A unicorn is a privately held startup company valued at over $1 billion. The term was coined in 2013 by venture capitalist Aileen Lee, choosing the mythical animal to represent the statistical rarity of such successful ventures.

Unicorn hunting is becoming less appealing now that many large Initial Public Offerings recently have struck out rather than generate a guaranteed home run.

This was evident in 2019 stock market IPOs by names like Peloton NASDAQ: PTON, Lyft NASDAQ: LYFT and Uber NYSE: UBER, among others.

It was a different story at the start of the year. Coming to market was making some early investors much wealthier overnight.

Beyond Meat, Zoom, Crowdstrike all flew after their initial offering, but in recent months have given back much of those initial gains. The early hype was so exaggerated that even those closest to the companies thought it had gone too far.

The shift in sentiment has cooled the desire for companies to rush to the market. Last week even Saudi Aramco delayed their public offering by at least a few weeks.

On October 17, Endeavor Group, the Hollywood agency, pulled theirs as well, citing unfavorable economic conditions and negative sentiment. These delays are doing nothing to alleviate investors’ concerns about the deal’s prospects.

WeWork’s valuation was slashed as it approached the public markets, causing them to abandon their plans and a multi-billion-dollar write- down for SoftBank. Other high-profile offerings on deck such as McAfee, Poshmark and Airbnb, also must be wondering if they should put the unicorn back in the stable until things turn around.

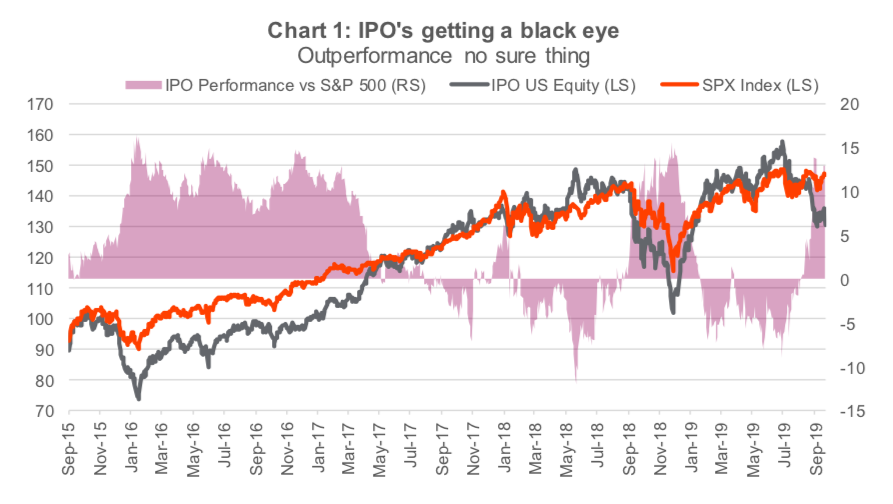

The market’s response has not been quite as ebullient as Silicon Valley would like to see for 2019 stock market IPOs. This is illustrated in Chart 1, which tracks the performance of the aptly named IPO ETF and the S&P 500.

Amid current conditions, private companies are looking at other ways to go public. A rarely used approach but something that both Spotify and Slack Technologies both used is a direct listing. The biggest advantages are that it requires no fundraising, costs much less and the marketing roadshow efforts are far less necessary. The downside is that there is no new capital raised during the process. This isn’t a problem for those private companies that are flush with cash and simply looking for a way to cash out shareholders with large concentrated positions in the company.

According to media reports, Airbnb – valued around $35 billion – is considering a direct offering instead of an IPO next year. And as a sign of the times, an event was held in San Francisco on October 8, described in marketing material as an “industry- led symposium on the benefits of the direct listing approach”.

When you already have a dominant market position and an established business, an influx of capital and diluted ownership is less appealing than having easy access to a market listing and instant liquidity. But a direct listing is not a sure thing to buck the IPO malaise – for instance, Slack shares are now down about 15% since its debut.

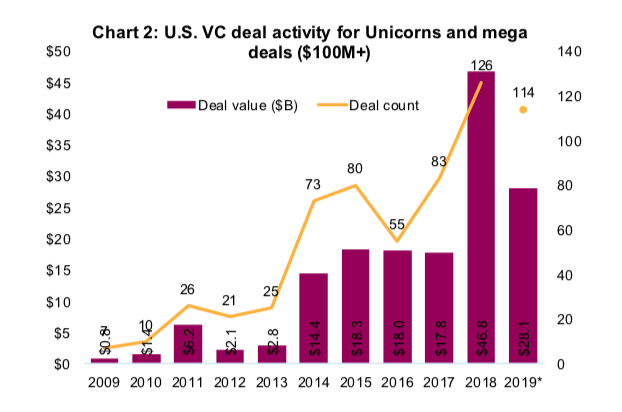

The venture capital market is still humming with deals, with more-than-ever funding directed toward Unicorns in 2018. Late-stage investments have been increasing in number, with investments in unicorns and mega deals ($100M+), nearly doubled compared with 2017. So far in 2019, we’re seeing lots of deals, but the value will likely come short from 2018 levels. (Chart 2)

