This post was written with Chris Kerlow and Craig Basinger.

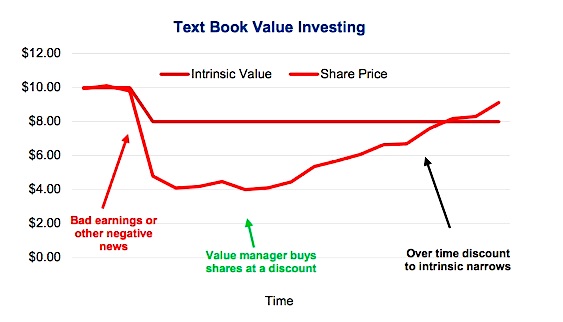

The essence of money management can be encapsulated in searching for investments that are trading below their intrinsic value.

In theory, it works like this: Buying these companies low, and as the market comes around to realize their intrinsic value, the price moves higher and we sell for profits.

This is the activity of price discovery and makes for a healthy market as participants buy and sell in the attempt to profit from the return to intrinsic value, see chart. But there is a new big player in the market that doesn’t care about price discovery, the Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) or other passive index investment strategies. A passive ETF is price agnostic. They need to buy the shares of the underlying basket of stocks that comprise the index, regardless of the price of those stocks. Their mandate is not to buy low, sell high; it is to buy quickly, minimizing tracking error, giving investors the exact exposure they are looking for. Most indices are based on market weight, and do not discriminate for liquidity.

With ETFs swelling in assets and active managers shrinking over the past years, the number of participants embarking upon the admirable task of price discovery is lower. All else equal, this suggests it will likely take longer for the true intrinsic value to be found. Meaning that the Warren Buffet style investors will need to wait longer for the tide to go out and show who is swimming naked, as the oracle from Omaha eloquently once said. This could be one of the reasons why active management has lagged for the past several years, as the bull market marches higher and passive funds pile more and more capital into the fastest growing stocks, with no regard to price or value.

Active managers typically classify their style into specific architypes. Value investors buy beaten down companies that are believed to have a larger gap between the current price and intrinsic value. Growth managers buy at higher levels, thinking that the market is underestimating the growth prospects. Top down managers make macro bets, focusing on sector allocation and picking the best solution to portray their view. Or, a manager might focus on specific factors like large cap, dividend companies which narrows their focus and inherently investment outcomes.

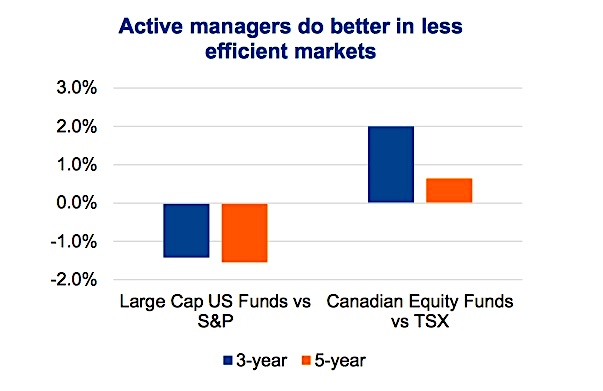

All things considered, most managers use a varying combination of different approaches. All are buying companies they believe to be below intrinsic value and selling those at or above intrinsic value. But with a weaker price discovery mechanism in the market, perhaps it is time for active managers to change their approach. We believe active managers can add the most value when the market is inefficient – see chart below. And inefficiencies are often caused by human behavior.

Where do these inefficiencies stem from? The innate human behaviors that have helped us survive and work our way to the top of the food chain also come with flaws that are exhibited in investing. We are accumulating a variety of research on these biases and looking for investing opportunities that these repeating tendencies present. We will highlight several of these behavioral biases to help our readers try to avoid them in their own portfolios and potentially profit from taking advantage of others irrational behaviors.

Overreaction

Markets are largely efficient, some more than others, but it is undeniable that inefficiencies are present. Some inefficiencies take time to rectify themselves and some come and go quickly. These aberrations are highlighted by the market’s reaction to earnings and brief periods of extreme volatility (flash crashes).

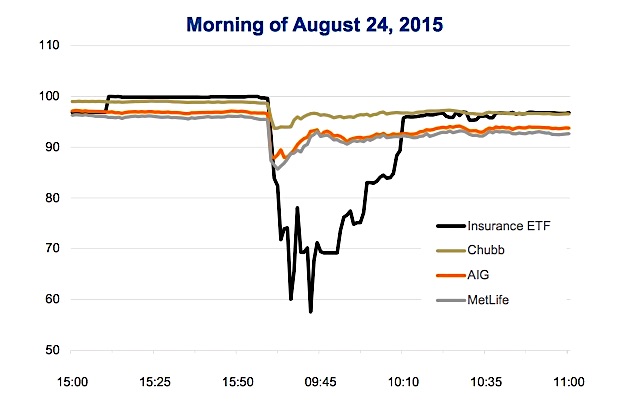

As an example, during the May 2010 flash crash, we saw the U.S. market lose a trillion dollars of market cap in 36 minutes, only to rebound quickly thereafter. It would be interesting to hear Eugene Fama explain how that is a characteristic of an efficient market. Regulations were put in place to avoid such an event from occurring again (LULD) but they proved to be inadequate. On August 24, 2015 we experienced another flash crash with many ETFs becoming unhinged from their implied value. The limit up, limit down (LULD) regulations put in place during the previous flash crash exacerbated the problem as market markers of ETFs were uncertain of the true value of the basket that investors were trying to buy / sell, so the market makers vanished.

