For most grown-ups, Halloween isn’t all that scary but stock market corrections are, and we are in one now.

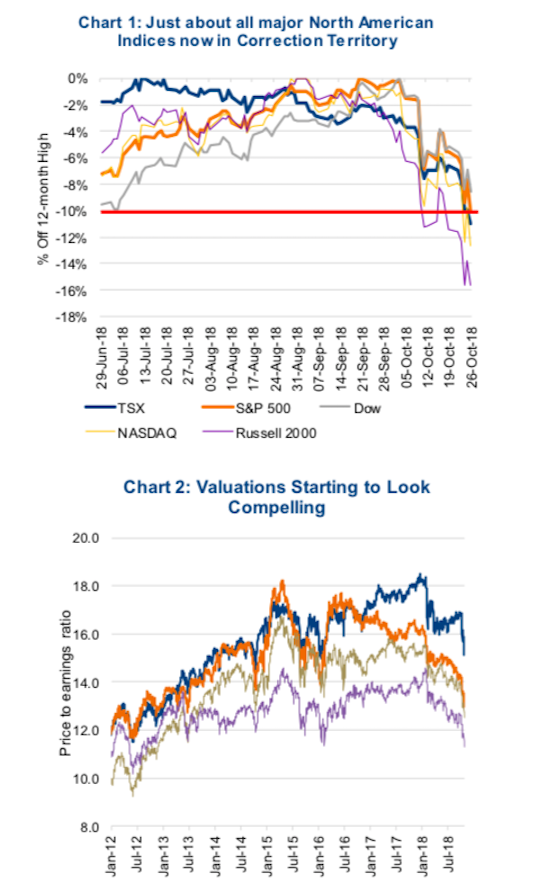

The TSX Composite, S&P 500, NASDAQ and the Russell 2000 small-cap index are all down more than 10% from their recent highs.

The Dow is holding on, but just by a few basis points (chart 1 below). The culprits are numerous at this point including an initial move higher in bond yields, continuing trade tensions and geopolitical issues centred around Saudi Arabia. Also responsible is growing evidence of softening global economic growth, weakness in emerging markets and some big earnings disappointments from a few technology heavyweights late last week.

This laundry list of market issues is largely the same as just about every period of strong market weakness, and that is what keeps most people from deploying capital at times like these. How many times have you taken a look back at past corrections and asked yourself: ‘Why didn’t I do some buying then?’ Most investors don’t because the negatives are front and centre getting a ton of media attention. All that attention triggers a behavioural bias called loss aversion, causing most people to simply sit on their hands.

Don’t worry, this ain’t an Ethos that is gonna tell you to ‘man up’ and buy the dip. Instead, we would like to remind you of the strong foundation under this market. Earnings are growing nicely (+23% so far in the U.S. earnings season), and the U.S. and Canadian economies are ticking along at a good pace, even well enough to weather steady rate hikes in both countries. The global economy is expanding pretty much everywhere, albeit maybe a tad slower than past quarters.

Valuations, which never signal a bottom but often identify good entry points, are now the most attractive since 2012/13 for Asia, Europe and the TSX. The S&P 500, at 15x, is attractive as well (chart 2 above). We would note how many times the S&P 500 price-to-earnings ratio dropped down to about 15x before bouncing higher. Secondly, if you want to be scared about something over Halloween, and for the future, it is corporate debt that keeps us more awake at night than the current bout of weakness.

Corporate debt

Allow us to paint a picture here. Coming out of the last global recession of 2008/09, the global economy experienced rather tepid growth for many years. A number of contributing factors led to this lower-than-normal growth rate. 1) Changing demographics certainly contributed, with many more savers than borrowers when compared to past recoveries. 2) The recession contained a global credit crash, which led to a deleveraging phase in the subsequent recovery. This sapped growth as balance sheets were somewhat repaired. 3) People and businesses simply became more conservative, as the wounds of the recession were still fresh.

In response, central banks kept overnight rates very low and embarked on quantitative easing. Deflationary pressures were evident and inflating asset prices via monetary policy helped the global economy get through this period.

Now think like a CEO during this period. Your company is profitable as the economy has recovered but there is little organic growth because the global economy isn’t growing very fast. Expanding the business organically, say by opening a new plant, seems risky as end demand isn’t rising. So how do you grow your business? You can make acquisitions, trying to do the old 1 + 1 = 3, thanks to cost cuts and synergies. Or you can return capital to shareholders via share buybacks or increased dividends. Everyone loves those.

Meanwhile, bond yields are very low, reducing the cost of debt. Add to this allure, passive bond exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have become very popular and have been receiving strong inflows of cash. This means if you issue a big enough bond which gets included in one of the major bond indices, a pile of passive investors will buy into your bond. And these passive investors never fight back on a bond issue that has lighter debt covenants (terms of the bond that protect investors).

Well, that is just what happened. 2018 appears to be lining up to be the 4th year with over $5 trillion in take-overs. The previous peak was $4.9 trillion in 2007. Meanwhile, corporate debt has ballooned to fund these deals or return capital to shareholders. Companies that have raised debt to fund dividend increases and share buybacks create a risky dilemma. In the short-term, it’s positive for share prices and existing shareholders (Yay, a dividend increase). But years down the road, when these bonds mature and need to be refinanced, future stakeholders will have to bear this debt burden that was used to return capital to shareholders in previous years. And if the business has not grown and/or interest rates have risen, then the debt burden is even larger than before.

