“All assets are priced where they are today because of central banks. That’s modern finance — it’s not about psychology or flows anymore, it’s about what the central banks are going to do next.” – Mark Spitznagel

Cause and Effect

Rene Descartes, a 17th-century mathematician, asked the fundamental question of how causal power functions. He was interested in how things relate to each other in terms of causality and how the thought of an action gets translated into a physical action. The theory he came up with, called “Interactionism,” affirms the relationship between thought and action.

Importantly for our discussion, Descartes knew that any effect must have an antecedent cause.

When we are unclear about something, Descartes teaches us to search diligently for first principles, those things about which we are certain, and then explore what might have caused an event or observed the effect.

Warnings

In recent weeks, we have heard a variety of pundits, including a parade of Federal Reserve (Fed) officials speaking about mounting risks in the credit markets. Steve Eisman, who correctly pre-identified the magnitude of the sub-prime mortgage debacle, expressed confidence in commercial banks but worried that a U.S. recession would bring “massive” losses to the corporate bond market.

The Fed published a report stating that there are meaningful risks in the corporate bond markets due to the amount of issuance that has occurred over the past decade and the weak credit quality of much of that issuance. As documented in many prior articles, we concur with those concerns and suggest the effect has a nasty way of sneaking up on central bankers. For our latest on the topic please read The Corporate Maginot Line.

The potential problems brewing in the credit markets are an effect. Corporations did not just decide to issue mountains of debt, much of which is low rated and of poor quality, for no reason at all. They did it, in large part, as a result of the economic and market environment created by the Fed through low interest rates and quantitative easing (QE).

The Fed removed over $4 trillion of the highest quality bonds out of the domestic market. In doing so, they pushed interest rates to historic lows. The combined effect all but forced investors to seek out higher-yielding, riskier instruments. As a result, the demand was ready and more than willing to absorb the on-coming wave of corporate supply and to do so at remarkably low yields and therefore very favorable terms for the issuers.

Cause

At the depths of the financial crisis, the Fed advertised QE as a means to boost asset prices, create a wealth effect, and fuel consumer borrowing and spending. It was sold as an economic growth booster that would benefit everyone. The ultimate objective was to staunch the crisis and foster an economic recovery.

Through QE, the Fed did this by acquiring mortgage and Treasury bonds from large banks and crediting those banks’ reserve accounts with digitally manufactured U.S. dollars. From September 2008 until January 2015, when the third round of QE was completed, the Fed balance sheet swelled by nearly $4 trillion while bank reserves grew from $2 billion (that’s $0.002 trillion) in July 2008 to almost $3.0 trillion.

As the Fed acquired vast amounts of high quality fixed-income securities from banks through QE, it created a vacuum in the bond market that had to be filled. The vanishing high-quality Treasuries and mortgages generated fresh demand for investments of lower-quality bonds.

Strong investor demand was met by corporations increasingly anxious to issue cheap debt to fund their activities. While those activities included capital expenditures, the debt increasingly was used to fund dividend payouts and share buybacks.

Not coincidently, while the Fed’s balance sheet was expanding by $4 trillion, corporate debt outstanding exploded from $5 trillion to well over $9 trillion.

Debt-for-equity

As mentioned, the Fed removed high-quality securities from the market enabling corporate issuers to step in to fill the resulting gap. Since QE began, nearly 30% of the new corporate debt issued was used for stock buybacks. Putting the pieces of the mosaic together, it is fair to say the most intense corporate debt-for-equity swap in recorded history was enabled by the Fed via monetary policy and the federal government through tax-cuts.

This is symptomatic of a variety of issues that have been created by prolonged extraordinary monetary policy. In the same way that corporate behavior has been seriously altered as described above, every central bank in the developed world has undertaken even more extreme measures to foster growth, dictating that the behavior of market participants transform in some manner.

