Michael Harris of Price Action Lab penned a very thought-provoking post yesterday that slices through the noise on the Russell 2000’s recent Death Cross. In spite – and because – of it’s balance and evidentiary modesty Mike’s piece will not get the wide reading it deserves as financial news media ominously wails about the pattern to demagogue the morbid fascination and easily-stimulated anxieties of casual market observers who will wonder if this nihilistic technical meme doesn’t confirm that the equity bubble they feared was there all along is finally bursting. All of which is exactly why you should read it.

Here I’ll focus on a key passage offered by Mike:

Rejecting a pattern like the death cross in Russell 2000 on the grounds that it is not a very strong signal based on the past is wishful thinking and a formal logical fallacy since no indicator is sufficient for price action. The significance of technical indicators is determined based on statistical analysis and sufficient samples.

As an active trader who runs rule-based programs that admit an element of discretion, Mike and I part ways on his second assertion; but it’s not so much a disagreement as a different conversation. However, his first statement is theoretical bedrock for any technical practitioner who wants to convert their analytical acumen into profitable action.

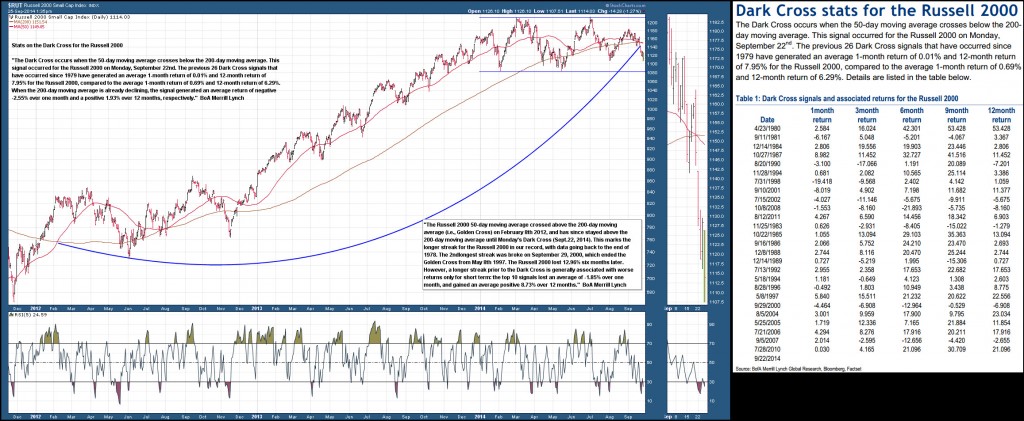

I’m not really interested how the Russell 2000 Death Cross performs here. Michael’s analysis is complemented well my friend (and much-beleaguered Bengals fan) Ryan Detrick‘s observations this past week; along with this chart from See It Market’s Sheldon McIntyre featuring stats from BofAML’s recent “Dark Cross” note (click image to zoom):

This data completely nullifies the fear-mongering and petty sensationalism of broader media’s attempt to leverage the edgy arcana these names give to what is really a prosaic technical event. The stats above may or may not surprise you; but they are more likely to make you shrug than cringe, or cheer. The fact of the matter is: Death Crosses – like Hindenburg Omens and all the other classic monsters in the Chartist’s Bestiary – are neither inherently bullish or bearish. Historic pattern data can be rendered, divided, sliced and otherwise legitimately appropriated in a number of ways to back up a sound thesis on the market analyzed.

Mike goes on to state, “the significance of technical indicators is determined based on statistical analysis and sufficient samples.” As a builder of rule-based technical systems, Mike does a fantastic job bringing empirical rigor to a discipline that is often described as “more art than science”. Too often “art” is a pretense for sloppiness and subjective license (which also helps makes a market) rather than inspiration or what I’d call principled discretion. Statistical analysis and representative sampling are essential tools and act as failsafes to counter and contain the “human, all too human” foibles each of us brings to investing/trading.

