Inflation sucks. It is essentially a tax on those consuming goods or services, as things simply cost more. Even worse, it is a regressive tax, given lower income/wealth consumers tend to spend a higher portion of their income as opposed to saving and investing, where purchasing power can be protected.

Now, if you are sitting comfortably on your nest egg and not spending too much, should inflation worry you? That depends on this raging debate: whether the current spike in inflation is a blip caused by temporary demand and supply imbalance, or whether it’s the start of something longer term. If inflation runs hotter for longer, the value of that nest egg erodes in real terms—clearly a risk to any long-term financial plan.

Currently the good news is that higher prices have been predominantly found in what the Atlanta Fed calls ‘flexible priced categories’. Breaking down the categories in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) into those that are flexible and those that are sticky clearly demonstrates that the headline number is being almost completely pushed higher by the flexible categories. The good news is the prices in these categories can come back down just as quickly, supporting the “inflation is transitory” argument. In fact, many have started this descent.

A confluence of factors caused the CPI spike. The pandemic disrupted supply chains that have been increasingly run tighter over the years to reduce costs. Demand came back faster than expected and focused more on durable goods. Global spending behaviours changed quickly.

Meanwhile, supply adjustments are not as quick. Based on manufacturing survey data, it appears that the worst may be behind us. Readings are still high in many PMI survey questions, including slower delivery times, low customer inventories, and rising backlogs, but they appear to have peaked a few months ago and are moving in the right direction.

So, all clear on inflation then? Not so fast. The headline inflation should continue to come back down as supply gradually adjusts to demand, but there are now signs of wage pressures building. Wages are more dangerous as they rarely ever come back down. Not sure if you have ever tried to tell an employee they will make less next year, not a frequent conversation for anyone. Of course, some may recall the wage spiraling in the 1970s that contributed to very high levels of inflation. While wages are not a category in CPI, they feed into the cost structure of so many categories and can be a material contributor to more widespread inflation.

The signs of wage pressures are not at all alarming today, but they have been building. Atlanta Fed’s wage tracker is currently showing 3.9% growth in wages, which is high but not too concerning. But there are other signs, such as rising overtime and an increasing quit rate, that can’t be ignored. People have been quitting at a record pace—the quit rate was 3.6% in August, which is the highest pace people have voluntarily left their jobs since the data series began in 2001. Before this summer, the quit rate had never even been over 3%.

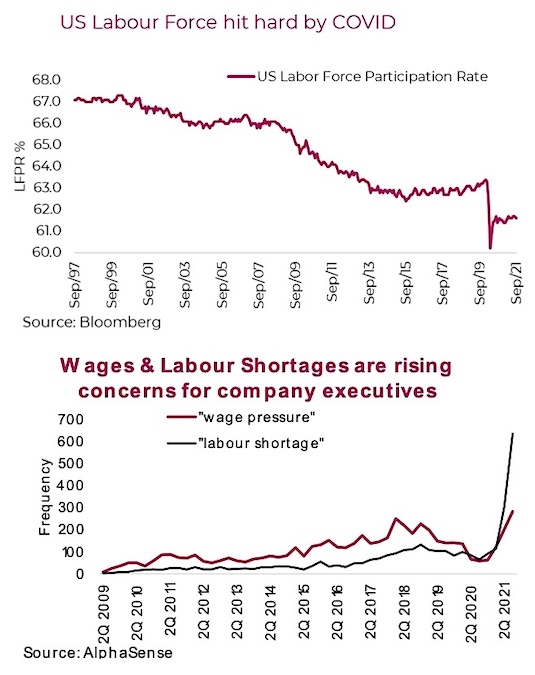

Why is this worth highlighting? Well, people rarely quit their jobs to take one with a lower or the same wage: it is more often for more money. The other indicator is the labor force participation. As measured in the U.S., the Participation Rate, which had already been in decline since peaking in 2000, took a real hit during COVID and has barely recovered.

Indications of wage pressures are also starting to increasingly show up on company earnings calls. Scanning for the frequency of executives using the phrases “wage pressure” or “labor shortage” during earnings calls shows there is mounting concern. A few industries mentioning these risks the most often over the past three months have been hotels, restaurants, commercial services (i.e., logistics companies), and banks.

More anecdotal evidence comes politically where we see increasing calls that favour labour over capital, including many regional increases in minimum wages, or corporations like Amazon announcing very public increases to their hourly rates.

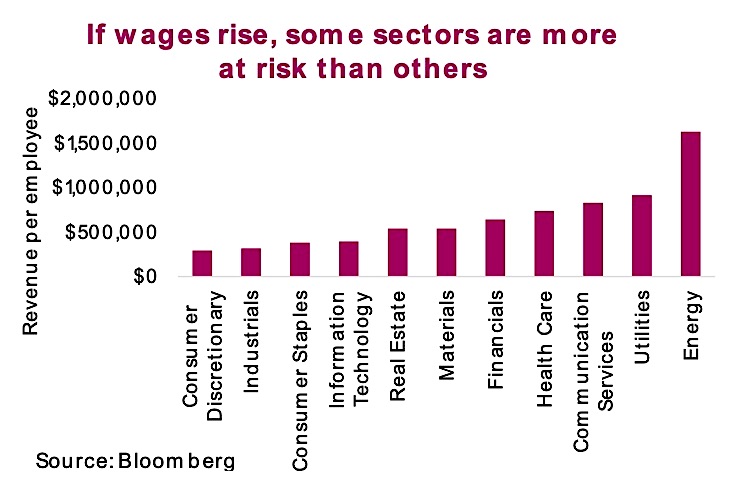

We have already seen some companies either warn or miss earnings with management attributing wages and labor as negative contributing factors, which brings up the topic of earnings sensitivity to labour.

Some companies use more capital relative to labour to generate sales. Energy, utilities, and communication services, for example, are capital intensive. This makes them less sensitive to wage pressures. Meanwhile, consumer discretionary, industrials, and consumer staples tend to use more people to generate sales, meaning the sectors are clearly more at risk. Of course, it really depends on the specific company as these sectors are rather broad and capture many sub-industries. For example, health care looks relatively safe given the sales per employee. However, while this may be the case for pharmaceutical companies, it is less so for health care service providers.

Investment Implications

The transitory argument could be applied to labour as well as it pertains to wages. The pandemic caused some jobs to disappear for over a year, other jobs were in super high demand and government jumped in to send enhanced benefits to many. Now service jobs are coming back, demand is normalizing, and benefits are fading. Given these gyrations, is it any wonder distortions in the labour market are causing wage pressures?

These may fade in the longer term as the market adjusts, but for now the risk is rising wage pressures in the months/quarters ahead. Alternatively, building more robust supply chains and manufacturing closer to home may create a more permanent level of inflation than we have become used to over the past several decades.

If this does occur, central banks are likely going to speed up their removal of supportive measures. While they can ignore transitory inflation pressures, wages are another matter. Investors in individual equities may want to dig a little deeper to ascertain their portfolios’ sensitivity to higher wages and reduce in case these pressures continue to build. Portfolio duration becomes important too. Long bonds, where fixed coupons are paid over long periods of time, will fare poorly in inflationary environments, as will businesses where current valuations pull in revenues expected many years down the road (i.e., growth businesses), unlike value and high-cash flow businesses that realize the value of a dollar today.

Source: Charts are sourced to Bloomberg L.P., Purpose Investments Inc., and Richardson Wealth unless otherwise noted.

Twitter: @ConnectedWealth

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.