What he described in the book, and his later testimony, became known as Triffin’s Paradox. Events have played out largely as he envisioned it. Essentially, he argued that reserve status affords a good percentage of global trade to occur in U.S. dollars. For this to occur the U.S. must supply the world with U.S. dollars. In other words, to supply the world with dollars, the United States would always have to run a trade deficit whereby the dollar amount of imports exceeds the dollar amount of exports. Running persistent deficits, the United States would become a debtor nation.

The fact that other countries need to hold U.S. dollars as reserves tends to offset the effects of consistent deficits and keeps the dollar stronger than it would have been otherwise.

The arrangement is as follows: Foreign nations accumulate and spend dollars through trade. To manage their economies with minimal financial shocks, they must keep excess dollars on hand. These excess dollars, known as excess reserves, are invested primarily in U.S. denominated investments ranging from bank deposits to U.S. Treasury securities and a wide range of other financial securities. As the global economy expanded and more trade occurred, additional dollars were required. Further, foreign dollar reserves grew and were lent back, in one form or another, to the US economy. This is akin to buying a car with a loan from the automaker. The only difference is that trade-related transactions occurred with increasing frequency, the loans are never paid back, and the deficits accumulate (Spoiler Alert – the auto dealer would have cut the purchaser off well before the debt burden became too onerous).

The world has grown dependent on this arrangement as there are benefits to all parties involved. The U.S. purchases imports with dollars lent to her by the same nations that sold the goods. Additionally, the need for foreign nations to hold dollars and invest them in the U.S. has resulted in lower U.S. interest rates, which further encourages consumption and at the same time provides relative support for the dollar. For their part, foreign nations benefited as manufacturing shifted away from the United States to their nations. As this occurred, increased demand for their products supported employment and income growth, thus raising the prosperity of their respective citizens.

While it may appear the post-Bretton Woods covenant was a win-win pact, there is a massive cost accruing to everyone involved. The U.S. is mired in economic stagnation due to overwhelming debt burdens and a reliance on record low-interest rates to further spur debt-driven consumption. The rest of the world, on the other hand, is her creditor and on the hook if and when those debts fail to be satisfied.

Thus, Triffin’s paradox simply states that with the benefits of the reserve currency also comes an inevitable tipping point or failure.

Looking Forward

The two questions that must be considered are as follows:

- When can our debts no longer be serviced?

- When will foreign nations, like the auto dealer, fear such a day and stop lending to us (e., transacting in U.S. dollars and re-cycling those into U.S. securities)?

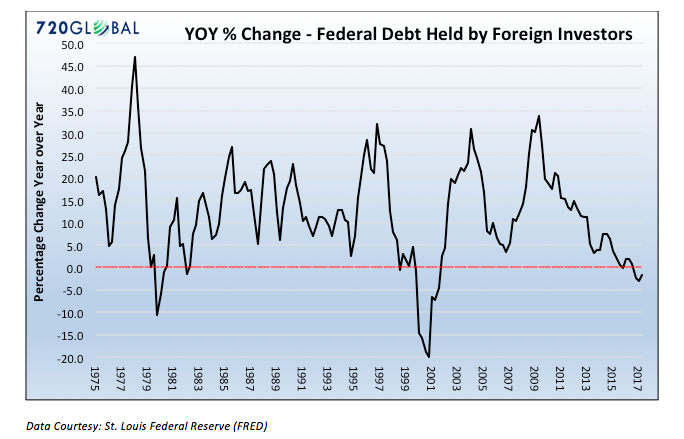

It is very likely the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 was an omen that America’s debt burden is unsustainable. Further troubling, as shown below, foreign investors have not only stopped adding to their U.S. investments of federal debt but have recently begun reducing them. This puts additional pressure on the Federal Reserve to make up for this funding gap.

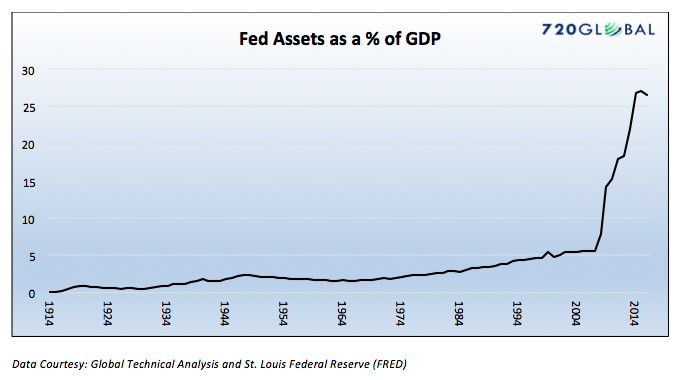

Assuming these trends continue, America must contend with an ever growing debt balance that must be serviced. In our opinion, there are two likely end scenarios. Either the resolution of debt imbalances occurs naturally via default on some debt and paying down of other debts or the Federal Reserve continues to “print” the digital dollars required to make up for the lack of funds the debt servicing and repayment requires. Given the Fed has already printed approximately $4 trillion to arrest the slight deleveraging that occurred in 2008, it does not take much imagination to expect this to be their modus operandi in the future. The following graph helps put the scale of money printing in proper historical context.

Summary

In a 2013 interview, Yanis Varoufakis, economist, academic and the Greek Minister of Finance during the most recent Greek debt crisis, mentioned a manuscript that he had recently read. The document, written in 1974 by Paul Volcker was directed to his then-boss, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Volcker stated that the U.S. need not manage its deficit as would be typical. Instead, he opined that it is our job to manage the surplus of other countries.

America’s ability to run deficits and accumulate massive debt balances for over 40 years, while maintaining its role as the global reserve currency, is a testimony to the power of our politicians and central bankers to “manage the surplus of other countries.” The questions to consider are:

- How much longer can the United States manage this tall and growing task?

- What is the tolerance of foreign holders of U.S. dollars in the face of dollar devaluation?

- Is the post-financial crisis “calm” the result of a durable solution or a temporary façade?

If in fact 2008 was a first tremor and signal of the end of this arrangement, then we are in the eye of the storm and future disruptions promise to be more significant and game-changing.

This concept has far-reaching implications well beyond economics and investing. I intend to provide future articles to extend the analysis on this topic and shed further light on how and when Triffin’s paradox may climax. I will also offer ideas on investment strategies to protect and grow wealth during what may be tumultuous times ahead.

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.