The Federal Reserve (Fed) has increased the Fed Funds rate by 125 basis points or 1.25% since 2015, which had little effect on bonds until recently. Of late, however, yields on longer-maturity bonds have begun to rise, contributing to anxiety in the equity markets.

The current narrative from Wall Street and the media is that higher wages, better economic growth and a weaker dollar are stoking inflation. These forces are producing higher interest rates, which negatively affects corporate earnings and economic growth and thus causes concern for equity investors. We think there is a thick irony that, in our overleveraged economy, economic growth is harming economic growth.

Despite the obvious irony of the conclusion, the popular narrative has some merits. Fortunately, the financial markets provide a simple way to isolate how much of the recent increase in longer-term bond yields is due to growth-induced inflation expectations. Once inflation is accounted for, we shine a light on other factors that are playing a role in making bond and equity investors nervous.

Given the importance of interest rates on economic growth and stock prices, understanding the supply and demand for interest rates, as laid out in this article, will provide benefits for those willing to explore beyond the headlines.

Nominal vs. Real

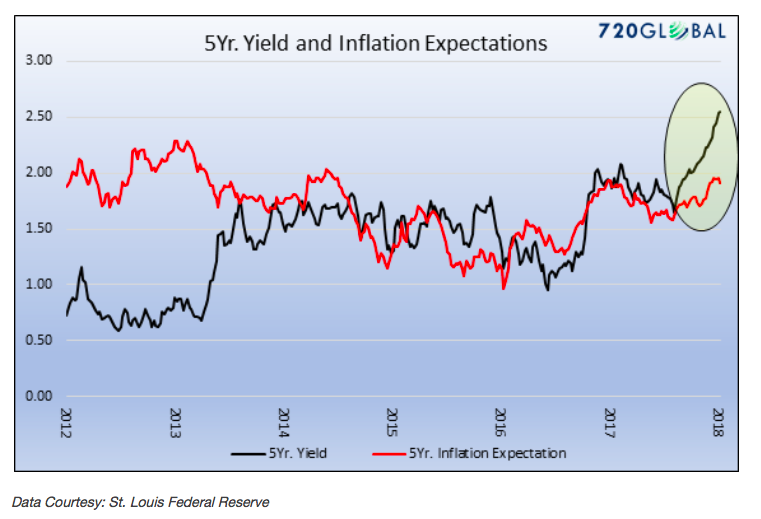

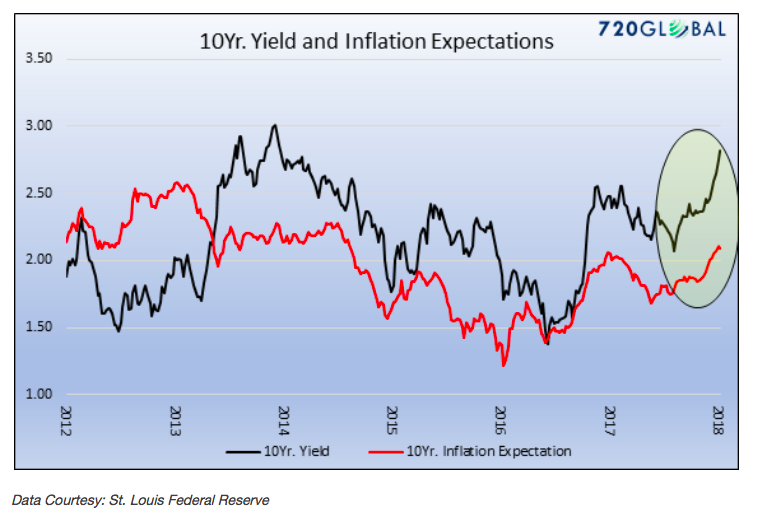

Since September of 2017, the yield on the five-year U.S. Treasury note has risen 90 basis points while the ten-year U.S. Treasury note has increased 75 basis points. At the same time, inflation, as measured by annual changes in CPI, declined slightly from 2.20% to 2.10%. Recent inflation data, while important in understanding potential trends, is by definition historical. As such, forecasts and expectations for inflation over the remaining life of any bond are much more relevant.

Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) are a unique type of bond that compensates investors for changes in inflation. In addition to paying a stated coupon, TIPS also pay holders an incremental coupon equal to the rate of inflation for a given period. In technical parlance, TIPS provide a guaranteed real (after inflation) return. Non-TIPS, on the other hand, provide a nominal (before inflation) return. The real returns on bonds without the inflation protection component are subject to erosion by future rates of inflation. To gauge the market’s expectations for inflation, we can simply subtract the yield of TIPS from that of a comparable maturity nominal bond.

During the same six month period mentioned above, yields on five and ten-year TIPS increased 30 basis points. As shown below, this means that 60 basis points of the 90 basis point increase in the five-year note and 45 basis points of the 75 basis point increase in the ten-year note are a result of non-inflationary factors. The graphs below highlights the recent period in which five and ten-year yields rose at a faster pace than inflation expectations.

By isolating the widening gap between nominal and real yields on Treasury notes of similar maturities, we establish that there are other factors besides inflation that account for about two-thirds of the recent march higher in yields. Below, we summarize the potential culprits affecting both the supply and demand for U.S. Treasury debt offerings, which should help uncover the factors other than inflation that are driving yields higher.

Supply Factors

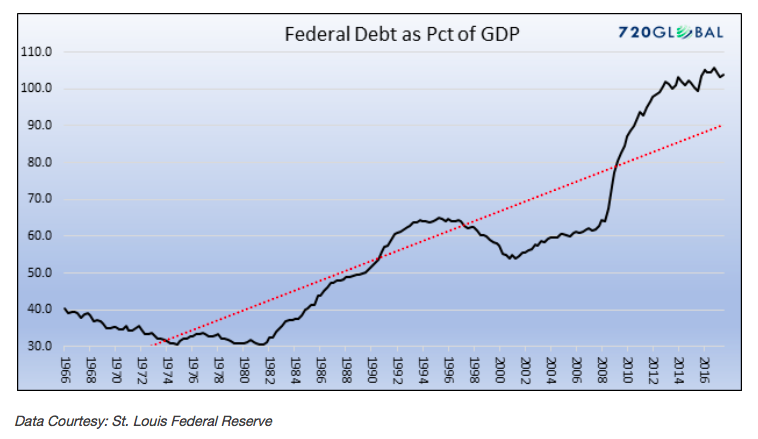

The most obvious influence driving yields higher, in our opinion, is the prospect of larger Federal deficits in the coming years. The tax reform package boosts the deficit over the next ten years by an estimated $1.5 trillion, and the recent two-year continuing resolution (CR) for government spending adds an additional $300 billion of debt to the U.S. Treasury’s ledger. We remind you these are in addition to Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts for sharply increasing deficits due to social security and other previously promised entitlements.

As if deficit spending approaching that of the financial crisis of 2008 is not shameful enough, the administration’s latest budget proposal is even more daunting. Based on the proposed budget, if we optimistically assume that the current economic expansion can last for ten more years without a recession and that GDP can grow by about 1.50% more than that of the last decade, then the deficit will grow by “only” approximately $8 trillion by 2027. Keep in mind; debt outstanding tends to grow by a larger amount than stated deficits due to accounting gimmicks used by the Treasury. Before including Trump’s budget proposal, the trajectory of Federal debt outstanding is forecast by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to increase by $1.1 trillion on average in each of the next five years.

To put that into context with the nation’s ability to pay off the debt, the economy has grown by approximately $500 billion a year on average over the last three years. Federal tax receipts as a percentage of GDP over the last three years have declined from 11.5% to 11.1%. If the economy grows $500 billion, we should expect an additional $55 billion of tax revenue. These numbers emphasize the extent to which elected officials from both parties have radicalized the budget process and the acute state of fiscal irresponsibility now in play.

