“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose,

By any other name would smell as sweet.” – Juliet Capulet in Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

Burgeoning Problem

The short-term repo funding turmoil that cropped up in mid-September continues to be discussed at length. The Federal Reserve quickly addressed soaring overnight funding costs through a special repo financing facility not used since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). The re-introduction of repo facilities has, thus far, resolved the matter. It remains interesting that so many articles are being written about the problem, including our own.

The on-going concern stems from the fact that the world’s most powerful central bank briefly lost control over the one rate they must control.

What seems clear is the Fed measures to calm funding markets, although superficially effective, may not address a bigger underlying set of issues that could reappear.

The on-going media attention to such a banal and technical topic could be indicative of deeper problems. People who understand both the complexities and importance of these matters, frankly, are still wringing their hands. The Fed has applied a tourniquet and gauze to a serious wound, but permanent medical attention is still desperately needed.

The Fed is in a difficult position. As discussed in Who Could Have Known – What the Repo Fiasco Entails, they are using temporary tools that require daily and increasingly larger efforts to assuage the problem. Taking more drastic and permanent steps would result in an aggressive easing of monetary policy at a time when the U.S. economy is relatively strong and stable, and such policy is not warranted in our opinion. Such measures could incite the most underrated of all threats, inflationary pressures.

Hamstrung

The Fed is hamstrung by an economy that has enjoyed low interest rates and stimulative fiscal policy and is the strongest in the developed world. By all appearances, the U.S. is also running at full employment. At the same time, they have a hostile President sniping at them to ease policy dramatically and the Federal Reserve board itself has rarely seen internal dissension of the kind recently observed. The current fundamental and political environment is challenging, to be kind.

Two main alternatives to resolve the funding issue are:

- More aggressive interest rate cuts to steepen the yield curve and relieve the banks of the negative carry in holding Treasury notes and bonds

- Re-initiating quantitative easing (QE) by having the Fed buy Treasury and mortgage-backed securities from primary dealers to re-liquefy the system

Others are putting forth their perspectives on the matter, but the only real “permanent” solution is the second option, re-expanding the Fed balance sheet through QE. The Fed is painted into a financial corner since there is no fundamental justification (remember “we are data-dependent”) for such an action. Further, Powell, when asked, said they would not take monetary policy actions to address the short-term temporary spike in funding. Whether Powell likes it or not, not taking such an action might force the need to take that very same action, and it may come too late.

Advice from Those That Caused the Problem

There was an article recently written by a former Fed official now employed by a major hedge fund manager.

Brian Sack is a Director of Global Economics at the D.E. Shaw Group, a hedge fund conglomerate with over $40 billion under management. Prior to joining D.E. Shaw, Sack was head of the New York Federal Reserve Markets Group and manager of the System Open Market Account (SOMA) for the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). He also served as a special advisor on monetary policy to President Obama while at the New York Fed.

Sack, along with Joseph Gagnon, another ex-Fed employee and currently a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, argue in their paper LINK that the Fed should first promptly establish a standing fixed-rate repo facility and, second, “aim for a higher level of reserves.” Although Sack and Gagnon would not concede that reserves are “low”, they argue that whatever the minimum level of reserves may be in the banking system, the Fed should “steer well clear of it.” Their recommendation is for the Fed to increase the level of reserves by $250 billion over the next two quarters. Furthermore, they argue for continued expansion of the Fed balance sheet as needed thereafter.

What they recommend is monetary policy slavery. No matter what language they use to rationalize and justify such solutions, it is pure pragmatism and expediency. It may solve short-term funding issues for the time being, but it will leave the U.S. economy and its citizens further enslaved to the consequences of runaway debt and the monetary policies designed to support it.

If It Walks and Quacks Like a Duck…

Sack and Gagnon did not give their recommendation a sophisticated name, but neither did they call it “QE.” Simply put, their recommendation is in fact a resumption of QE regardless of what name it is given.

To them it smells as sweet as QE, but the spin of some other name and rationale may be more palatable to the public. By not calling it QE, it may allow the Fed more leeway to do QE without being in a recession or bringing rates to near zero in attempts to avoid becoming a political lightening rod.

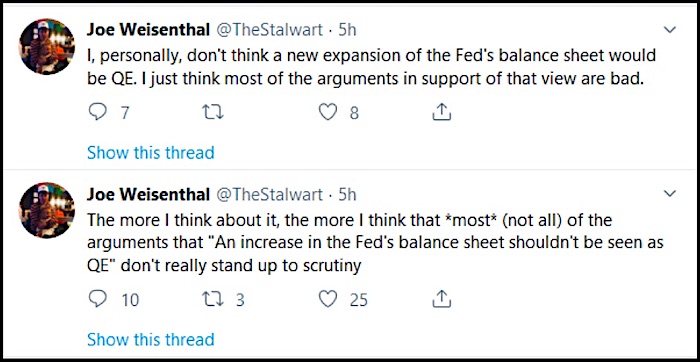

The media appears to be helping with what increasingly looks like a sleight of hand. Joe Weisenthal from Bloomberg proposed the following on Twitter:

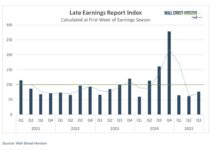

To help you form your own opinion let’s look at some facts about QE and balance sheet increases prior to the QE era. From January of 2003 to December of 2007, the Fed’s balance sheet steadily increased by $150 billion, or about $30 billion a year. The new proposal from Sack and Gagnon calls for a $250 billion increase over six months. QE1 lasted six months and increased the Fed’s balance sheet by $265 billion. Maybe it us, but the new proposal appears to be a mirror image of QE.

Summary

The challenge, as we see it, is that these former Fed officials do not realize that the policies they helped create and implement were a big contributor to the financial crisis a decade ago. The ensuing problems the financial system is now enduring are a result of the policies they implemented to address the crisis. Their proposed solutions, regardless of what they call them, are more imprudent policies to address problems caused by imprudent policies since the GFC.

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.