Pondering the state of the global economy can elicit manic-depressive-obsessive-compulsive emotions. The volatility of global markets – equities, bonds, commodities, currencies, etc. – are challenging enough without consideration of Brexit, the U.S. Presidential election, radical Islamic terrorism and so on. Yet no discussion of economic and market environments is complete without giving hefty consideration to what may be a major shift in the way economic policy is conducted in Japan. Is the era of helicopter money upon us?

The Japanese economy has been the poster child for economic malaise and bad fortune for so long that even the most radical policy responses no longer garner much attention. In fact, recent policy actions intended to weaken the Yen have resulted in significant appreciation of the yen against the currencies of Japan’s major trade partners, further crippling economic activity. The frustration of an appreciating currency coupled with deflation and zero economic growth has produced signs that what Japan has in store for the world falls squarely in to the category of “you ain’t seen nothin’ yet.” Assuming new fiscal and monetary policies will be similar to those enacted in the past is a big risk that should be contemplated by investors.

The Last 25 Years

The Japanese economy has been fighting weak growth and deflationary forces for over 25 years. Japan’s equity market and real estate bubbles burst in the first week of 1990, presaging deflation and stagnant economic growth ever since. Despite countless monetary and fiscal efforts to combat these economic ailments, nothing seems to work.

Any economist worth his salt has multiple reasons for the depth and breadth of these issues but very few get to the heart of the problem. The typical analysis suggests that weak growth in Japan is primarily being caused by weak demand. Over the last 25 years, insufficient demand, or a lack of consumption, has been addressed by increasingly incentivizing the population and the government to consume more by taking on additional debt. That incentive is produced via lower interest rates. If demand really is the problem, however, then some version of these policies should have worked, but to date they have not.

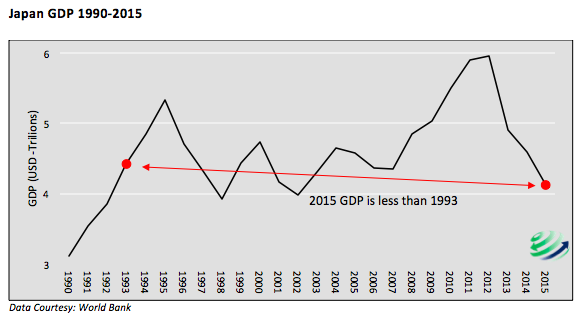

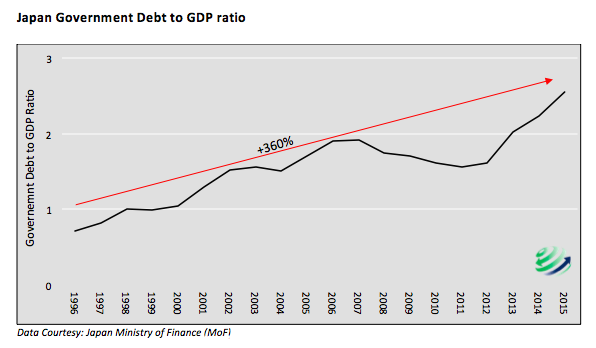

If the real problem, however, is too much debt, which at 255% of Japan’s GDP seems a reasonable assumption to us, then the misdiagnosis and resulting ill-designed policy response leads to even slower growth, more persistent deflationary pressures and exacerbates the original problem. The graphs below shows that economic activity is currently at levels last seen in 1993, yet the level of debt has risen 360% since 1996. The charts provide evidence that Japan’s crippling level of debt is not helping the economy recover and in fact is creating massive headwinds.

What is so confounding about this situation is that after 25 years, one would expect Japanese leadership to eventually recognize that they are following Einstein’s definition of insanity – doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. Equally insane, leaders in the rest of the developed world are following Japan over the same economic cliff.

Throughout this period of economic stagnation and deflation, Japan has increasingly emphasized its desire to generate inflation. The ulterior motive behind such a strategy is hidden in plain sight. If the value of a currency, in this case the Yen, is eroded by rising inflation debtors are able to pay back that debt with Yen that is worth less than it used to be. For example, if Japan were somehow able to generate 4% inflation for 5 years, the compounded effect of that inflation would serve to devalue the currency by roughly 22%. Therefore, debtors (the Japanese government) could repay outstanding debt in five years at what is a 22% discount to its current value. Said more bluntly, they can essentially default on 22% of their debt.

What we know about Japan is that their debt load has long since surpassed the country’s ability to repay it in conventional terms. Given that it would allow them to erase some percentage of the value of the debt outstanding, their desperation to generate inflation should not be underestimated. One way or another, this is the reality Japan hopes to achieve.

QE

Quantitative easing (QE) is one of the primary monetary policy approaches central banks have taken since the 2008 financial crisis. With short term interest rates pegged at zero, and thus the traditional level of monetary policy at its effective limit, the U.S. Federal Reserve and many other central banks conjured new money from the printing presses and began buying sovereign debt and, in some cases mortgages, corporate bonds and even equities. This approach to increasing the money supply achieved central bank objectives of levitating stocks and other asset markets, in the hope that newly created “wealth” would trickle down. The mission has yet to produce the promised “escape velocity” for economic growth or higher inflation. The wealthy, who own most of the world’s financial assets, have seen their wealth expand rapidly. However, for most of the working population, the outcome has been economic struggle, further widening of the wealth gap and a deepening sense of discontentment.

