It is the doom of men that they forget.

— Merlin

Beginning late last Summer, catastrophic market sell off analogs regained their seasonal popularity. Then, out of all proportion to the ink spilled arguing their persuasive merits, the analogs linked to the anniversaries of Black Monday (10/19/1987), Q4 1999’s asymptotic rise and – most contentiously – the Three Peaks & and a Domed House 1929 parallel (which observers such as Ryan Detrick dispatched) quietly filed in and out of view in anticlimactic succession.

The market in our time has a common fascination with Crash Disaster Tourism. Maybe it’s because of the concentration of major market sell offs in our generation? Or perhaps it’s the structurally impaired consumer confidence that has hardly bounced since 2009? Perhaps it’s a function of an increasing wealth gap that creates headlines insistent on a renewed prosperity while masking a recession-like socioeconomic malaise outside the 1%? At the bottom of it all, could it come from a primordial distrust in the Fed, whose policies – “supportive of asset prices” – have only proven efficacious for TBTF bank balance sheets and the stimulation of salutary second-round “wealth effects” for an already-monied elite?

Whatever the case (it’s all this; and more), the auguring of apocalypse by hard asset high priests and others is as popular as ever. If you’re waiting for that storied, all-pervasive eros for markets to so grip the proverbial “haberdasher with a hot stock tip” to sell, it could be a very long time in coming.

But insofar as our collective imagination is held rapt in the sway of weighing today against the most tragic vignettes in market history and remains enamored of narrative tropes of greed, absurd excess and regulatory incompetence/indifference (i.e. just about anything Michael Lewis has written about), we’re nurturing an array of cognitive biases that obscure the vast spaces of that history lying in between. Spaces that become faint in our memory because they’re away from the tail ends of the curve, but from which our vital senses of market equilibrium, nuance and probabilistic edges are derived.

It is this kind of crash-induced myopia that creates some major blindspots. As I wrote in January:

Bearishly seeking out signs of or taking bullish encouragement from the absence of conditions adhering to the standard bubble archetype inhabiting the market mythos could prove a tragic distraction when the next major correction or bear market shows up with other characteristics.

What results from our fascination with the lore of disastrous markets? A negative survivorship bias that brings the environments where risk and speculation died to life in our memory, leaving the comparatively prosaic spans in between to whither and fade from easy recall.

Why does this matter? Because any semblance of objective analytical rigor goes out the window when our mind pares the market down to a sample space of cataclysms that can be counted on one hand. And similarly, because the negativity bias that casts the shadow of these events over everything else can skew our appraisal of the present both positively (“it isn’t as bad as ‘bubble/ensuing bear market x’, so it isn’t bad”) or negatively (“it isn’t as bad as bubble/ensuing bear market x’, so it can still get much worse”).

