Most traders speak today of the bull run of the mid-to-late 1990s (place Greenspan’s 1996 “Irrational Exuberance” comment right at the epicenter and you’ll know the period I’m talking about) with a far-off look of nostalgic bliss (those who were there) or a kind of wonderment and hushed veneration (from those who weren’t). The period’s mythos is entirely grounded in fact, leading right up to the full complement of outlying statistics at its peak, from the 44.2 CAPE to a NASDAQ Composite (COMPQ) blowoff and still-15-year high at 5132 (preceded by +86% in 1999), the quantity and proceeds of IPOs (480 IPOs at $61.63 Billion in 1999) among an array of other facts indicative of the teetering speculative bombast at the end.

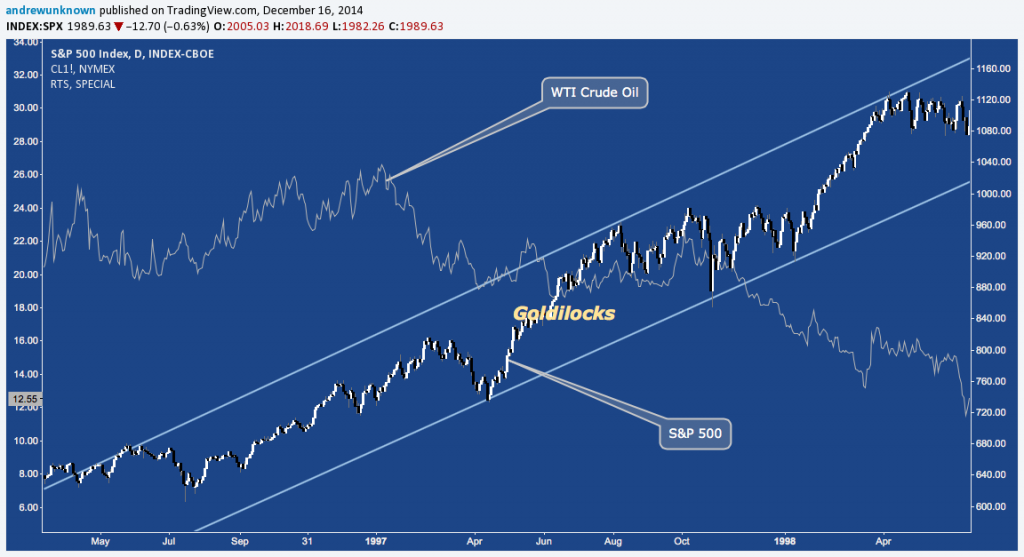

Before all sense of prudence devolved and the market lost its collective mind, however, there was an age of plenty – the proverbial “Goldilocks economy” denoted by a salutary combination advancing asset prices, low unemployment, low interest rates and inflation low enough to avert policy tightening in a context of rising corporate profits and sturdy GDP growth. Falling energy prices don’t hurt, either:

But this commonly-cited list of fundamentals omits the most important agent of all: consumers, producers and investors, firm enough in their confidence to spur the advance. The reciprocity created by confidence and improving macro markers creates a virtuous loop that feeds on itself.

The nature of feedback loops (just ask my Gibson Les Paul, olive-green Sovtek Big Muff fuzz pedal and Orange half-stack) is to rise irrepressibly until the signal reaches a shrieking apogee, at which point entropy takes over (up to and including the point where amp tubes blow out). The point where asset prices and the economy converge (and they do, occasionally) is where the reciprocity between confidence and “not too hot/not too cold” becomes so enamored of its own exchange that it misses the ravenous bear approaching the door after a wearying sojourn in the wilderness.

The death knell of the 1990s Goldilocks didn’t occur in the US, but abroad. One reading of the late 1990s is that the “failed genius” of LTCM in the US (and even more critically, the rapid negation of it) is indicative of the hubris that finally brought the bear to our door. This time, he came cloaked in the trappings of early-stage, wildly speculative tech issues to prance through the final manic steps of the game of musical chairs that abruptly halted in early 2000, some 1.5 years later.

The death knell of the 1990s Goldilocks didn’t occur in the US, but abroad. One reading of the late 1990s is that the “failed genius” of LTCM in the US (and even more critically, the rapid negation of it) is indicative of the hubris that finally brought the bear to our door. This time, he came cloaked in the trappings of early-stage, wildly speculative tech issues to prance through the final manic steps of the game of musical chairs that abruptly halted in early 2000, some 1.5 years later.

