In “What Me Worry” I noted that the closely watched VIX equity volatility index (INDEXCBOE:VIX) was at a level of investor complacency rarely seen. This is true not only in election years but over decades of market history. We also mentioned anxiety surrounding the upcoming election is palpable. And further, that equity valuations are at rarefied levels without supporting earnings and economic data.

Given these factors we ended the article with the following: “The market, courtesy of complacent investors, is offering very cheap insurance for an event that has the potential to induce extreme volatility via VIX options and futures. Even if the next eleven weeks leading to the election prove to be uneventful, the VIX at current levels, as shown earlier, has been a prudent place to own protection”.

Unfortunately, most professional investment managers are not adept and/or able to trade VIX futures, options or volatility in other forms to hedge their client’s equity positions. More often than not, concerned managers will instead reduce perceived risk by selling a portion of their equity holdings and increasing cash positions and/or shifting portfolio allocations from equities to fixed income. It is in this vain that we discuss how the latter option, shifting money from equities to fixed income, has risks that were not as evident during the 2000 tech crash and the 2008 financial crisis.

Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT)

Harry Markowitz developed the Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) in the 1950’s. Simply put his theory argues that portfolio risk can be reduced by holding combinations of different securities and asset classes that are not positively correlated. We agree with the theory that there are benefits to diversification but we do not subscribe to MPT. Diversification makes sense when you buy uncorrelated assets that are undervalued. Buying assets for the sake of diversification without regard for valuation is fraught with risk regardless of how many different securities and asset classes one may hold. In the words of Warren Buffett “diversification is a protection against ignorance. It makes very little sense for those that know what they are doing”. To paraphrase Warren Buffet, diversification is for those that do not know what they are doing.

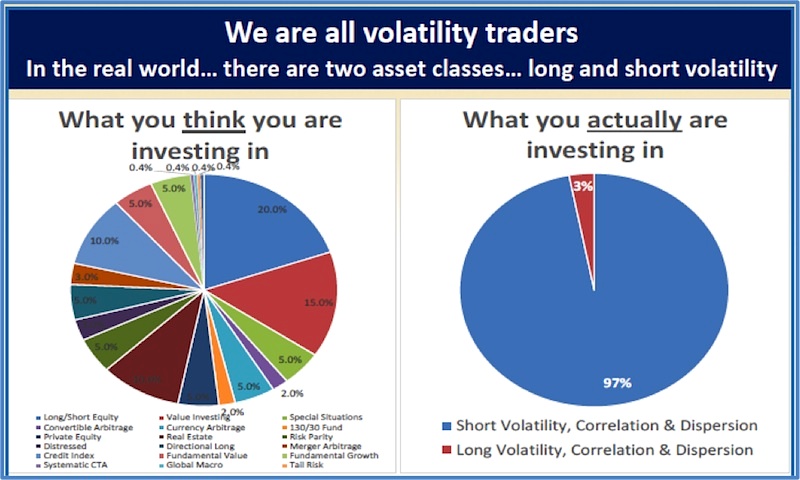

The truth of the matter is that blind diversification does not work simply because it does not take into account the effects of volatility on asset prices. Chris Cole from Artemis Capital, one of the clearest thinkers on the importance of volatility as an asset class, highlights this point in the following graphic.

Contrasting the perception of a well-diversified portfolio with the reality of embedded volatility, the graph reflects enormous concentration risk in short volatility. Importantly, this risk matters most at the exact point in time when one expects – hopes – their strategy of diversification will protect them. Unfortunately, the well-diversified portfolio (left side) turns in to the short volatility-concentrated portfolio in periods of extreme market disruption. Mr. Cole’s analysis may be best summarized with the popular statement that correlations on many assets go to one during a crisis.

Without regard for Mr. Buffett’s or Mr. Cole’s perspectives, many investment managers tend to hold “diversified” portfolios of stocks and bonds in various forms and strongly believe that such diversification will protect their portfolios in the event of a serious market correction. Unfortunately, many investors are not basing this diversification strategy on a fundamental analysis of bonds but largely on a blind assumption that bond prices will rise – yields will fall – in the event of trouble in the equity market.

Bonds

Sovereign bond markets around the world are trading at their lowest yields in decades and in some instances, including in the United States, in centuries. In fact there are approximately $13 trillion worth of global bonds that have negative yields.

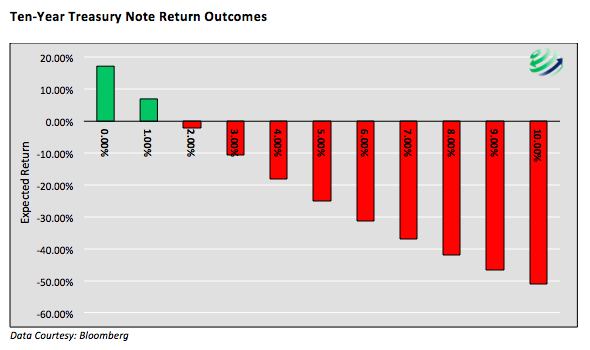

Bond investors today are faced with a unique problem resulting from these low yields. The potential for price increases versus price decreases is grossly asymmetric. In other words there is a lot more money to lose in bonds than can be made. To illustrate this consider a ten-year U.S. Treasury note maturing in August 2026, with a coupon of 1.50% annually, a price of 99.25 and a yield of 1.58%. The chart below shows a range of potential one-year total returns for various yield levels in the ten-year note described above. As a frame of reference the average yield during the 2008 crisis was 3.43%. If the yield on the current 10-year note were to rise to that level in a year an investor would suffer a loss of 14%.

continue reading on the next page…