This is part 2 of our investing research series on changing consumer and retail trends. (Read part 1 here).

This post was written with Chris Kerlow.

The way we spend our time and money has been changing. Selfies are a new form of ‘art’ work, more communication is done with emojis and worser grammar than ever before and shopping continues to move out of the mall to your phone.

The only certainty is that change will continue for the consumer and retail.

Your favorite activities, brands and social networks are unlikely to be the same in ten years as they are today. Some of these changes have accelerated in recent years with the proliferation of broadband technology, connectivity and digitization. Companies that were early adapters to change have stolen share from slower or less successful adapters.

However, we do not think the current winners such as Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN), Facebook (NASDAQ:FB), Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL), Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX), Alibaba (NYSE:BABA) will be the only companies standing when the dust settles. New players will emerge and many laggards will battle back.

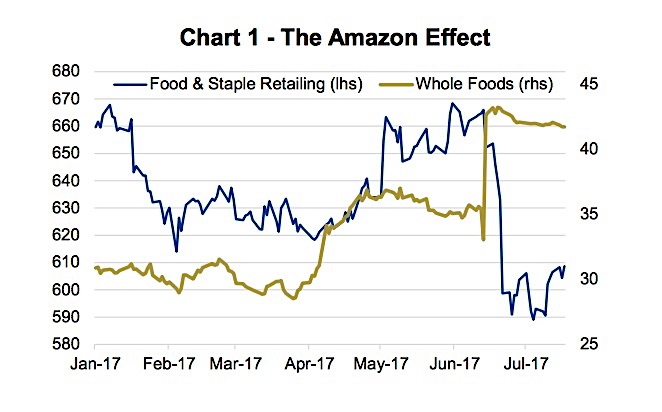

Most shifts in the market do not happen overnight and take time to develop. When it becomes glaringly obvious a shift is taking place, markets have a bias to overreact to new information surrounding that change. As an example, consider the recent announcement that Amazon was acquiring Whole Foods. This one transaction was seen as monumental for grocers and food delivery companies (chart 1 below). It was as if it marked the start of a slow death for your local supermarket. One can draw parallels to the impact that ecommerce has had on mall foot traffic and on retailers.

The reality is that food delivery isn’t new. In fact it has been around for centuries initially with local farmers delivering product directly to consumers (who remembers the milkman?). Then, the advent of the supermarket enabled a bulk purchaser to offer much lower prices and more variety to people who picked up their food from the store. That premise remains today. If consumers have groceries delivered to their home then the total embedded cost will be more than it would if consumers picked it up themselves. That cost may be subsidized by a company like Amazon. However, delivery of large, bulky consumer staple items at low cost can present challenges to the business of grocery delivery, particularly outside densely populated metropolises.

The majority of consumers are price sensitive, particularly for staple items which price can easily be compared across various sources. Consider milk delivery, the earliest survey was done by the Department of Agriculture in 1963, when nearly 30% of Americans had milk delivered. By 1975, that fell to 7% and in 2005 it was just 0.4%.

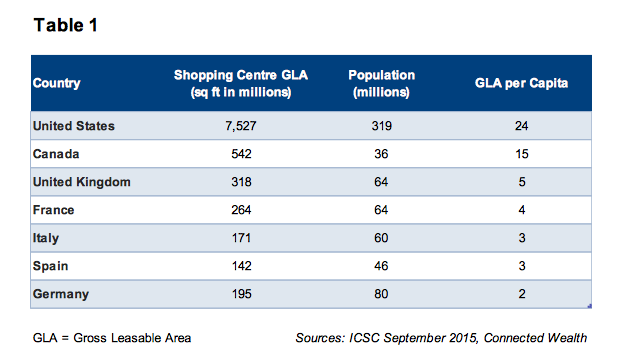

It is debatable what exactly transpires in grocery delivery. Critics will be quick to point out the similarities to what happened to large department stores once Amazon started gaining traction. Just ask executives at Sears, which was forced into bankruptcy last week, or at their beleaguered competitor JC Penny. The success of large malls anchored by large department store or a core tenant led to an egregious expansions of retail square footage throughout America. Gross Leasable Area for retail per capita is by far the highest in the U.S. (table 1 below).

