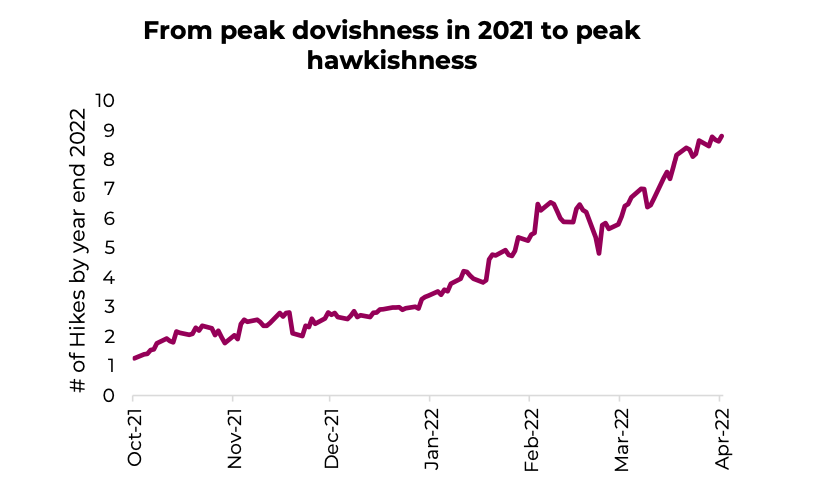

On January 1, the rate markets were pricing in Fed Funds of 0.8% for the end of 2022 — about three 25 bp rate hikes over the year.

Fast forward to today, and the futures now price in a 2.5% rate by the same year-end point, three times as many hikes in three-quarters of the time period.

Given there are six meetings left this year, that means a few hikes will have to be ‘twofers’ to hit that target. We have not seen one of those in the hiking direction since May 2000 — coincidentally around the end of the tech bubble (don’t worry, this isn’t that).

The Federal Reserve has also announced a trillion dollars of bond selling (quantitative tightening) over the next year. Most of us armchair monetary policy makers would probably agree that central banks left overnight policy rates too low and remained active with quantitative bond buying (QE) for too long. Or more simply, that they remained uber dovish for too long as economic growth recovered and inflation pressures intensified.

This comfort in remaining dovish was well founded given longer-term inflation expectations and near-term market pricing. This has been changing this year, and the pivot from dovish to hawkish, which has really just begun, is clearly warranted. But the market might be already getting a bit carried away with the degree of hawkishness, which is not an uncommon occurrence. Our job is both to determine the path, and whether or not the market is behind or ahead of that path.

Are we suggesting ignoring what central bankers are telling us with their speeches and little dots? Not at all. We always hear the saying “don’t fight the Fed”, albeit usually as they are cutting rates. We also won’t dismiss the fact that the market is tightening financial conditions in response to those speeches and dots, even before the Fed acts.

