The holy grail of investing is generating alpha, adding performance relative to an appropriate benchmark.

Portfolio managers around the world throw unimaginable resources at this quest that often proves elusive. It is all about getting an edge.

Some use deep fundamental analysis, digging into the financials to uncover mispriced companies or assets. Some use charts or macro views. A rising trend of late in the quest for alpha has been using more math, attempting to exploit anomalies in the market. Greater computer power coupled with a tremendous rise in available data from a multitude of sources has created a fertile environment for quants. As this discipline gains attention you will likely hear the words Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Neural Networks more and more often. Truly an exciting time as the portfolio manager’s tool box continues to grow.

Where does alpha come from?

If you are in the profession of finding alpha (or hiring those to find it for you), would it not make sense to think about where it comes from? For illustrative purposes, let’s play a simple game:

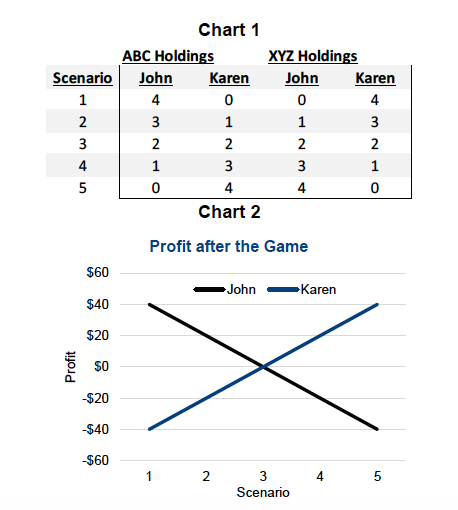

The market is comprised of only 2 companies, ABC & XYZ. At the beginning of the game, each costs $50 per share and each has four shares outstanding. There are only two investors as well, named John and Karen, and they each start with $200. Chart 1 below is the five different distributions or scenarios on how they can allocate the funds at the start of the game. Now ABC goes up to $60 and XYZ goes down to $40.

Chart 2 above is the profit distribution for each player under each scenario. If they opted for Scenario 3, they each basically owned the market and came out flat. However, if they deviated from the index (not holding equal amounts of each company in this case), someone wins and someone loses.

Now this is a very simple game but the conclusion may hold more validity than many people think. To generate alpha, you need to take it from someone else. And to do that over the long term you need an edge or advantage.

When you are Buying, Who is Selling?

If we are expected to take alpha from others, best we know with whom we are dealing. Over the years, whenever this question was raised, it often led to some confused looks. Many investors simply don’t think along these lines. They view the market more like a store. A store that sells stocks and lets you return them, albeit at always changing prices. Have you ever thought that ABC Co. has a good outlook, is improving fundamentally and, given the price, looks attractive? Then you go buy it. Well someone sold it to you and their view probably is not the same as yours. Otherwise, they would not have sold. Then again perhaps they have no view at all. So who is on the other side of trades?

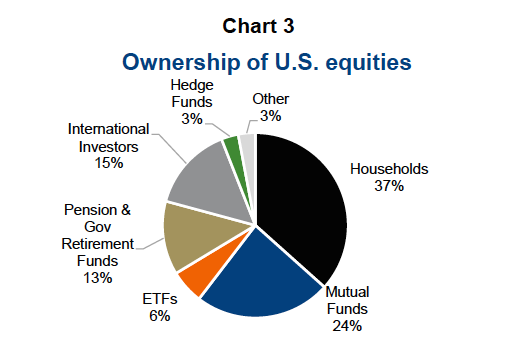

Chart 3 below breaks down the ownership of the U.S. equity market.

Ownership can be important on the motive of trading but it is more about who is trading, why and how. Let’s try and generalize traders into a few buckets, based on their approach or how they trade.

Fundamental Discretionary Traders (Active) are what many of us think of as an active participant in the market place. They could be an active fund manager, hedge fund managers, and an active manager on the international side or managing for a pension fund. They may also be a household or retail investors trading directly in equities. Whoever they are, they are fundamentally driven, active in the price discovery practice and trying to find mispriced assets to make money / alpha. Then we have the Basket Traders (Passive) who are running some sort of factor based strategy. Market cap factor ETFs are the most popular and then we have increasing assets targeting other factors as the quants rise in popularity. Most of the Passive volume is driven by flows into or out of the strategy, causing the basket of securities to be purchased or sold. As a result, there is limited consideration of price, as they are simply executing their respective basket. The final group is High Frequency Trading (HFT) and other ultra- short term algos. However, given that HFTs typically end the trading day without owning anything and are focused on shaving fractional pennies from trades, it is probably more useful to view them as a kind of transaction cost instead of a trading opponent.

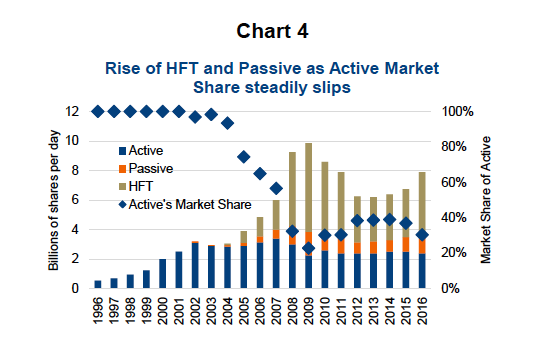

It is important to consider Active traders are trying to buy undervalued assets and sell/short overvalued assets. This is price discovery. They will make different mistakes compared to Passive traders who are not so price sensitive and instead are trading based on flows and their basket (factor) portfolio. Chart 4 provides a breakdown of trading volume based on it being an Active manager, Passive strategy or HFT. The decline of Active’s market share (and rise of Passive) may have implications on market pricing efficiency plus on where and how to find alpha in this changing environment.

