What beginning to December for the financial markets!

As fears that the world’s two largest economies would continue to escalate their trade war subsided, we began last week thinking the worst was behind us.

Our expectations were shattered last Tuesday when the S&P 500 took a nose dive, falling as much as 6% in one-and-a-half trading sessions.

Whether you are actively trading or simply observing, the past week has certainly been draining.

The last month, for that matter, feels akin to watching a ten-round fight with a young Mike Tyson (don’t think any of his early fights went ten rounds, but you get the point).

Put into perspective, these feelings of anxiety seem rather odd. Consider the fact that we are at a higher level today then we were on October 30, and that there have been more up days than down days during that time. While there are undoubtedly many contributing factors to the emotional pain, they can all be traced back to something call loss aversion.

Several weeks ago, we penned a piece titled “Decisions Under Risk,” outlining the work of Amos Treversky and Daniel Kahneman on loss aversion. They showed that we tend to make systematic mental errors as humans, giving losses a greater weight than gains in our decisions. To demonstrate this, ask yourself the following two questions.

Would you rather?

A) 95% chance of receiving $10,000 and 5% chance of receiving nothing

B) 100% chance of receiving $9,500

Would you rather?

A) 95% chance of losing $10,000 and a 5% chance of losing nothing

B) 100% chance of losing $9,500

Most people select B for the first question and A for the second, despite the odds and expected outcomes being identical for both A & B in both scenarios. The only difference is how you value losses versus gains. Research has indicated that we feel the pain from losses roughly twice as much as the pleasure from an equal sized gain. This bias, which we all possess to varying degrees, can make investing a painful experience if we pay too much attention to the day-to-day, or worse, the minute-by-minute gyrations in the market.

Reduce the pain and enjoy the gains

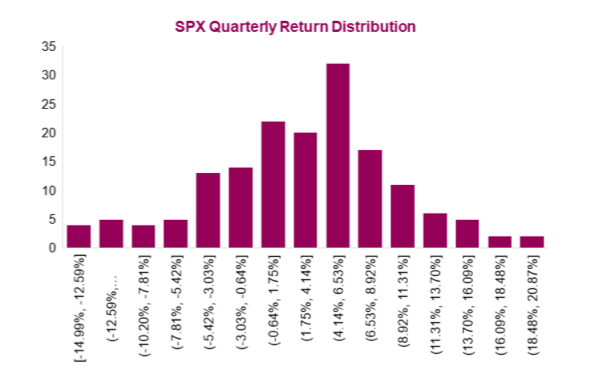

Looking back at the past forty years, the annualized return for the S&P 500 has been 8.8% with a 16.4% error rate per annum (annualized standard deviation). It has been a good experience over the past four decades for S&P 500 investors, who would have doubled their money every eight years or so. Most investors would be content with those results. If we look back over the past forty years, thirty-one have been positive and only nine negative. Even though those negative years hurt roughly twice as much as the positive ones, there have been more than enough good years to make the overall experience an enjoyable one.

The problem is most people do not check their investment portfolio just once a year. We live in a connected society where clients of almost any investment firm can view their portfolio on their mobile devices, awarding them the opportunity to check their results as often as they would like.

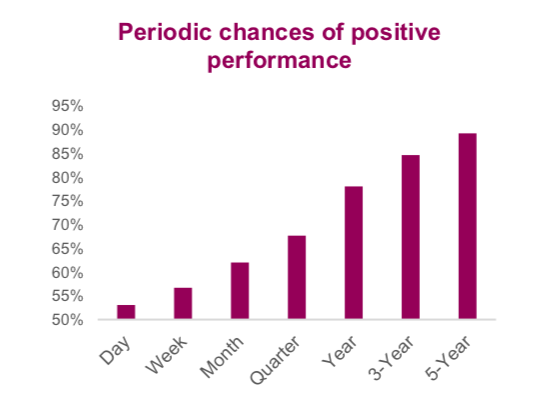

If the client, invested soly in the S&P 500, were to check their portfolio annually 78% would be positive, quarterly, roughly 68%, if they checked monthly, only 62% would be positive; daily would be 53%, positive. If you view your investment performance every day, it is pretty much a coin flip whether your portfolio will be up or down.

If a client examined her performance daily, it would be an emotionally draining experience with 11 pleasurable days versus 10 unpleasurable over a twenty-one trading day month. The investment experience would be a serious emotional deficit because as there are not enough positive outcomes to offset the negative ones. Looking at the data, the least emotionally taxing experience appears to be checking your portfolio once a quarter.

Constant examination and evaluation of investment performance can be emotionally draining and to a larger degree, irrelevant. We spend extensive time selecting and overseeing managers. We prefer to evaluate the performance of a manager over a full business cycle, to get a somewhat relevant understanding of their investment acumen.

However, the reality is that might not even be enough time to eliminate the complete randomness of past performance. It is impossible to say exactly what time frame you would need to measure to truly understand the abilities of an active manager. But the one thing we can say is that the shorter the time frame, the better the chance that the results are representative of randomness versus any type of skill. We think our choices in portfolio construction and equity selection can drive our annual performance, but we have virtually no ability or skill in trying to outperform in the next ten minutes or next few days.

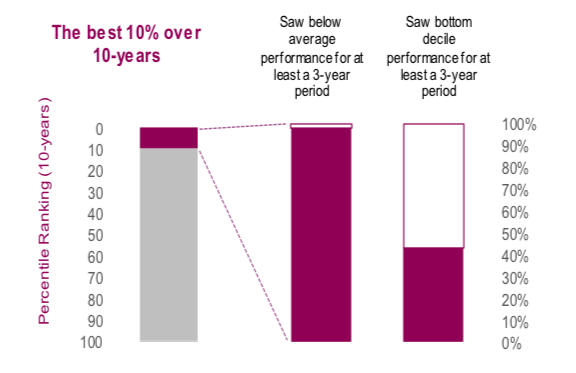

A frequent bias we find many investment professionals and clients falling victim to is recency bias, placing far too much emphasis on the most recent piece of information and not placing enough weight on the long-term picture. This was eloquently demonstrated in a Morningstar study of all U.S. equity mutual funds with a ten-year track record. Of those top performing funds, they found that over 90% spent a three- year period underperforming the category, which consists of all funds. Even more surprising was that 40% of those managers spent at least three of those ten years in the bottom decile.

The reality is that a lot of investors, likely us included, would stop using that manager after a prolonged period of bottom decile performance. Obviously, this would be the completely wrong time, because if they have a ten-year performance in the top decile, those other years on average must have been tremendous.

The lesson

Investing is a long term process that can span many decades for most investors. Most bull markets last six to eight years and bear markets one to two years. It is very important to think about your future self and not get caught up in the daily gyrations of the market. If you do not have to, it is a good idea to monitor your results a little less frequently.

Secondly, being short-sighted when evaluating the performance of your investments, investment managers or financial advisors can be very costly. Many investments tend to be mean-reverting, meaning what has worked previously, probably won’t work going forward, and what wasn’t working, very well might work in the future. It is better to assess how that stock or mutual fund will work in your forecasted future environment and not make allocations based solely on what you have observed previously.

As “The Great One” aka Wayne Gretzky said, “Skate to where the puck is going, not where it has been.”

Twitter: @ConnectedWealth

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.