Don’t dismiss the magnitude of $20 Trillion in U.S. debt and it projected growth rate. It is larger than the debts of the next four largest debtor nations combined.

Demand Factors

“Deficits don’t matter.” This frequently quoted statement leads many to believe that our nation’s debts will always be funded by willing and able creditors. To their point, rapidly increasing federal debt levels of the last thirty years have been easily funded and at increasingly lower interest rates.

To better gauge whether we can expect said support to fund the increase in projected debt issuance, we analyze the two largest holders of publically traded Treasury securities, foreign investors and the Federal Reserve.

Foreign investors hold 43% of all publically held Treasury securities outstanding, commonly referred to as “marketable debt held by the public.” China and Japan top the list, with each holding over $1 trillion of Treasury debt. The graph below compares foreign holdings of U.S. Treasury debt and the entire stock of public U.S. Treasury debt.

Will foreign buyers continue to grow their holdings by over $400 billion each year?

To help answer that question, consider:

- Over the last year, foreign holders have purchased approximately 5% of new debt compared to a range of 40-60% since the recession of 2008.

- Since 2015, foreign holders have increased their Treasury security holdings by $151 billion while $1.591 trillion of new Treasury debt has been issued.

- Since 2015, Japan has reduced holdings of US. Treasuries by 12% or $141 billion.

- Since 2015 China has reduced holdings of US. Treasuries by 4% or $52 billion.

The second largest holder of U.S. Treasuries is the Federal Reserve. Quantitative Easing (QE) was a major part of the Feds economic stimulus and bailout program of the 2008/09 financial crisis and continues to this day. QE is essentially the act of printing money to purchase debt securities from the market. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Fed holdings of U.S. Treasury securities rose from $474 billion in March 2009 to a peak of $2.40 trillion in December 2014, an increase of 416%. That balance was held stable through the end of 2017. To put that into context, as of September 2017, mutual funds, pension funds, and insurance companies held a combined $2.47 trillion of Treasury debt.

As we discussed in the Fed Giveth (LINK), the Fed has recently begun reducing the size of their balance sheet, and therefore its holdings of Treasury securities are slowly shrinking. They began in late 2017 by reducing the amount of Treasuries held by $6 billion per month and will increase the pace by $6 billion every three months until they reach $30 billion per month. This schedule, if reliable, implies that the Fed will reduce their Treasury holdings by $225 billion in 2018 and $351 billion in 2019. In this way, the reduction in Federal Reserve holdings is an incremental supply of Treasury securities to the market. And when the supply of bonds increases, yields should rise.

The absence of the Fed as large Treasury holders and the reductions in holdings and new purchases of Treasuries by China and Japan should have similar effects on yields, although the magnitudes may be different. So, rising yields are not just about inflation, whether realized or expected, it is also about the changes taking place in supply and demand simultaneously.

Summary

Vice President Dick Cheney was quoted in 2002 as saying “deficits don’t matter.” With the staggering accumulated deficits of the past few years, we are about to test Cheney’s theory. The powerful economic environment of the 1980’s and 1990’s allowed for the accumulation of federal, corporate and personal debt. In this millennium, the growth of debt accelerated, but the tailwinds supporting economic growth have weakened substantially.

Just because we were easily able to fund deficits of years past does not mean we should be so naïve as to think it will be easy going forward. As described above, the circumstances we face today are far more challenging than those of past years. The confluence of these events argues that investors should prepare for a new paradigm and not get caught flatfooted trusting in outdated narratives.

We leave you with a bit of wisdom from investment guru Bob Farrell, Former Chief Stock Market Analyst Merrill Lynch

“In the early stages of a new secular paradigm, therefore, most are conditioned to hear only the short-term noise they have been conditioned to respond to by the prior existing condition. Moreover, in a shift of long-term significance, the markets will be adapting to a new set of rules while most market participants will be still playing by the old rules.”

Twitter: @michaellebowitz

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.