By Allan Millar Having looked at some of the issues surrounding the Equity Risk Premium, I would also like to briefly consider the impact of behavioral economics. Damodaran (2011) investigated the possibility that there may be a behavioral or irrational element to the Equity Risk Premium (ERP). One of the theories he considered was Narrow Framing. To understand this, we must first look at conventional portfolio theory. Tobin (1958) and Markowitz (1959) preceded Sharpe (1964), the latter saying (p.426) “the process of investment choice can be broken down into two phases: first, the choice of a unique optimum combination of risky assets; and second, a separate choice concerning the allocation of funds between such a combination and a single riskless asset.” Damodaran (2011), building on Barberis, Huang and Santos (2001) goes on to say that Behavioral economists suggest that this is not the case and new investment opportunities are often considered in isolation; often times, little thought is given to the overall portfolio context, therefore leading the investor to overestimate the risk. Benartzi and Thaler (1995) suggested that this narrow framing leads investors to overestimate equity risk. Benartzi and Thaler discuss the historical ERP and (p.73) ask “why is the equity premium so large or why is anyone willing to hold bonds?” The answer they propose is rooted in psychological decision making. The first behavioral economics concept is loss aversion; this suggests that individuals are much more sensitive to sustaining losses than they are to making gains. McQueen and Vorlink (2004 p.917) added that “investors who are away from their customary level of wealth …. not only become more or less risk averse, but also …. more sensitive to news.”

By Allan Millar Having looked at some of the issues surrounding the Equity Risk Premium, I would also like to briefly consider the impact of behavioral economics. Damodaran (2011) investigated the possibility that there may be a behavioral or irrational element to the Equity Risk Premium (ERP). One of the theories he considered was Narrow Framing. To understand this, we must first look at conventional portfolio theory. Tobin (1958) and Markowitz (1959) preceded Sharpe (1964), the latter saying (p.426) “the process of investment choice can be broken down into two phases: first, the choice of a unique optimum combination of risky assets; and second, a separate choice concerning the allocation of funds between such a combination and a single riskless asset.” Damodaran (2011), building on Barberis, Huang and Santos (2001) goes on to say that Behavioral economists suggest that this is not the case and new investment opportunities are often considered in isolation; often times, little thought is given to the overall portfolio context, therefore leading the investor to overestimate the risk. Benartzi and Thaler (1995) suggested that this narrow framing leads investors to overestimate equity risk. Benartzi and Thaler discuss the historical ERP and (p.73) ask “why is the equity premium so large or why is anyone willing to hold bonds?” The answer they propose is rooted in psychological decision making. The first behavioral economics concept is loss aversion; this suggests that individuals are much more sensitive to sustaining losses than they are to making gains. McQueen and Vorlink (2004 p.917) added that “investors who are away from their customary level of wealth …. not only become more or less risk averse, but also …. more sensitive to news.”

The second behavioral economics concept is (Benartzi and Thaler, 1995 p.74) “mental accounting,” the method that, in our case, investors use to evaluate the outcomes of financial decisions. A discussion of utility theory is not here but as a brief introduction, it is concerned with choices that people make, choices which are constrained by price and income. In an investment context, it measures an investor’s preference for wealth and the amount of risk that they would consider in order to increase that wealth. Kahneman (2011 p.279) effectively describes this as “the comparison of two states of wealth”. For a relevant example we should consider an individual investor who is given two alternatives; he can invest in equities which will return an expected 12% per year, with a standard deviation of 20%. Alternatively, he may invest his capital in gilts which will return 1.5% per year. If we are looking at a short timescale, the investor is most likely to invest in Gilts. However, as the time period lengthens, the first option becomes more attractive, as long as the investment is not reviewed on a regular basis, as this may produce loss aversion. Benartzi and Thaler (1995) thus conclude that investors may not invest in equities because of their inherent loss aversion and a short evaluation period, which they name (p.74) “myopic loss aversion.’’ This is behavioral economics in motion.

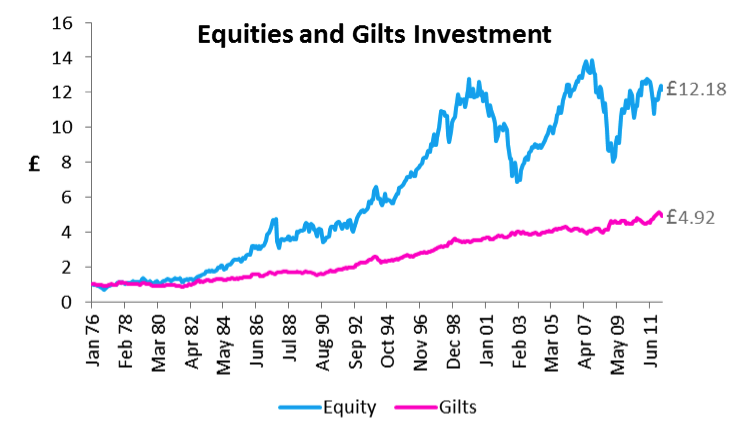

Understanding this, we deduce that the ERP is produced by loss aversion and the investors’ inability to hold the equities for a sufficient period of time as they are sold as soon as a regular review highlights any loss of value. In these articles, due to data constraints, we are looking at a short time period, 1976 to 2012. As we can see in Figure 1, to maximise the return from equities, time is a key factor:

Figure 1: Equities v Gilts 1965 to 2011 (Source: Thomson Datastream)

