Last week when the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) met, market participants were divided as to whether or not the Federal Reserve would raise interest rates. Most economists expected a hike, as did the short end of the yield curve; two-year Treasury yields had shot up to 0.82 percent into the meeting. But Fed funds futures, on the other hand, were pricing in low odds of an interest rate hike.

Even among FOMC members, the difference in opinion was stark.

One reason for this dichotomy is the prevailing wide divergence in economic data. Those particularly focused on consumer inflation were rooting for the status quo to continue. Those looking at the unemployment rate, however, were expecting a Fed tightening cycle to begin.

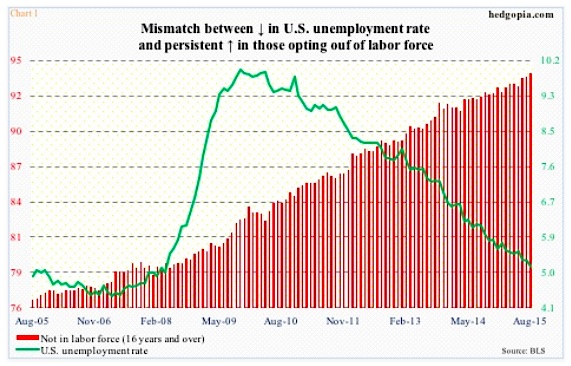

Even within employment, the dovish camp could cite the large number of Americans not in the labor force as a reason not to hike interest rates, while the hawks could point to a tightening labor market, which was evident in the persistently declining unemployment rate (see chart 1 below).

Not In Labor Force vs Unemployment Rate

There will be a rate hike at some point, as interest rates cannot go any lower (unless they go negative). This is not up for debate. The only question is when. What is probably not up for debate is this:

Unlike in the past when once a tightening cycle begins, it persists for a while – both magnitude and duration – this one has the potential to be a shallow one.

The most common arguments for this include an economy that continues to act tentative. Not to mention the fact that emerging economies/markets look vulnerable to rate shocks. But there is an even stronger case for a shallow Fed tightening cycle.

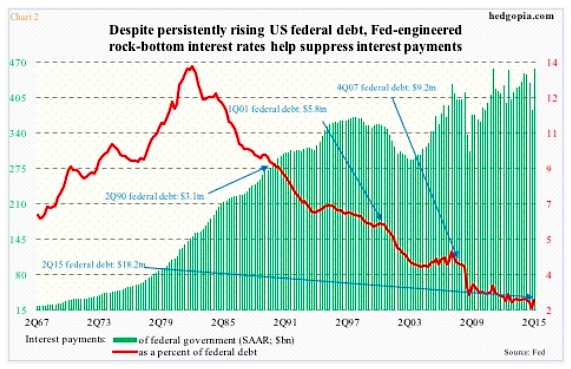

In Chart 2 below, the green bars represent the federal government’s interest payments. Back in 4Q08, even as the fed funds rate was pushed down to near zero, interest payments were less than $336 billion (at a seasonally adjusted annual rate). Seven years on, zero interest-rate policy (ZIRP) is still in place, but interest payments rose to north of $457 billion in 2Q15.

What gives? Debt is the simple answer.

The red line in chart 2 (above) represents interest payments as a percent of federal debt. It has been under pressure since the early ‘80s. That was when U.S. interest rates peaked. In 2Q82, interest payments made up 14 percent, and federal debt stood at $1.1 trillion; in 1Q15, the former dropped to 2.1 percent, even as the latter soared to $18.2 trillion. Since 2Q90, there have been three recessions; federal debt has grown six-fold since.

continue reading on next page…