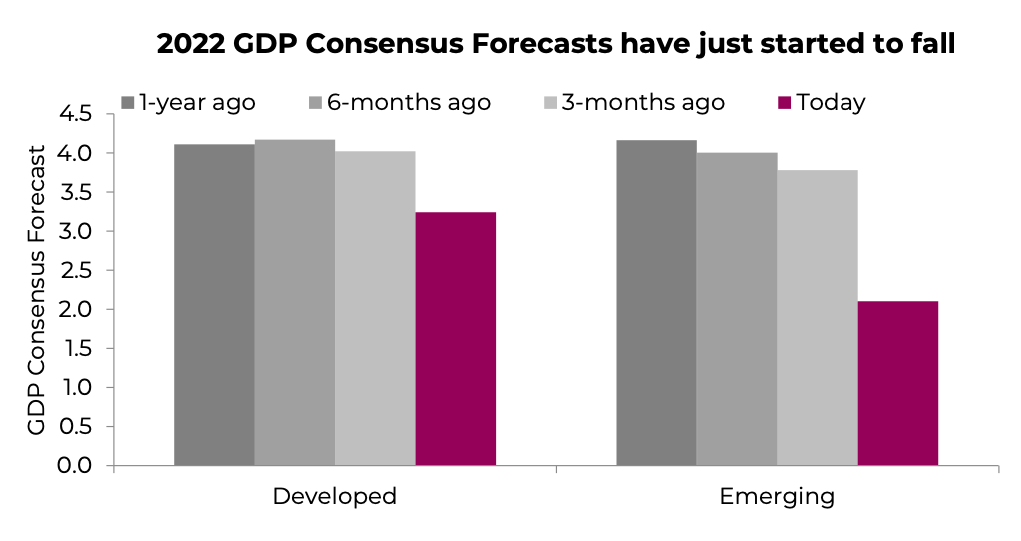

Yes, inflation continues to be a big issue. And while the impact of the Covid supply disruptions might be starting to fade, we now have conflict-related inflation pressures to absorb, and labour inflation to monitor. Central bank policy cannot alleviate supply issues, although reducing economic growth helps inflationary pressures by reducing demand. And the headwinds for economic growth are mounting:

- Oil prices – It is estimated that a $10 dollar change in the price of oil creates a 0.1% drag on global GDP growth. Oil averaged $70 in 2021, using the Brent contract. So far this year, it has averaged $100, which is also the current price. If that is an 0.3% drag on global GDP, it’s not great but not devastating given current forecasts of around 4.0%.

- China – While challenging to get an accurate gauge on economic activity, China continues to feel the impact of Evergrande within its real estate market. Although clearly not scientific, we monitor a basket of developers listed in Hong Kong or China as our indicator of the health of the industry, which suggests things are not getting worse but not improving either. Recently, import and export trade values have declined sharply, as have iron ore and coal exports from Australia. Data tends to be a bit wonky this time of year, but it’s still noteworthy. Lastly, we note as a wildcard recent Covid-related lockdowns in Shanghai.

- Europe – The war and associated economic disruptions may tip Europe into negative economic growth. Over the past few months, 2022 consensus growth has fallen from 4.2% to 3.0%. Slowing European markets is also not good for China, as trade between the two is significant.

- Yields – Much commentary focuses on what central banks are up to with the overnight rate but longer yields probably matter more, especially as it relates to mortgages. They have certainly been rising. Nominal yields are easy enough to notice, with 10-year yields in Canada and the U.S. around 2.60%. Potentially more impactful though is that real yields are quickly approaching zero. The 10-year real yield in the U.S. has been deeply negative (-0.5 to -1%) since the onset of the pandemic. In mortgage-land, the benchmark 30-year rate has risen at its fastest pace ever in 2022. Those houses that appeared on the edge of affordability have moved deeply into the “can’t afford it” category.

We are not saying “recession” — as clearly outlined in our monthly Investor Strategy section ‘reports of my death are greatly exaggerated’ (read here) — but best ready yourself for an economic growth scare. And that is a good thing as it will help alleviate inflation pressures, and will allow central banks to back off the peak hawkishness path the market is now pricing in.

Investment implications

As economic growth cools, as we are already starting to see some evidence of, the demand side of the inflation equation begins to ease the pressure. This may come later this year due to Covid and now conflict supply issues, but it is likely coming, and along with it a less hawkish path for central banks. We like to ask if the current path that is priced in, perhaps has overshot the target a little.

Yields may climb further but we would continue to use this rise in yields to incrementally add some duration for those portfolios that remain low or void of duration exposure. Within equities, we will focus less on cyclicals and rotate more to defensives or equities with higher duration. Rising inflation, rising yields, hawkish central banks, high commodity prices and slowing economic growth – something’s gotta give.

Source: Charts are sourced to Bloomberg L.P., Purpose Investments Inc., and Richardson Wealth unless otherwise noted.

Twitter: @ConnectedWealth

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.