‘value premium’, value factors that have historically shown to outperform. However, this implies the factor will remain constant or a reliable source of alpha. We would challenge this thinking because, if more managers and capital is committed to this approach, the alpha will be shared across more managers, reducing the benefit to each manager. Sharing is good, but not when it comes to alpha.

Value dominated growth in most years from 1974 till the mid 2000s. But remember that value managers, both fundamental and quant based, were not plentiful in the 1970s and 1980s. Could this scarcity of value managers during this time period be one of the reasons for the strong outperformance? There are many value managers today, and

from a style perspective they have been lagging. This seems to suggest that the changing behavior of the market participants, has changed the market.

To beat the market, you need to not just have a good process, but also be different. If most are focused on value, or dividends, or growth, being part of the herd is an easy path to herd like performance and we know that the herd rarely wins.

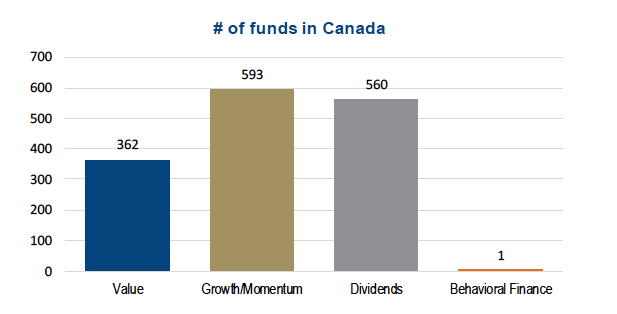

The next chart is based on Bloomberg classifications of style for funds available in Canada. There are many value, growth and dividends funds…..and only one behavioral finance based fund.

The Market is a Social Science, and is not Solvable

While we are fans of math, investing is actually more of a social science, not a hard science. Physics is a hard science, that is based on usually testable theories, quantifiable and with accurate models. Social sciences are more the study of human society and social relationships. Given investors actually change behavior and those changing behaviours change the market, this makes models based only on numbers less reliable. This is why portfolio managers are often less accurate than meteorologists. Both have to deal with predicting very complex systems with many moving parts. But the weather person’s forecast cannot change the weather. If they say it will rain and everyone brings an umbrella to work, this doesn’t change the probability of rain. If a portfolio manager or market forecaster says its going to ‘rain’ and everyone behaves differently, the market itself will change.

Portfolio Management Implications – If you agree that active portfolio management is the quest to find and profit from mispriced assets, managers should start to focus more on the behavior of agents or market participants (aka other investors).

In many cases the emotionally driven behavioral mistakes of other investors can create mispriced assets. This can take the form of recency bias, placing too much importance on what has just occurred over a longer-term perspective. Or herd behavior around trendy thematics. We are not saying traditional approaches are in their twilight, instead they should evolve to directly incorporate behavioral mistakes. As the manager of the only Behavioral Finance fund in Canada, perhaps we are not objective. But we are certainly not part of the herd.

Charts are sourced to Bloomberg unless otherwise noted. Growth vs Value is based on S&P 500 Growth & Value Indices. # of funds based on Bloomberg Fund Screen

Twitter: @sobata416 @ConnectedWealth

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.