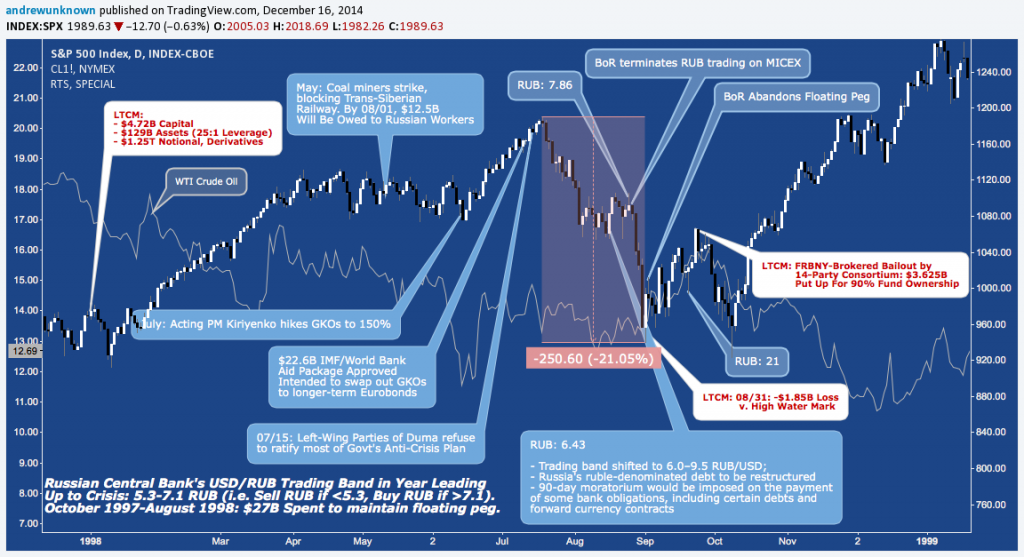

Admittedly, though: whether 1997’s Asian Contagion and 1998’s Russian Financial Crisis were an EM pre-cursor and contributor to the 2000-2002 tech bear is a highly complex question. With Russia making daily headlines on topics geopolitical (sanctions), bellicose (Ukraine) and financial (currencies, commodities, equities), let’s turn our attention there to ask the question that most, frankly, are wondering about: what impact (if any, some dismissively inquire) will Russia’s woes – clearly signaled by the staggering 650bps hike of its overnight borrowing rate to 17% – have on the blissfully decoupled S&P 500 (SPX)? What happened the last time the Ruble (USD/RUB) suffered a massive devaluation, the BoR spiked rates (strangling domestic businesses), WTI Crude Oil (CL) prices slid (highly exacerbating its current account deficit) and Russia’s equities tanked?

Here’s a timeline of the developments preceding and during the Russian Financial Crisis of Summer/Fall 1998, along with LTCM’s concurrent unraveling and 11th-hour defusal, just before it set off a shockwave of systemic oblivion with its $1.25T in off-balance sheet derivative exposure:

The prospect of a Russian default may not be particularly high at the moment, but it’s worth considering the last time we saw the Ruble, Crude Oil and Bank of Russia tumbling down the obsidian-bricked road to the Default City together.

Here we’re concentrated on that city on a hill that is the US equity market. The seemingly indomitable apparatus of the Goldilocks economy of 1998 this is not; but we might fill in the holes with today’s preening confidence in (on green days) and infantile obeisance to (on down days) Central Bank largesse to approximate the same loop of confidence and rising asset prices. Looking back, here’s what When Genius Failed author Roger Lowenstein noted about LTCM’s 1998 failure in 2008:

And Long-Term Capital’s investments were far more correlated than it realized. In different markets, it made essentially the same bet: that risk premiums — the amount lenders charge for riskier assets — would fall. Was it so surprising that when Russia defaulted, risk premiums everywhere rose?

The question of what first round impact Russia will have – or Crude, or speculative shale issues/MLPs with their lack of profits, dismembered debt and faltering equity – is really just a matter of time. The more concerning question is: what reflexivity-incited excesses are buried beneath as second or third round derivatives. LTCM’s partners opined (just before opening new funds) after their own debacle in an ambivalent rite of contrition and self-delivered absolution

Long-Term Capital’s partners were shocked that their trades, spanning multiple asset classes, crashed in unison. But markets aren’t so random. In times of stress, the correlations rise. People in a panic sell stocks — all stocks. Lenders who are under pressure tighten credit to all.

and

The fund’s partners likened their disaster to a “100-year flood”— a freak event like Katrina or the Chicago Cubs baseball team winning the World Series.

and

After Long-Term Capital’s fall, many commentators blamed a lack of liquidity. They said panic selling in thin markets pushed its assets below their economic value.

There are potential catalysts in the current market environment; and for US equities they’ve meant very little: not in spite of what’s happening in other markets (including other asset classes in the US), but – as we’re told reassuringly – because of what is happening elsewhere. Can this last? Perhaps. Are there grounds to suppose it will? Opinions differ; but the truth this context is different; just as they always are.

One thing doesn’t change, however. The virtuous cycle of the Goldilocks economy is transitory. The genius of confidence spun of the market yarn is transmogrified into a gaudy hubris, adorned with the naive excitement of whatever “disruptive” technological revolution is going on at the moment, the omniscience of data and (this time) Central Bank hegemony. Words like “shock”, “disaster” and “panic” seem far away despite peaking and deteriorating factors that are indicative of a signal decay that has been building on silent wavelengths and that will always take hold as long as human certainty drives market cycles.

Twitter: @andrewunknown

Author holds no exposure to instruments mentioned at the time of publication. Commentary provided is for educational purposes only and in no way constitutes trading or investment advice.