Implication of Active’s Declining Market Share

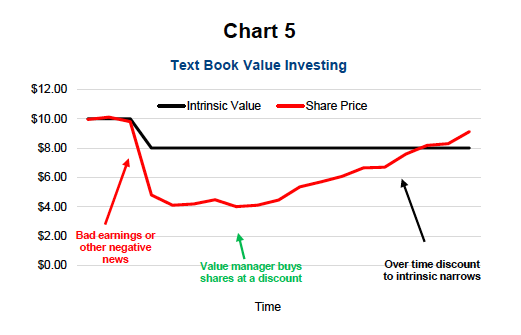

Active portfolio management is in its purest form the attempt to find mispriced assets and profit from them. In doing so this increases market efficiency and accurate pricing. Value investors look for company’s trading below their intrinsic value due to some impairment or neglect in the market. They research them, buy them and wait for the market to come around to their view and bid up the company back to its intrinsic value (Chart 5).

The narrowing of the discount to intrinsic value is predicated on other active investors coming to a similar conclusion and subsequently bidding up the share price then what if there are fewer Active managers at work in the market? Could it take 50% longer or twice as long compared to when almost all traders were active? Would this partially impair the value investing approach? Could this be why active strategies have had such a hard time beating the market over the past half-decade?

It isn’t just Value though. A growth manager believes the market is underappreciating the growth prospects of a company they own, Again, it is trading below the manager’s view of the company’s intrinsic value. They will need others to do similar work and come to similar conclusions about the rising growth prospects of the investment.

It is conceivable that the rise of more passive or basket trading will increasingly cause asset prices to be distorted. If fewer dollars are at work bidding up undervalued assets and bidding down overvalued assets, then distortions could continue to rise. And then, should we not look for alpha from different sources?

Taking Alpha – Behavioral Style

Simply put, you need an edge over other participants in the market to find mispriced assets to generate alpha. And then you need the market to agree with you and fix the mispricing (after you are either long or short of course). Value investors try and find this edge in neglected or misunderstood companies. Deep fundamental managers will dig into all financials to try and get an edge. Then there are the quants, using math and other data inputs to find a potentially mispriced asset. Growth managers finding companies that have better growth rates than the market gives them credit.

If the goal is to take alpha from ‘someone’ via a mispriced asset then would it not be logical to begin the search for alpha where investors make mistakes and contribute to the asset being mispriced? It is with this mindset that we began researching investment strategies that attempt to find instances where other investor behaviors cause assets to be mispriced.

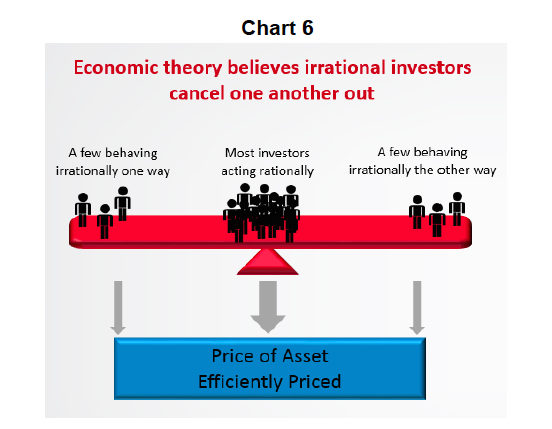

Chart 6 depicts how economic theory handles irrational investors. Believing most investors act rationally, in their best interest, with a few behaving irrationally. However economic theory believes the irrational investors are evenly distributed, canceling each other out on how they influence asset prices.

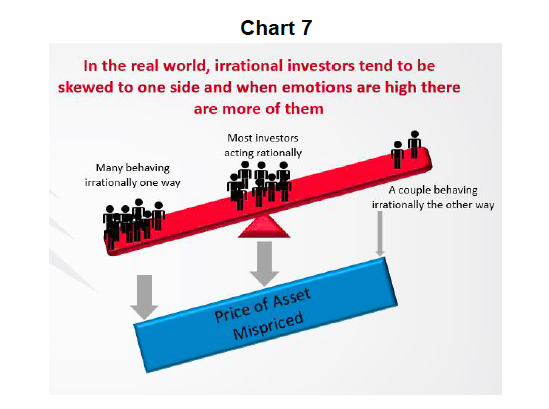

Chart 7 is likely closer to reality. There are times when more investors are irrational (think 2008) and very often the irrational investors are clustered to one side. This causes assets to be mispriced, and a potential opportunity to create alpha.

Finding instances where investors are behaving irrationally, causing an asset to be mispriced, may prove to be a long-term source of alpha. We all know investors make mistakes, both active and passive. Sometimes, this is when earnings are released, or when everyone gets on one side of a trade, or ETF flows push the price of some companies artificially higher, or a theme goes mainstream. The key is when or how the irrational investors become rational again and how that influences asset prices.

Charts are sourced to Bloomberg unless otherwise noted.

Twitter: @ConnectedWealth

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.