The most prevalent disclaimer in the investments world goes something like this – “past performance may not be repeated”. If you don’t believe us, just read the disclaimers from investment firms, including ours.

Despite the prevalence of this disclaimer, investors often place the lion’s share of their decision making process on past performance, sometimes just recent performance. With this comes a number of dangers, not just for the investment selection process but for overall portfolio construction and diversification.

In short, performance chasing can be bad for your wealth.

While past performance should not be ignored, it should be viewed with a certain lens that goes beyond the simple numbers and brings in other factors such as an investment’s role in the portfolio and the market environment.

Performance, performance, performance

If your advisor suggests adding ABC Fund to your portfolio, the natural first question that comes to mind is ‘how has it done?’ Similarly, if a mutual fund sales person pitches a fund to an advisor, their first question is often the same. The hope is a good track record is evidence of a superior manager or one who is really doing things right. And of course, if such performance continues, it would be ideal.

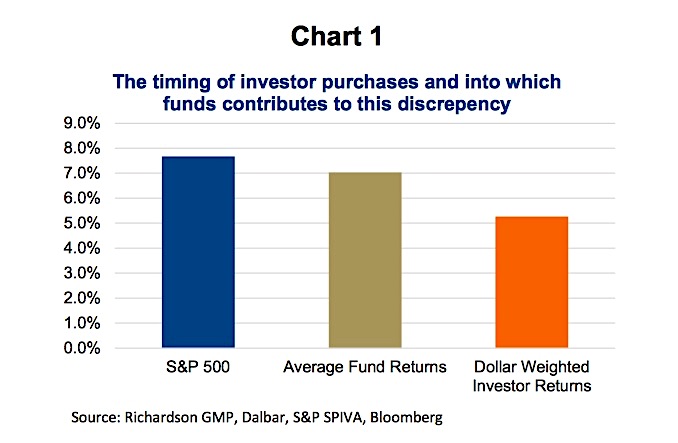

But this is often a short cut that avoids more critical thinking or analysis to understand why the fund or investment has performed well (more on this later). This behaviour obviously leads to performance chasing. A small fund, measured in the assets under management (AUM), experiences a strong performance run, after which money piles into the fund and the AUM grows substantially just when there is mean reversion in performance. Net result while the fund still has decent performance track record, the dollar weighted performance is not nearly as impressive. This is one of the reasons investor performance remains substantially below both market and average fund returns. Dalbar measures investor performance based on the timing of dollars invested to provide a more accurate depiction of what investors actually experience. This is below the market index return and below the average fund return. (Chart 1 below)

The asset management industry is well aware of the importance of performance on attracting assets. So much so that many fund companies will be incubating behind the scenes multiple funds at any given time with the minimal amount of assets and required investors. The ones that post strong performance after a period, often three years, will then be marketed to advisors and the public. The ones that didn’t perform are likely closed, as if it never happened. As an aside, we do not do this at Connected Wealth.

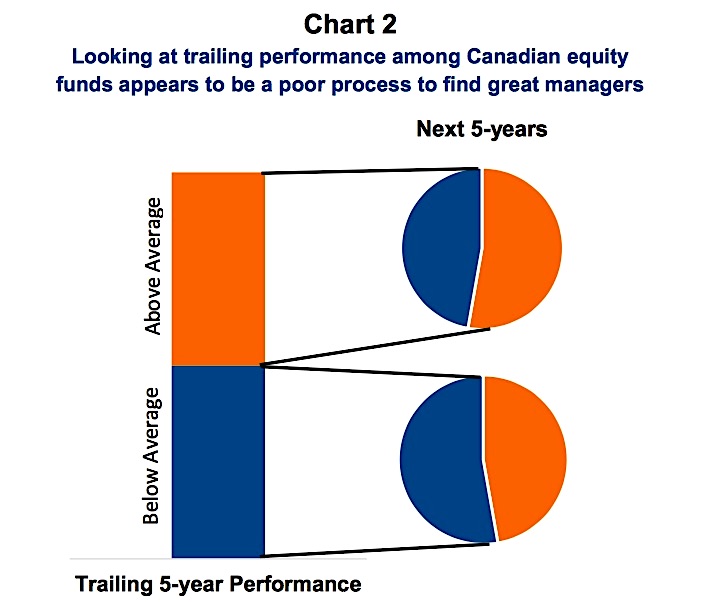

We are not suggesting performance should be ignored, but its importance is only one piece of the decision. In Chart 2, we took the five-year trailing performance a number of years back for all Canadian equity funds and broke them down into above and below average. We then analyzed how many of the above average performers remained as such for the next five years. 53% remained as outperformers, which is fairly close to 50/50. Similarly, almost half of underperformers (47%) became outperformers in the subsequent five-year period.