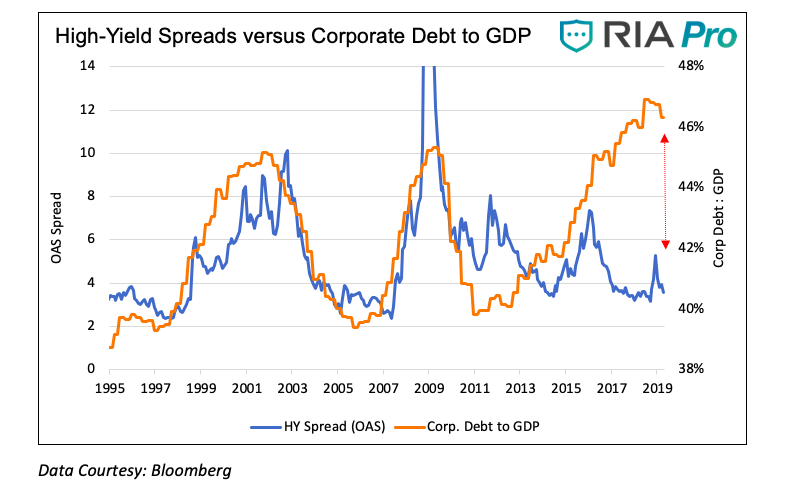

The chart below is a stark reminder of how the Fed has changed the natural order of the corporate debt market. Over the past 25 years, when corporate debt loads became onerous, investors required higher yields and wider spreads to compensate them for the added risks.

Today, despite the extreme amount of corporate leverage and the low quality of corporate credit, junk spreads remain near all-time lows. As shown below and highlighted by the red arrow, the long-standing correlation between leverage and high yield spreads is broken.

This gross distortion and many others throughout the market offer clues and compelling evidence of a “cause.” Collectively, they point to a monetary policy that is manipulating the price of money and fostering irrational behaviors.

Effect

In his book, Economics in One Lesson,Henry Hazlitt states, “…the whole of economics can be reduced to a single lesson, and that lesson can be reduced to a single sentence. The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.”

The side-effects of extraordinary monetary policy, especially those that have been left in place for a decade, have scarcely been considered by the Federal Reserve. What was great (as in “get filthy rich” great) for the banks and the wealthy was not such a hot deal for the rest of the American public. The side effects are becoming more apparent and serious every day. As an aside, the rolling wave of populism did not emerge unprompted. It too is an effect. As Deep Throat said to Woodward and Bernstein, “Follow the money.”

Instead of investing in new property, plant, equipment, innovation, and employee training for the long-term benefit of their shareholders, employees, and the communities in which they operate, companies instead are taking advantage of ultra-low funding costs to buy back expensive stock. In a desire to prop up stock prices to enhance their compensation and satisfy short term investors, corporate executives have and continue to make poor capital allocation choices.

If the goal was to increase shareholder value via a temporarily higher share price, then corporations succeeded, albeit temporarily. The goal always should be to increase long-term shareholder value via stronger growth; a goal corporations have largely ignored.

After ten years of poor decision making, many companies are left with inflated stock prices but dim prospects for future growth to fund their obese debt structures.

Summary

A weak post-crisis economic recovery that hurt low income wage earners alongside monetary policy that fueled steady gains in the cost of living meant many people were going to be left behind. The calculus did not anticipate that effect would extend so far up into the middle class. Struggling to maintain their previous standard of living, consumers borrow at the Fed’s new cheap rates. Quoting from the book, The Big Short, “If you want to make poor people feel rich, give them cheap loans.”

That is exactly what the Fed did after the financial crisis for more than a decade and counting. That game has an unhappy effect as the economy loses productive capacity and has little fuel to spur organic growth and wage gains.

The series of events playing out right before us, like a pre-release movie trailer, reveals teasing fragments of information. The corporate debt market is today’s teaser. The set-up for that was the Fed-induced debt-for-equity swap. To anyone willing to pay attention to the data, it is again plain to see the excesses brewing in today’s environment which is eerily similar to those of 2005 and 2006. Even Dallas Fed President Kaplan has raised a warning flag by highlighting the amount and poor quality of corporate debt which could add to the burden on the economy in a downturn. He diplomatically understates the problem but at least he acknowledges it.

Monetary policies of the Fed are the cause. Those policies enable imprudent deficit-spending and accumulation of leverage at ultra-low interest rates.

Debt loads in the government, corporate and household sector, and various other hidden imbalances are the effect. What we know about circumstances is a concern, but what should be especially troubling are those things of which we are not even yet aware.

Turning back to Descartes, he offers this wisdom: “The senses deceive from time to time, and it is prudent never to trust wholly those who have deceived us even once.”

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.