At the same time though (and this isn’t to contradict or criticize Harris’s work), there is no science of technical analysis of financial markets; and there isn’t likely to be anything approaching one, ever. The pursuit is a meritorious one; but it’s a modernist anachronism that naively assumes whatever can be quantified can also be circumscribed. As the chaos theorist Ian Malcolm wryly noted in Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park, a book about the catastrophic hubris of human attempts to constrain dynamic systems: “Science has always said that it may not know everything now but it will know, eventually. But now we see that isn’t true. It is an idle boast. As foolish, and as misguided, as the child who jumps off a building because he believes he can fly.”

It’s tempting to suppose otherwise – that is the reductionistic mantra of contemporary scientific endeavor, after all – and the careers and projects of many academicians in quantitative finance and economics are reliant on doing so.

But any academic evaluation patterns – such as the Death Cross – is only accomplished by treating the market as a static, closed system. Rules are decided, criteria are delineated, necessarily limited samples are generated with the usual attendant errors, and human discretion – except for the meta-discretion exercised by those who contrive and review the study – is structurally excluded from consideration.

These steps are taken to make the subject of study – something as modest as a single chart pattern – “tractable” and the model devised to study it appear adroit. But the phenomenon that results is an other world, reduced in complexity only to the degree necessary to grant the author omniscience over it.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb discusses this transmogrification of wild and chaotic systems markets into docile statistical simulacra in The Black Swan, categorizing practice as the ludic fallacy (Lat. ludus, or “game”): “the misuse of games to model real-life situations.” Any quasi-scientific appraisal of chart patterns must make recourse to the “textbook examples” found in the likes of Edwards & Magee, Murphy, Schabacker, Prechter, Nison, DeMark among others to even have a coherent concept of study. Attempts to quantify the performance of what have become Platonic, classic pattern archetypes in the collective market mind – as typified by their codification in the MTA’s Body of Knowledge – necessarily require objective criteria.

The paradox of pattern, indicator or even system efficacy is that whatever there is of it is imputed by the past; but can only ever be proven in the future.

The real black swan that frustrates all attempts to create a science of indicators and patterns is human discretion. The intractability that human agency introduces sorts along two lines.

- Propagation of Uncertainty: The first is covered by a diverse body of critiques put forth by behavioral economists that amount to a terminal indictment – or least demand a radical reworking – of rational choice theory. The import for markets is that the admission of human irrationality into market models floods and subverts them with a propagation of uncertainty so overwhelming the model is rendered hopelessly obsolete. If markets are the sky, evaluating the role of human agency is tantamount to staring into the sun. The reductionist program is hilariously ill-equipped to devise a science of patterns, indicators or asset classes: not because it is impossible, but because our analytical acuity is so inadequate to the task of pursuing the scientific method when confronted with the combinatorial explosion of variables that is a free and liquid market.

- Theory and Execution: the second is more interesting, and more hopeful. Traders are fallible, but they’re also creative. The Russell 2000’s Death Cross offers a perfect example. This pattern’s platonic form – that of a key shorter-term moving average crossing beneath a longer-term moving average – is prima facie bearish. But as the data mentioned above points out, the truth may be quite different. Whether the pattern is efficacious – and what outcome it is efficacious for – has almost nothing to do with the data and everything to do with the practitioner’s application of it. It is the trader who who decides.

Some traders will look at the Death Cross data and find to remain neutral in what is a very choppy year for the Russell 2000 Others will look, see a bullish statistical edge and devise a long trade setup or campaign. Some will enter a short on the Russell 2000 but not abide by the arbitrary and simplistic “stop and/or reverse long on a daily close where 50-Day SMA > 200-Day SMA” trade management criterion. Discretion in analysis and execution admits of other rules, variants and elaborations that will render the Death Cross profitable or unprofitable. The Death Cross – like all patterns – is bullish or bearish – it’s just a technical foil against which the practitioner measures risk.

There is no objective efficacy to patterns, indicators or systems. There is no verifiable “significance” that can be mutually observed before the pattern plays out, or the indicator/system signal is traded. Technical analysis is a tool – not a tutor, an oracle or an inerrant, evidence-based guide. Patterns have no innate “performance”: that is stuff of white papers treating technical events in the stasis of tractable scenarios, not those deploying real capital into a system fraught with unpredictability. “Efficacy” is something created by the trader alone.

Twitter: @andrewunknown

Author holds net short exposure in Russell 2000 at the time of publication. Commentary provided is for educational purposes only and in no way constitutes trading or investment advice.