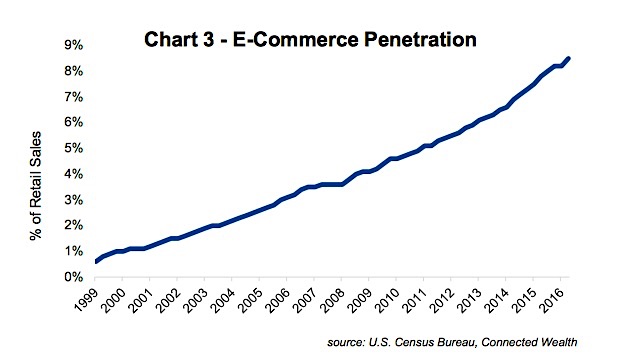

We believe the trend in declining mall traffic will continue and that the adoption of online / mobile sales will continue to gain penetration (chart 3 below).

From an investment perspective, it does appear these themes are widely known and reflected in the market place. Given our focus on dividend paying companies, we have gained exposure to this theme in derivative plays. This includes International Paper, which makes some of the packages used to ship ecommerce merchandise. Their largest customer is Amazon. Or names like UPS and TransForce, which deliver the goods from the sender to your door.

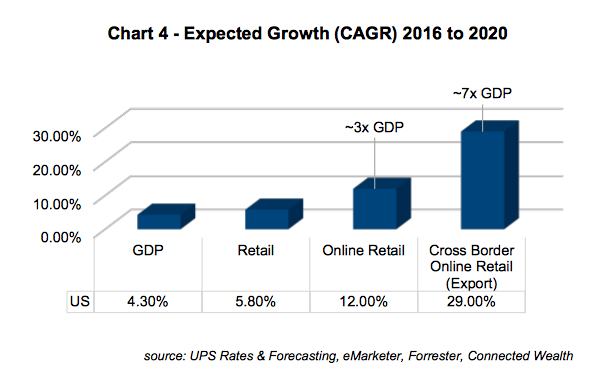

The visibility of continued success for online shopping (chart 4 below) has allowed logistics companies like UPS and TransForce to invest and build highly integrated networks. This has made it cheaper and more efficient for retailers to go directly to consumer across the globe. This is putting heavy pressure on intermediaries, which we generally try to avoid. Consider a company such as Foot Locker. Its business model involves buying high-end athletic shoes and apparel from a variety of suppliers so that customers can compare, try them on and purchase them in store. If you like your shoes then you now know your size. For your next purchase you can just go on to a company’s website and order them directly. Online vendors often have a larger selection and more options. Also, they frequently offer free shipping and returns, which supports the packaging and shipping industry.

Tastes are changing too. As the population ages, spending is rising more on experiences compared to big ticket items. This is supporting a secular tailwind for what are deemed experiential companies. One company we have owned in many portfolios for some time is Carnival Corp. that benefits from experienced driven spending.

Within the consumer sector there are certainly some industries that are more at risk of on-line competition and some that are less at risk. Home Depot, which targets the “do it yourselfer” and whose products are often large and bulky, has long been viewed at low risk from online. This view is being tested with Amazon getting into the appliance business last week. Even Loblaw or North West Co., two of our country’s biggest grocers, offer consumers the opportunity to walk around the store trying samples, the fresh scent of baked goods and seeing the produce that will be on their table.

The world will continue to evolve, companies that resist change will likely be disrupted. We are in an era of investing where successful disruptors like Amazon, Netflix and Facebook are given a pass by investors to operate at a loss or even to provide services below cost so long as they continue to gain users and subscribers or to grow their social network. This notion was captured eloquently last week during the Netflix earnings call, when CEO Reed Hastings said, “the negative free cash flow will be an indicator of enormous success.” While that may be true in the short run, companies cannot lose money forever. When the market takes away the free pass we could see a shift in how these stocks are treated.

Thanks for reading.

Charts are sourced to Bloomberg unless otherwise noted.

Twitter: @sobata416 @ConnectedWealth

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.