The Nuclear Option

In 2014, as the verdict on the efficacy of QE became increasingly clear, European and Japanese central bankers went back to the drawing board. They decided that if the wealth effect of boosting financial markets would not deliver the desired consumption to drive economic growth then surely negative interest rates would do the trick. Unfortunately, the central bankers appear to have forgotten that there are both borrowers and lenders who are affected by the level of interest rates. Not only have negative interest rates failed to advance economic growth, the strategy appears to have eroded public confidence in the institution of central banking and financially damaging the balance sheets of many banks.

In recent weeks, former Federal Reserve (Fed) chairman Ben Bernanke paid a visit to Tokyo and met with a variety of Japanese leaders including Bank of Japan chairman Haruhiko Kuroda. In those meetings, Bernanke supposedly offered counsel to the Japanese about how they might, once and for all, break the deflationary shackles that enslave their economy using “helicopter money” (the term was coined by Milton Freidman and made popular in 2002 by Ben Bernanke). What Bernanke proposes, is for Japan to effectively take one of the few remaining steps toward “all-in” or the economic policy equivalent of a “nuclear option”.

The Japanese government appears to be leading the charge in the next chapter of stranger than fiction economic policy through some form of “helicopter money”. As opposed to the prior methods of QE, this new approach marries monetary policy with fiscal policy by putting printed currency into the hands of the Ministry of Finance (MOF or Japan’s Treasury department) for direct distribution through a fiscal policy program. Such a program may be infrastructure spending or it may simply be a direct deposit into the bank accounts of public citizens. Regardless of its use, the public debt would rise further.

According to the meeting notes shared with the media Bernanke recommended that the MoF issue “perpetual bonds”, or bonds which have no maturity date. The Bank of Japan (BOJ or the Japan’s Central Bank) would essentially print Yen to buy the perpetual bonds and further expand their already bloated balance sheet. The new money for those bonds would go to the MoF for distribution in some form through a fiscal policy measure. The BoJ receives the bonds, the MoF gets the newly printed money and the citizens of Japan would receive a stimulus package that will deliver inflation and a real economic recovery. Sounds like a win-win, huh?

Temporarily, yes. Economic activity will increase and inflation may rise.

Let us suppose that the decision is to distribute the newly printed currency from the sale of the perpetual bonds directly into the hands of the Japanese people. Further let us suppose every dollar of that money is spent. In such a circumstance, economic activity will pick up sharply. However, eventually the money will run out, spending falters and economic stagnation and decline will resume.

At this point, Japan has the original accumulated debt plus the new debt created through perpetual bonds and an economy that did not respond organically to this new policy measure. Naturally the familiar response from policymakers is likely to be “we just didn’t do enough”. It is then highly probable another round of helicopter money will be issued producing another short lived spurt of economic activity. As with previous policy efforts, this pattern likely repeats over and over again. Each time, however, the amount of money printed and perpetual bonds issued must be greater than the prior attempts. Otherwise, economic growth will not occur, it will, at best, only match that of the prior experience.

Eventually, due to the mountain of money going directly in to the economy, inflation will emerge. However, the greater likelihood is not that inflation emerges, but that it actually explodes resulting in a complete annihilation of the currency and the Japanese economy. In hypothetical terms as described here, the outcome would be devastating. Unlike prior methods of QE which can be halted and even reversed, helicopter money demands ever increasing amounts to achieve the desired growth and inflation. Once started, it will be very difficult to stop as economic activity would stumble.

The following paragraph came from “Part Deux – Shorting the Federal Reserve”. In the article we described how the French resorted to a helicopter money to help jump start a stagnant economy.

“With each new issue came increased trade and a stronger economy. The problem was the activity wasn’t based on anything but new money. As such, it had very little staying power and the positive benefits quickly eroded. Businesses were handcuffed. They found it hard to make any decisions in fear the currency would continue to drop in value. Prices continued to rise. Speculation and hoarding were becoming the primary drivers of the economy. “Commerce was dead; betting took its place”. With higher prices, employees were laid off as merchants struggled to cover increasing costs”.

The French money printing exercise ultimately led to economic ruin and was a leading factor fueling the French revolution.

Summary

Is it possible that Bernanke’s helicopter money approach could work and finally help Japan escape deflation in conjunction with a healthy, organically growing economy? It has a probability that is certainly greater than zero, but given the continual misdiagnosis of the core problem, namely too much debt, that probability is not much above zero. There is a far greater likelihood of a multitude of other undesirable unintended consequences.

Of all the developed countries, Japan is in the worst condition economically. Most others, including the United States, are following the same path to insanity though. Unlike Japan, other countries may have time to implement policy changes that will allow them to avoid Japan’s desperate circumstances.

To gain a more complete understanding of 720 Global’s economic thesis and the policy changes required, we recommend our prior articles “The Death of the Virtuous Cycle” and “The Fifteenth of August”.

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.