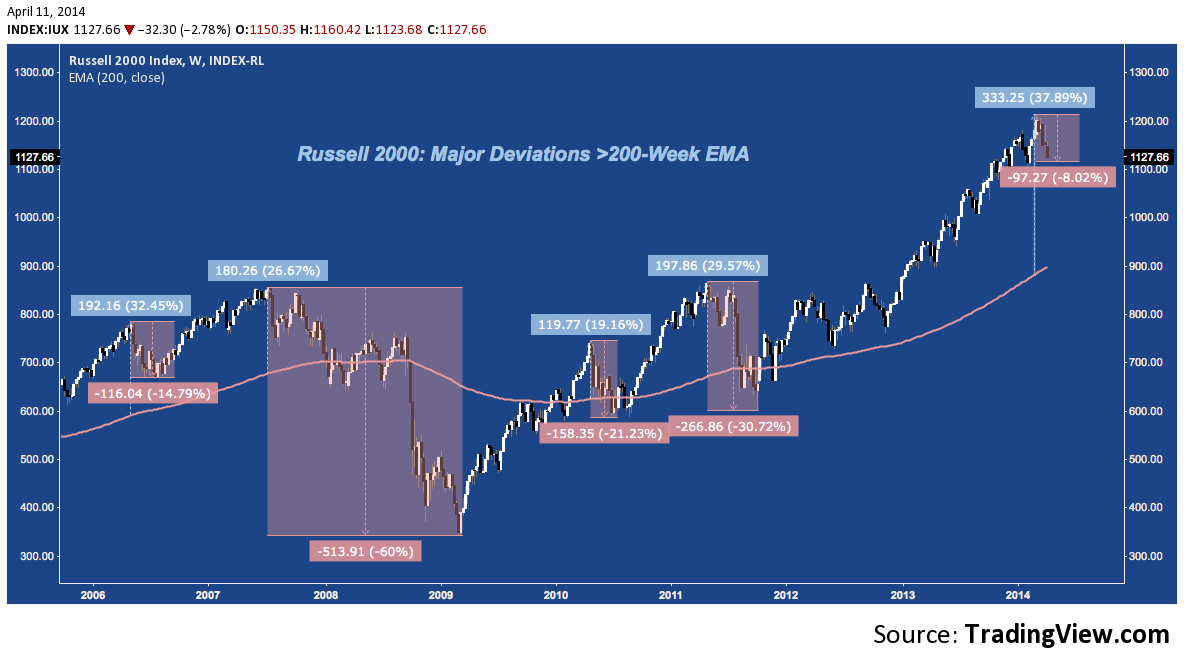

Let’s apply this to the current market environment. Small Caps/Russell 2000 (RUT, IWM, TF) has been in a masochistic race to the bottom with Tech/NASDAQ 100 (NDX, QQQ, NQ) during this pullback, each attempting to out self-immolate the other in pursuit of the dessicated victory laurel that goes to the worst performing index of the year. The Russell 2000 (through 04/14’s close) is -8.84% off March 4 all-time high, at an extreme 200-Week EMA Deviation of +37.89%.

If it sounds like Small Caps were hugely overextended last month, that’s because by the standard of recent market history – including 2007 and 2011 – they were:

Even though Small Caps had a blowout year in 2013, it’s still shocking that R2k was 50% further away from the 200-Week EMA last month than at it’s cyclical peak in 2007 at 26.67%. Though it is clearly more powerful, the current statistic isn’t half so vivid because 2008 hasn’t occurred adjacent to it. These are each major deviations from the prevailing long-term trend; but outside of the 2007-2009 period, do they even register? Excluding that period (and 2014) entirely, is it surprising to learn these corrections averaged -22.25%?