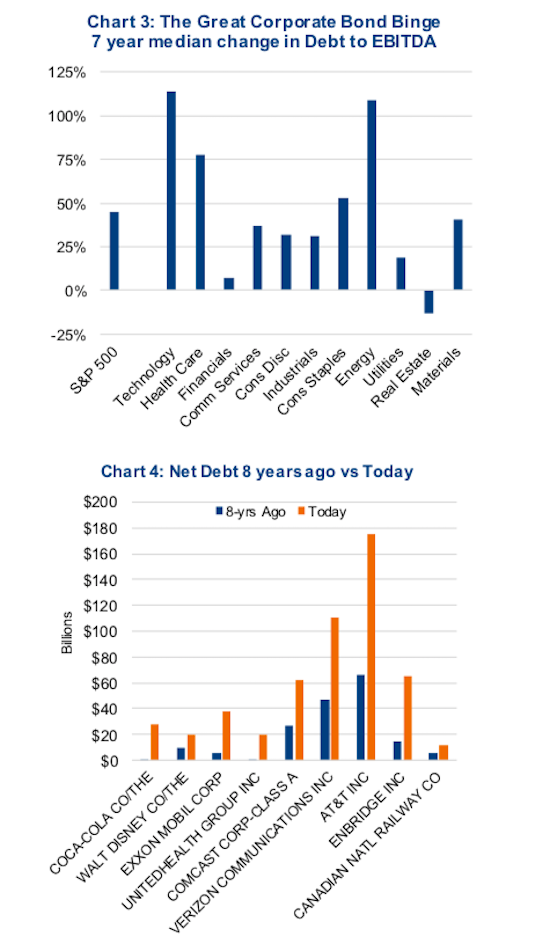

The bulk of the evidence indicates that corporate America, and corporations globally,

have gone on a debt-issuing binge. Chart 3 below is the 7-year median change in debt to

EBITDA (a measure of financial leverage), broken down by sector. Almost every sector

has expanded their debt leverage, some materially. Again, why wouldn’t they in a low 80% rate, easy issuance environment? We cherry-picked a number of big bellwether companies to show just how much some companies have increased the debt they are carrying on their balance sheet (chart 4 below).

Here lies the problem. If the increased debt does not commensurate with increased earnings power, this may create financial stress in future years. Perhaps the synergies from acquisitions don’t work out as well as expected, or the economy slows, or yields rise, creating a more expensive refinancing environment.

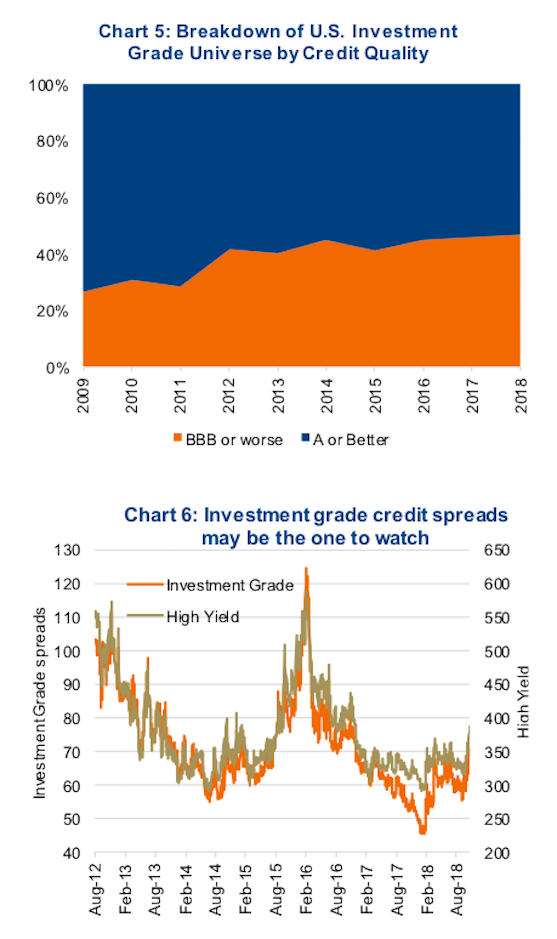

It is not hard to see where the stresses may appear. While many folks watch the high yield space for potential credit stress, the investment-grade (IG) universe has greatly decreased in quality over the years. In 2009, 72% of the U.S. investment-grade universe was rated single A or better. Today this is down to 53% (chart 5 below). In other words, almost half the index is sitting at the bottom credit rating that qualifies as investment grade. If these companies are downgraded one more notch they will move from investment grade to high yield (HY). That matters because there is roughly twice as much money invested in IG compared to HY, meaning there would be a painful reallocation of investors for bonds relegated down to HY.

This is not a big risk today with the economy doing fine. But next bear market may well see a divergence in companies that have been more responsible with their balance sheet compared to those that became hooked on easy money. It certainly has become a more prominent component of our fundamental company analysis. And we are paying closer attention to credit spreads at this point of the cycle (chart 6 above).

Charts are sourced to Bloombert unless otherwise noted.

Twitter: @sobata416 @ConnectedWealth

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.