“You load sixteen tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

Saint Peter don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go

I owe my soul to the company store”

– Sixteen Tons by Tennessee Ernie Ford

Shortly following president Donald Trump’s election victory we penned a piece entitled Hoover’s Folly. In light of President Trump’s introduction of tariffs on steel and other selected imports, we thought it wise to recap some of the key points made in that article and provide additional guidance.

While the media seems to treat Trump’s recent demands for tariffs as a hollow negotiating stance, investors are best advised to pay attention. At stake are not just more favorable trade terms on a few select products and possibly manufacturing jobs but the platform on which the global economic regime has operated for the last 50 years.

So far it is unclear whether Trump’s rising intensity is political rhetoric or seriously foretelling actions that will bring meaningful change to the way the global economy works.

Either as a direct result of policy and/or uncharacteristic retaliation to strong words, abrupt changes to trade, and therefore the role of the U.S. Dollar as the world’s reserve currency, has the potential to generate major shocks in the financial markets.

Hoover’s Folly

The following paragraphs are selected from Hoover’s Folly to provide a background.

In 1930, Herbert Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act into law. As the world entered the early phases of the Great Depression, the measure was intended to protect American jobs and farmers. Ignoring warnings from global trade partners, the new law placed tariffs on goods imported into the U.S. which resulted in retaliatory tariffs on U.S. goods exported to other countries. By 1934, U.S. imports and exports were reduced by more than 50% and many Great Depression scholars have blamed the tariffs for playing a substantial role in amplifying the scope and duration of the Great Depression. The United States paid a steep price for trying to protect its workforce through short-sighted political expedience.

Although it remains unclear which approach the Trump trade team will take, much less what they will accomplish, we are quite certain they will make waves. The U.S. equity markets have been bullish on the outlook for the new administration given its business-friendly posture toward tax and regulatory reform, but they have turned a blind eye toward possible negative side effects of any of his plans. Global trade and supply chain interdependencies have been a tailwind for corporate earnings for decades. Abrupt changes in those dynamics represent a meaningful shift in the trajectory of global growth, and the equity markets will eventually be required to deal with the uncertainties that will accompany those changes.

From an investment standpoint, this would have many effects. First, commodities priced in dollars would likely benefit, especially precious metals. Secondly, without the need to hold as many U.S. dollars in reserve, foreign nations might sell their Treasury securities holdings. Further adding pressure to U.S. Treasury securities and all fixed income securities, a weakening dollar is inflationary on the margin, which brings consideration of the Federal Reserve and monetary policy into play.

The Other Side of the Story

The President recently tweeted the following:

Regardless of political affiliation, most Americans agree with President Trump that international trade should be conducted on fair terms. The problem with assessing whether or not “trade wars are good” is that one must understand the other side of the story.

Persistent trade imbalances are the manifestation of explicit global trade agreements that have been around for decades and have historically received broad bi-partisan support. Those policies were sponsored by U.S. leaders under the guise of “free trade” from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to ushering China in to the World Trade Organization (WTO). During that time, American politicians and corporations did not just rollover and accept unfair trade terms; there was clearly something in it for them. They knew that in exchange for unequal trade terms and mounting trade deficits came an implicit arrangement that the countries which export goods to the U.S. would also fund that consumption. Said differently, foreign countries sold America their goods on credit. That construct enabled U.S. corporations, the chief lobbyists in favor of such agreements, to establish foreign production facilities in cheap labor markets for the sale of goods back into the United States.

The following bullet points show how making imports into the U.S. easier, via tariffs and trade pacts, has played out.

- Bi-partisan support for easing multi-lateral trade agreements, especially with China

- One-way tariffs or producer subsidies that favor foreign producers were generally not challenged

- Those agreements, tariffs, and subsidies enable foreign competitors to employ cheap labor to make goods at prices that undercut U.S. producers

- U.S. corporations moved production overseas to take advantage of cheap labor

- Cheaper goods are then sold back to U.S. consumers creating a trade deficit

- U.S. dollars received by foreign producers are used to buy U.S. Treasuries and other dollar-based corporate and securitized individuals liabilities

- Foreign demand for U.S. Treasuries and other bonds lower U.S. interest rates

- Lower U.S. interest rates encourage consumption and debt accumulation

- U.S. economic growth increasingly centered on ever-increasing debt loads and declining interest rates to facilitate servicing the debt

Trade Deficits and Debt

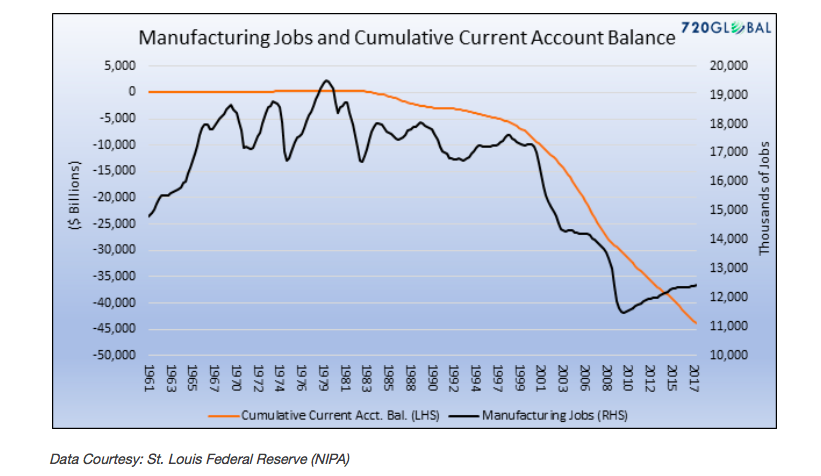

These trade agreements subordinated traditional forms of production and manufacturing to the exporting of U.S. dollars. America relinquished its role as the world’s leading manufacturer in exchange for cheaper imported goods and services from other countries. The profits of U.S.-based manufacturing companies were enhanced with cheaper foreign labor, but the wages of U.S. employees were impaired, and jobs in the manufacturing sector were exported to foreign lands. This had the effect of hollowing out America’s industrial base while at the same time stoking foreign appetite for U.S. debt as they received U.S. dollars and sought to invest them. In return, debt-driven consumption soared in the U.S.

The trade deficit, also known as the current account balance, measures the net flow of goods and services in and out of a country. The graph below shows the correlation between the cumulative deterioration of the U.S. current account balance and manufacturing jobs.

Since 1983, there have only been two quarters in which the current account balance was positive. During the most recent economic expansion, the current account balance has averaged -$443 billion per year.

continue reading on the next page…