Another study by Cambridge Associates provided even more insight into the dangers of just looking at performance. They looked at a number of top quartile U.S. managers that were in the top quartile based on their ten-year performance history. Quite a compelling group eh? They found 98% of those managers experienced a three-year period performing below average during the ten-year analysis period. Even more impactful 43% of them experienced a three-year period in the bottom decile vs. their peers. That means this top quartile manager was in the bottom 10% for a three-year period. If one of your funds fell into the bottom decile, would you sell it? Remember, these happened to be funds that recovered and went on to be on top over the decade period.

The most important question – Why?

We suggest performance be more critically analyzed to gain insight into why the performance is either good or bad. What is driving the performance and what is more likely to drive future performance (that is key). Plus, how does an investment fit in a portfolio?

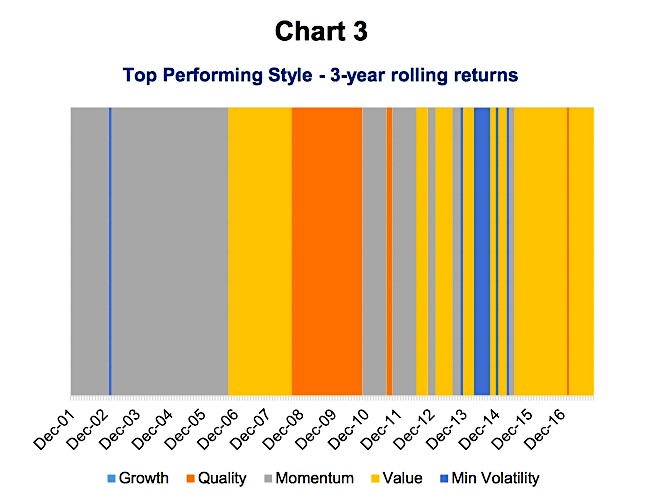

The top performing managers in the Cambridge study had strong disciplined strategies from which they did not waiver during periods where their approach was out of style. The fact is different approaches enjoy periods of success and then the market changes and the same approach may underperform. In fact, the dominant style tends to change often. Chart 3 highlights which style among Growth, Quality, Momentum, Value or Minimum Volatility outperformed on a three-year rolling basis (U.S. data, using MSCI style indices). As you can see, it changes and will change again.

What if during the period Quality dominated (orange), you adjusted your portfolio by selling other style managers and buying more Quality focused managers? Well, you would lose when Momentum came back into vogue and your portfolio was full of Quality. Today value is the winning strategy based on the trailing 3-year performance, but momentum has been dominating in 2017 thanks to gains in FAANG stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Alphabet-formerly Google). Should a Quality focused manager underperforming today’s market be sold and more money put into a more Momentum manager? Maybe, but this is herd type behaviour, chasing performance.

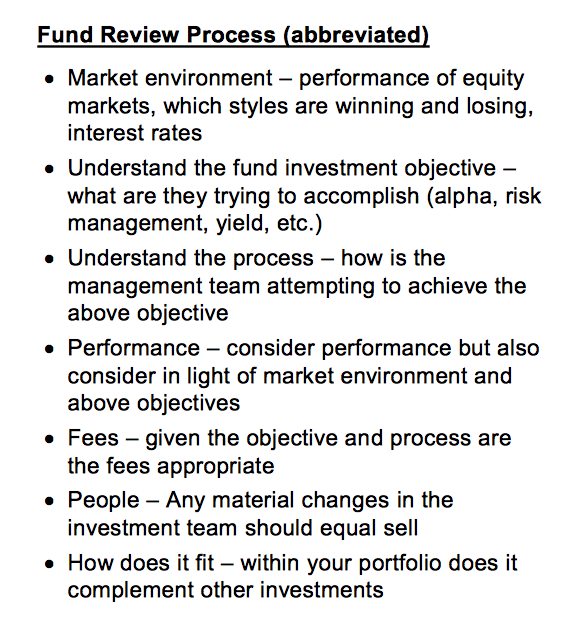

It is more important to understand the strategy, the style and the market. The key is to find quality managers in various styles to provide diversification. In a Momentum market, you want your Quality managers to underperform….if they are not they may have changed styles to chase what is hot. The last thing you want for portfolio construction. Lastly, we included a suggested bare minimum review process and we will expand on this in future reports.

Charts are sourced to Bloomberg unless otherwise noted.

Twitter: @ConnectedWealth

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.