The labor markets have been improving steadily since the financial crisis. Some people would argue that the US is at or near full employment. Even so, there is one piece of the puzzle that is still missing… higher wage inflation.

The Fed’s mandate is to promote maximum employment and stable prices; thus, wage inflation is doubly important.

In the following sections, we will try to determine why it is not speeding up.

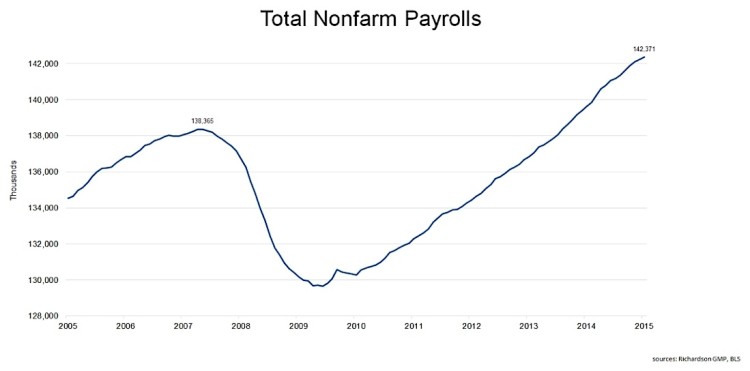

Jobs, Jobs, Jobs

At first glance, the US labor market looks unstoppable. see chart below

- The total number of employees is higher now than it was before the crisis.

- Total nonfarm payrolls rose by 12,654,000 from January 2010 to September 2015.

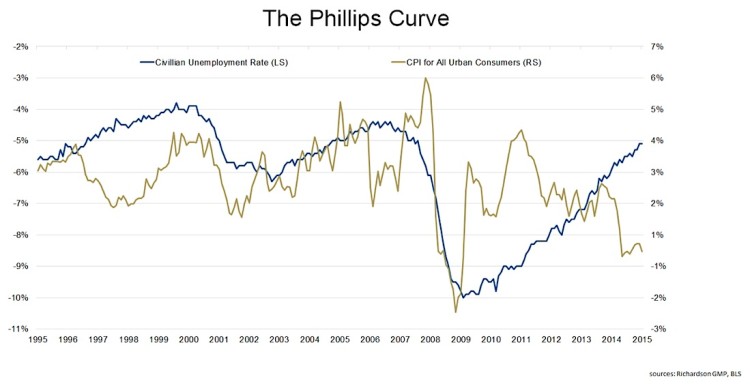

The Phillips Curve

In economics, “the Phillips curve is a historical inverse relationship between rates of unemployment and corresponding rates of inflation…”

In other words, falling unemployment tends to coincide with rising inflation. Intuitively that makes sense. If the demand for labor is higher than the supply then unemployment should fall and wages should rise. That said, the relationship has not held true this cycle. The following chart shows the unemployment rate (inverted) vs. the consumer price index:

Prior to this cycle, falling unemployment was accompanied by rising inflation, and vice versa. This time around, both the UE rate and consumer price growth have been falling.

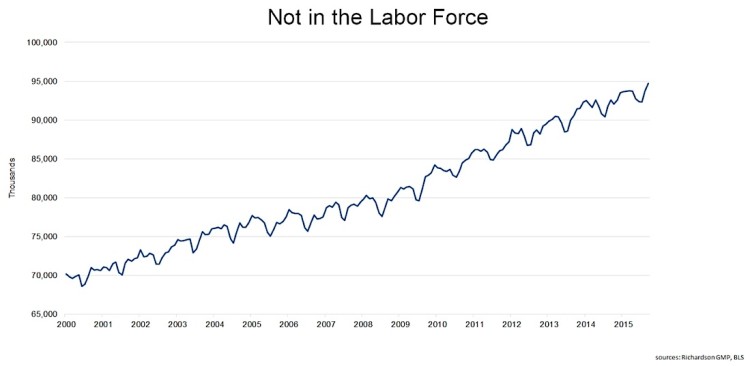

Not Participating

There are two reasons why the UE rate may fall. The first is that the number of unemployed persons (numerator) falls. That is good. The second is that the labor force (denominator) shrinks. That is bad. Regrettably, the unemployment rate has been falling for the wrong reason:

The number of people not in the labor force increased by 10,842,000 from January 2010 to September 2015.

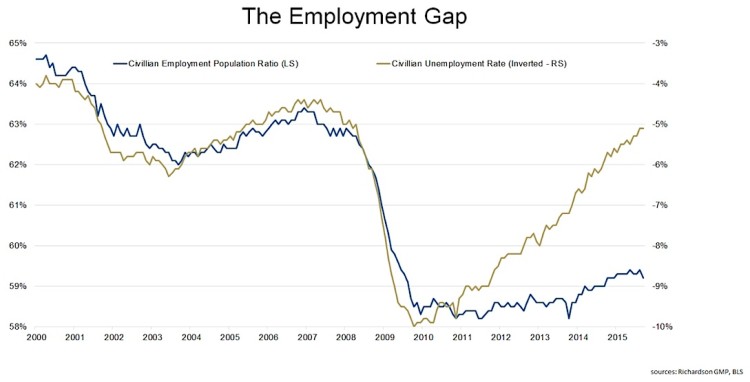

As a result, there is a growing divergence between the unemployment rate (inverted) and the employment rate, which does not consider the size of the labor force:

continue reading on the next page…