Clarity or Confusion

“Are you kidding? Are you kidding? No one knows what you’re doing.” – Economist John Taylor in response to William Dudley’s (President Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Vice Chairman of the Federal Open Market Committee) comment that the Federal Reserve (Fed) has been very clear in their discussions about monetary policy.

For the last few years the Federal Reserve has repeatedly emphasized that they want to be as open and transparent about monetary policy actions as possible. Amid those reassurances, amateur and professional Fed watchers continue to be flummoxed by the vagaries of language used in speeches, lack of adherence to implied actions and outright contradictions between their words and deeds. As evidenced by the opening quote, one wonders whether they are being intentionally delusory or whether their hubris makes them genuinely oblivious to their own obfuscations.

Confusion

In 2012, the Federal Reserve published a Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy (LINK). That statement has been updated each January since. The opening sentence of that statement contains an interesting modification to its “dual” mandate:

“The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is firmly committed to fulfilling its statutory mandate from the Congress of promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.”

While maximizing employment and engineering stable prices are the official congressionally mandated objectives, the term “moderate long-term interest rates” has never been a part of the congressional mandate. Needless to say, this is confusing and erroneous.

Ironically, with regard to its intent to explain monetary policy decisions as clearly as possible, the statement continues:

“Such clarity facilitates well-informed decision-making by households and businesses, reduces economic and financial uncertainty, increases the effectiveness of monetary policy, and enhances transparency and accountability, which are essential in a democratic society.”

So following the erroneous statement in the opening regarding their mandate, they then provide a lecture on the importance of Fed clarity to our democratic society.

Furthermore, the document is mislabeled as it contains nothing on Federal Reserve monetary policy strategy. The statement only discusses goals presented in an obtuse fashion based on their congressional mandate which they confounded in the first sentence. As for Federal Reserve monetary policy strategy (and to emphasize the point) the document conveys nothing coherent about the reaction function of the policy-setting body under scenarios where deviations from the goals emerge.

The members of the Fed have gone to great lengths in countless speeches, congressional testimonies and press conferences to portray a decision-making body that is disciplined and rigorous. Further, they incessantly attempt to set the record straight about their positive contribution to prior periods of economic and financial instability. In their view, they have never been complicit in creating economic malaise and always play the role of the good physician coming to the aid of the country in troubling economic periods. As demonstrated via the confusion mentioned above, their perspective is inconsistent and deceptive.

To offer an illustration of such inconsistencies:

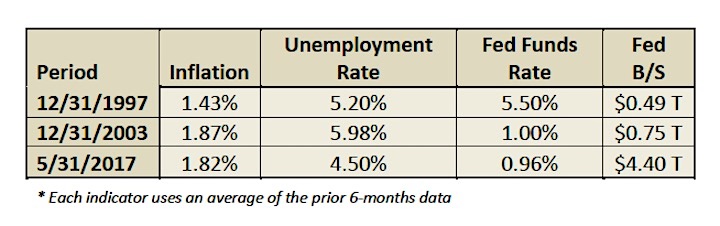

At the end of 1997, the 6-month average rate of inflation as measured by the Core PCE deflator (the Fed’s preferred inflation measure) was 1.43%, the average unemployment rate was 5.2% and the average Fed Funds rate was 5.50%.

At the end of 2003, the 6-month average rate of inflation (Core PCE) was 1.87%, the average unemployment rate was 5.98% and the average Fed Funds rate was 1.0%.

While there are a variety of other considerations for the economy when analyzing the two periods, data related to the two mandated objectives of the Fed were similar and trending in the “right” direction (inflation up, unemployment down). Despite those facts, the Fed Funds interest rate differential between the two periods, 4.50%, is enormous. Contrary to the insistence of the Fed, there is substantial evidence that the long period of low interest rate policy followed by well-telegraphed quarter-point interest rate hikes preceding the financial crisis of 2008 were major factors in generating the instabilities that almost bankrupted the financial sector.

Now, consider conditions today. The average rate of inflation (Core PCE) for the last 6-months is 1.82%, the average unemployment rate is 4.50% and the Fed Funds rate was just increased to 1.00% following 7 years at essentially 0.00%. Taking into account the size of the Fed’s balance sheet ($4.4 trillion) due to quantitative easing, the level of Fed-provided accommodation remains extraordinary even when compared to the aggressively easy monetary policy of the early 2000’s.

The argument for a more normal policy stance is stronger today than it was in either of the two prior instances, and yet the Fed’s stance is stubbornly and unjustifiably extreme.

In fairness, no two time periods are the same and policy responses are never identical. However, if the intent of monetary policy actions are aimed at ensuring the health of the economy, then it is also plausible and logical that policy, improperly applied may produce sick and unstable conditions. Interestingly, that fact is freely acknowledged by current Fed members with regard to monetary policy of the 1970’s and the Great Depression era. Why then, are the increasingly aggressive and interventionist policies of the last 20 years not a concern or even considered a factor in causing the recent boom-bust cycles by those very same Fed members? Even more importantly, why does the market acquiesce and encourage what are certain to be revealed as major policy errors? The good news is that a lot of money can be made by investors who properly identify central banker mistakes.

Summary

Current Fed policy is grossly inconsistent with the actions they have taken in the past and the rules they themselves have discussed in post-crisis years. Evidence of that fact abounds. There is an acute lack of clarity about the strategy for policy normalization, specifics about what dictates their decision-making and how they will go about it. In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, Paul Volcker was so clear about his policy objectives that he rarely needed to discuss them when he made public comments. Despite the difficulties associated with extracting the country from prior bad monetary policy, everyone knew his intent was to conquer run-away inflation and restore healthy economic growth.

Given the data comparison above and their mandate, there are sound reasons for the Fed to be much more aggressive in raising the Fed Funds rate and reducing the size of their balance sheet. The truth is they are concerned that such “hawkish” actions might greatly reduce the prices of many financial assets. Despite the short-term pain, acknowledging that current eye-watering valuations of many assets are predicated on Fed policy and not fundamentals would seem to be a prudent first step toward “normalization”. Watching the Fed Chairman evade direct answers on the topics of bubbles and policy normalization leaves no doubt that confusion, not clarity, will continue to be the Fed’s tool of choice.

“The Unseen”, is my subscription-based publication that is similar to what has been offered at no cost for the past year and a half. Go to 720Global for more details. Thanks for reading.

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.