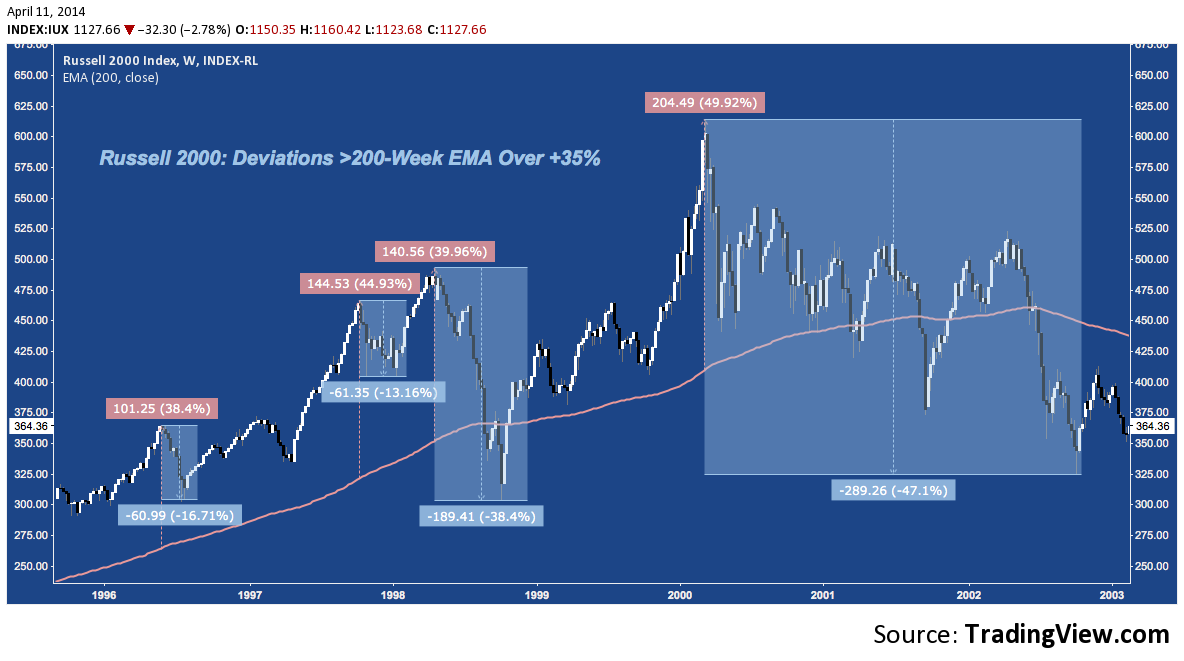

Compare this to 1995-2000. During that period there were 4 major tops featuring deviations from the 200-Week EMA above March 2014’s figure of +37.89%. As you might expect, Early 2000’s reading was very high (a record) at just under +50% (a figure reduced to less than +15% within 6 weeks). But forget 1999-2000 for a moment. 1996, 1997 and 1998 experienced one peak above +35% each. “Of course they did,” you might think; after all, the Russell 2000 more than doubled between 1995 and 2000. What doesn’t spring to mind so quickly are the deep corrections that followed each peak, averaging -22.76%.

It’s tempting to consider 1999 and 2007 alone because that is what the grand schema of the market’s collective negative survivorship bias compels us to do. A heuristic routine adapted to focus energy and attention on wariness of the biggest threats to our survival, our own negativity bias is only t0o eager to play along. But it’s the singular focus on these monolithic bubble archetypes that causes us to sublimate (or simply exclude) these other moments from memory.

If we concentrate solely on the “crashes” (which had markedly different deviation values, but average to 30bps higher than March 2014 at +38.29%), the total average decline is -53.55%.

In contrast, if we strip out the the “crashes” for an average deviation of +34.07%, we get:

- Mean Correction: -22.58%

- Median Correction: -18.97%

The periods we easily recall because of their traumatic imprint, predictably, suggest an implied additional drop for the Russell of -44.71%. The temptation – rightly, or not – to discard a move like this, relegating it to the realm of the highly improbable is very strong.

But does that mean a deep correction can’t unfold from here? No: we can infer from the average of the “forgotten” corrections only (the second set of stats above) a further decline of -13.74%. That carries the Russell 2000 to 938. These occurrences aren’t plentiful in the last 20 years – there were 6, or one every 3.3 years, with the last almost 3 years ago – but excluding them due to crash myopia and then writing off any hint of a cataclysmic decline as “bubble talk” could lead to a blindsiding negative surprising that takes R2k some 200 points lower from here.

Wrapping everything together, we have 8 corrections at an average deviation of +35.13% over the last 20 years on the Russell 2000 deriving from extreme deviations above it’s 200-Week EMA – that’s one every 2.5 years (at 33 months since July 2011 we’re slightly overdue):

- Mean Correction: -30.32%

- Median Correction: -25.98%

At an average bear market of -30.32%, this metric suggests an implied additional decline of -21.48% is in the offing, running to 845 – the site of the July 2007 and April 2011 highs – almost to the point.

What else does the anecdotal “wisdom” of the market push out of memory? How do the major narrative themes moving through social finance and mainstream financial media shape our own memory of market history; and for that matter, our personal history in and cognitive biases concerning the market? If price has a memory, the answers to these questions have huge and sprawling implications for our own investing and trading.

Twitter: @andrewunknown and @seeitmarket

Author holds net short exposure to the Russell 2000 at the time of publication. Commentary provided is for educational purposes only and in no way constitutes trading or investment advice.

Grim Reaper image via https://hdw.eweb4.com/wallpapers/1488/

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.