The difference between holding the equities and bonds for this period shown is clearly illustrated. Benartzi and Thaler (1995), conclude that they may have provided an answer to Mehra and Prescott’s ERP puzzle. Mehra and Prescott estimated the historical ERP to be around 6%, leading them to conclude that investors would need exceptionally high risk-aversion coefficients to demand these premiums. This they paraphrased (p.73) as “the annual real return on stocks has been about 7 per cent, while the real return on treasury bills has been less than 1 per cent”. Note, again, the inconsistency in even agreeing what the historical ERP is. To continue, why then has there been an aversion to taking this risk? As we have read, the answer may well be myopic loss aversion. Benartzi and Thaler (1995) also make the interesting point but they have referenced an individual investor. Would this theory also apply to an institutional investor, such as a Pension Fund? They argue that it would and the reasoning is that although the Fund probably has a fairly long existence in front of it, the individuals making the decisions won’t and will be burdened by regular reviews. They quote Leibowitz and Langetieg (1989 p.14). “Most investors and investment managers set personal investment goals that must be achieved in time frames of 3 to 5 years.” Benartzi and Thaler state that the usual equity to bond mix is 60:40, which is explained by this time-frame. John Authers and Kate Burgess in the Financial Times provided an example of this; “Allianz, with a total of about €1.7tn under management, has only 6 per cent of its insurance portfolio in equities, while 90 per cent is in bonds. A decade ago, 20 per cent was in equities.” The authors point to two reasons for this, two stock market crashes since 2000 and regulatory pressure to withdraw from stocks.

Kahneman (2011) takes this further by introducing the concept of Prospect Theory, which derived from an article about the utility of money which asked scholars to make choices about gambles where the stakes were very small. From this, Kahneman and his colleague, Amos Tversky, establish that utility theory as described above did not adequately explain attitudes to gains and losses. Kahneman (2011 p.279) states that “the dis-utility of losing $500 could be greater than the utility of winning the same amount….” This has implications for investors, especially considering their portfolio mix. To paraphrase an example: an investor may consider a choice where there is a minimum return of $900 but a 90% opportunity to accrue $1,000. Alternatively, he is faced with a second choice; where there is the possibility of losing $900 for sure, or a 90% chance to lose $1,000. In the first instance, most people are risk averse. As Kahneman points out, in the first choice (p.280) “the subjective value of a gain of $900 is certainly more than 90% of the value of a gain of $1,000.” In the second choice however, most people take the gamble. The definite loss of $900 is very aversive, driving the decision to take the gamble. This behavioral economics concept is represented in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Prospect Theory (Source www.investopedia.com)

To put this into the context of the Equity Risk Premium, it is worthwhile to adapt an example from Kahneman. In the first instance you have been given $1,000 and may choose to take an additional $500 or a 50% chance to win $1,000. The second scenario is that you have been given $2,000 and may either take a certain $500 loss or take a 50% chance to lose $1,000. Kahneman points out that people take the sure thing and the gamble respectively. In both cases, the individuals would, in the worst case, be richer by $1,500. The key factor is the reference point, $1,000 in the first case and $2,000 in the second. This loss aversion explains why people choose to invest in Gilts as opposed to Equities and if they invest in Equities, demand a premium. As we saw earlier in this article, favorable opportunities in the long-term, such as equity investment, will be missed due to this concept. Essentially, if the theory about utility of wealth was the most important factor, the individual in the example above would make the same choice in both occasions; however the reference point changes this. As Kahneman (2011 p. 279) points out defining “outcomes as gains and losses, not as states of wealth” is very important in understanding the psychology of investing.

Behavioral economics has a role to play in the ERP and it is open to debate as to its significance. The evidence does point to it being influential but we must also remember that there are regulatory pressures and institutional investors need to meet expected outflows. As we saw earlier, this leads to fewer equity investments. In my next article, we will look at the Equity Risk Premium in some detail for the period 1976 to 2012, using data from the FTSE All Share Index and UK Government Bonds.

References

- Barberis, N, Huang, M, & Santos, T 2001, ‘Prospect theory and asset prices‘, Quarterly Journal Of Economics, Vol 116 Issue 1 p. 1-53

- Benartzi, S; Thaler, R.H. Myopic loss aversion and the equity premium puzzle Quarterly Journal of Economics, Feb95, Vol. 110 Issue 1, p73-92

- Damodaran, A. (2011) Equity Risk Premiums (ERP): Determinants, Estimation and Implications – The 2011 Edition Stern School of Business

- Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, fast and slow Allen Lane Penguin Group London

- Leibowitz, M.L., and T.C. Langeteig. “Shortfall Risks and the Asset Allocation Decision.” Journal of Portfolio management, Fall 1989.

- Markowitz, H.M. (1969) Portfolio Selection, Efficient Diversification of Investments John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York

- McQueen, G, & Vorkink, K 2004, ‘Whence GARCH? A Preference-Based Explanation for Conditional Volatility’, Review Of Financial Studies, 17, 4, p. 915-949

- Mehra, R. and Edward C.P. 1985, The Equity Premium: A Puzzle, Journal of Monetary Economics, v15, p145–61.

- Tobin, J.1958 “Liquidity Preference as Behavior Towards Risk,” The Review of Economic Studies XXV p65-86.

- Sharpe, W.F. 1964, “CAPITAL ASSET PRICES: A THEORY OF MARKETEQUILIBRIUM UNDER CONDITIONS OF RISK” The Journal of Finance Vol. 19 Issue 3 p425-442

- www.ft.com John Authers and Kate Burgess “Markets: Out of Stock” | First accessed 23rd May 2012

Twitter: @MillarAllan @seeitmarket

No position in any of the mentioned securities at the time of publication.

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.