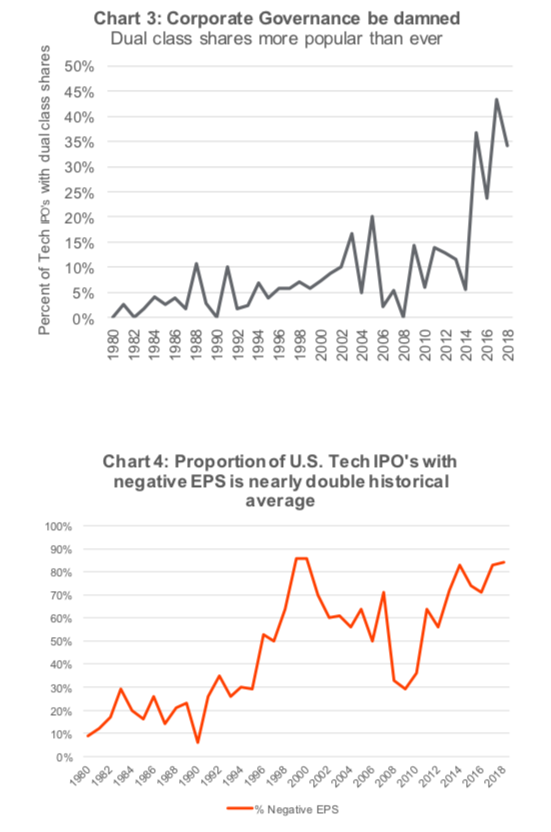

In line with index rules, stocks with multiple share classes are often not added to indexes designed by FTSE Russell and S&P Dow Jones. Among those impacted are 7 of the 10 largest IPOs so far in 2019. Not being in an index means that the shares are not supported by the billions of dollars flowing into passive products that follow those indexes.

However, one of the benefits is avoiding much of the worry about pesky public market corporate governance. Chart 3 shows the rising popularity of dual-class shares in technology IPOs going back to 1980. This trend is troubling, and investors should not be as willing to forego voting rights.

With the increase in volatility over the past few years, we have seen investors flocking to the private market to invest in corporations where the valuation only changes during a capital raise – typically an upward move from the last round. The National Securities Markets Improvement Act of 1996 made it much easier for startups to raise capital by reducing disclosure requirements.

This opened the doors for venture capital and private equity and likely contributed to the boom and bust of the tech industry in the early 2000s. Many market pundits are drawing parallels to that era as 2019 has marked the most capital raised by unprofitable companies since the year 2000. It’s not just the VC market that’s as willing as ever to open their chequebook to unprofitable companies. Chart 4 illustrates the percentage of Tech IPOs with negative earnings. Seems like market enthusiasm/delusion is on par with the tech boom when any company that placed a ‘dot com’ on their name garnered immediate attention, no matter the underlying business strength or sense.

Tech bubble 2.0?

It’s been said that this is the age of disruption. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s now famous motto is to “Move fast and break things”. While Facebook laid the trail for many unicorns to follow, and his motto led many entrepreneurs to venture off to disrupt established business models (think taxis and hotels), perhaps we’ve reached a point where we’re in the age of faux disruptors. Technology has been billed as the answer to all of our problems, and at times can create much euphoria about growth.

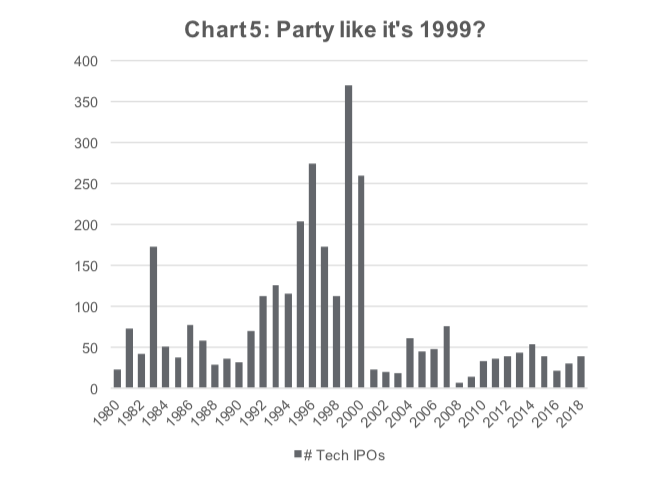

While a lot of fuss is being made of the IPO misses this year, the market is far from a bubble. Though the dollar amount is higher than average presently compared with 1999, IPO activity is nowhere near as fanatic (see Chart 5). Investors might be wary of new deals, but there is little mania in the market.

What is the main issue underlying the recent troubles? Pricing might be at the root of the problem. That is, deal pricing might be more art than science, no matter what bankers may say. It’s a delicate process to determine what the market is willing to pay. Important elements include: the assessment of management quality; business quality; level of interest (some say ‘greed’) in the market; valuation of comparable companies; and ultimately the founder’s ideal asking price.

Portfolio Implications:

The run up of new IPOs earlier this year and subsequent underperformance is another example of how fast sentiment and investor behavior can pivot. Humans are all prone to a variety of biases and heuristics; the key is to control your emotions and not get caught in the fear of missing out. Faux meat and ride sharing are innovative technological disruptors, but even a great company might not be a great stock.

It is important to stick to a disciplined investment approach focused on company fundamentals and future earning power, and determining if those future earnings are worth more or less than what is being priced in the market. Warren Buffet summed it up eloquently when he said, “Don’t get caught up with what other people are doing. Being a contrarian isn’t the key, but being a crowd follower isn’t either. You need to detach yourself emotionally.”

Source: All charts are sourced to Bloomberg L.P. and Richardson GMP unless otherwise stated.

Twitter: @ConnectedWealth

Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors, and do not in any way represent the views or opinions of any other person or entity.