We vividly remember sitting at our desks that Monday morning as the Dow fell 1,000 in just minutes. What caught our attention more than the massive fall in stock prices, was the dislocation between sector ETFs and the basket of stocks they were built to follow. IAK, the iShares insurance ETF was down 42% in the first 12 minutes of trading, while at the same time the largest underlying constituents like AIG and MetLife were down only 10%. The market makers had seemingly disappeared. Everything did come back to reality just a short while later as the ETF rallied 68% off the lows, as shown on the chart below.

Although this exact scenario may not happen again, over reaction to new information will. This stems from the availability heuristic where investors focus on the most recent information often ignoring the long term picture. Our Market Ethos on Earnings Overreaction, goes into detail on how high quality companies that see a share price slammed on a negative earnings report tend to make back the share price loss quickly, while low quality companies that gap up on earnings tend to give back the gains.

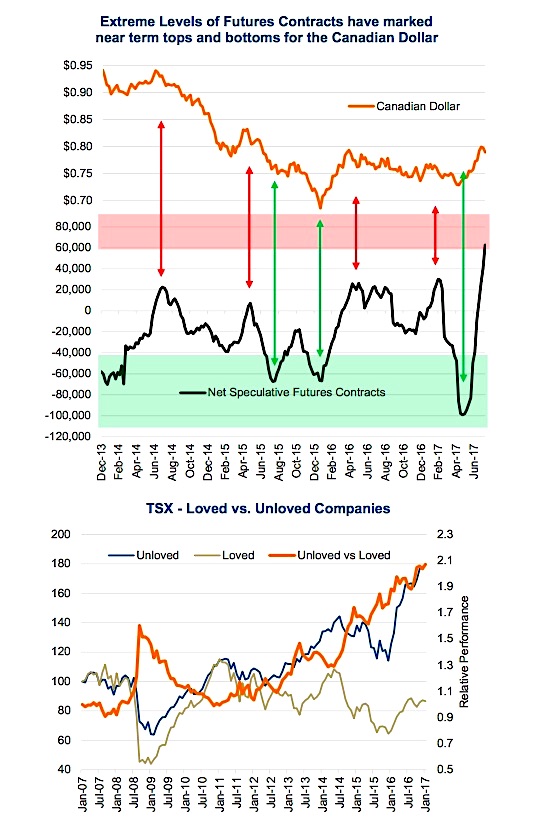

Confirmation Bias and Herding

Two weeks ago we wrote about the flaws in investing with the herd. Our innate tendency to follow the herd has been ingrained in us through Darwinism and is glaringly obvious in investing, but often ends poorly, especially for those late to the party. The next chart exemplifies what we are referring to. You can see when the herd, in this case speculators on the Canadian dollar, gets to extreme levels, it has been the exact time the momentum shifts in the other direction. Adding to this problem is a confirmation bias, when investors place more value on information that corroborates with their own opinion. The flaws are simply human nature and unlikely to go away anytime soon.

Understanding that, if you are able to get in early before the herd follows, you should be able to make some nice profits. To do so, you need to take a contrarian view, which conflicts with the comforting feelings you get from going with the herd. Back in April, we published a piece that outlined a strategy to take advantage of these biases. Best to be Unloved goes into greater detail but the idea is simple: companies that are largely unloved by the analyst community, but then start to get upgraded, have seen outsized gains versus companies that have mainly buy ratings, last chart. The premise is rather simple, these unloved companies could have depressed valuations because they do not have the herd supporting the stock. Then as analysts start to recognize a change in business fundamentals, they upgrade the stock. Often other analysts follow their peers, subsequently upgrading their rating of the stock. More upgrades tend to follow, giving investors confirmation and feeding the herding behaviour.

Conclusion

These are just a couple of examples of how our hardwired heuristics and bias show up in investment decisions. We are engulfed in the subject matter as we continue to research behavioral finance to help avoid pitfalls in our own investment process as well as find ways of exploiting these repeated flaws exhibited in the broad market. We look forward to sharing the findings with you, our readers, to help you avoid making behavioral mistakes.

Charts are sourced to Bloomberg unless otherwise noted.

Twitter: @sobata416 @ConnectedWealth

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.