Behind the most recent upgrade to the weight of the evidence are signs that global central banks are becoming more accommodative. Out of 34 central banks around the world, 11 have made interest rate changes in 2019. Of these, three have tightened and eight have eased.

Overall, more than half of all central banks are now easing monetary policy. All of the net gains in global stocks in the past 30 years have come when a majority of central banks have been lowering interest rates. Whether talking about the Fed specifically or central banks generally, the old adage appears to hold: don’t fight them.

The Federal Reserve is in the minority of central banks whose most recent action was to raise rates. The Fed has spent most of the first half of 2019 trying to pivot away from its December 2018 rate hike. While it declined to cut rates at its June meeting, the Fed is expected to move into the easing camp later this year, perhaps as soon as July.

While the last two rate-cutting cycles (2001 and 2007) can anchor investor expectations for a negative stock market reaction, a more complete history suggests the key question is whether an initial rate cut is followed by an economic recession. If the economy is experiencing a growth scare but not moving into recession, a rate cut could be a positive catalyst for stocks (and the economy).

The Fed at this point appears poised to cut rates this year and would likely need to be dissuaded from pursuing this path. There is a risk, however, that the Fed could cut rates and still disappoint the market. As recently as March, fed funds futures saw a 90% chance of no change in rates in 2019 (with a 10% chance of a 25 basis hike by the end of the year).

Those same futures now see a 60% chance of 75 basis points or more of easing, with no chance being seeing of rates finishing the year at the current level. There is an unfortunate conflation between financial market gyrations and business cycle dynamics (there can be overlaps, but they are not identical). While it may provoke disappointment, policymakers now more than ever need to look through the former and focus on the latter.

The Fed has acknowledged wanting to see evidence of economic trends and does not want to be reacting to single data points. The recent focus by the Fed appears to be on growth dynamics, but it is not clear to us that inflation risks are as benign as the headlines suggest. At the May FOMC meeting and in speeches shortly thereafter, the Dallas Fed’s Trimmed-Mean PCE inflation index was emphasized a providing a clearer picture of underlying inflation. As trade-related uncertainties have dominated the narrative, inflation has slipped from the headlines. With the Dallas Fed’s measure showing inflation at its highest level since 2012, the Fed may not have the room/desire to fully accommodate the market’s expectations.

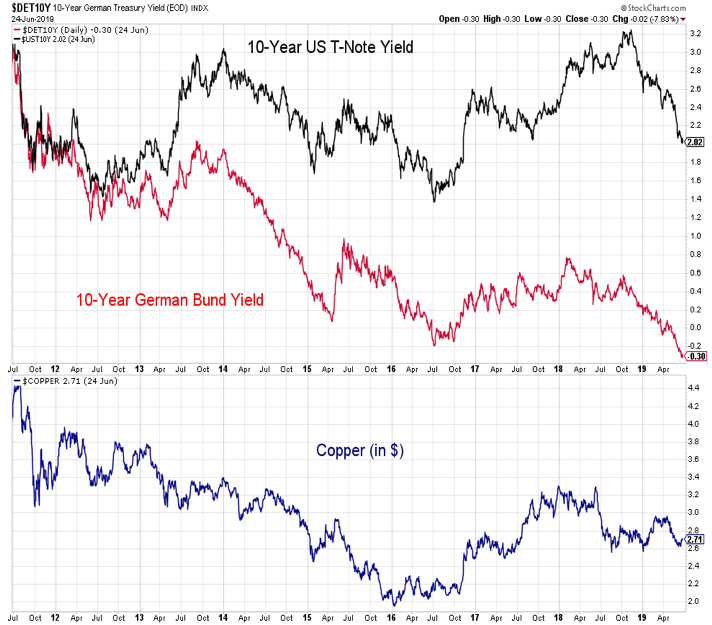

Economic data gets released with a lag and can be subject to revisions. Market-based indicators can be more timely, and while not subject to revision, can get carried away by emotions. Bond yields, both at home and overseas, have been moving lower since peaking in 2018 (US Treasury yields peaked in December, German Bund yields peaked in January of last year). The bond market appears to be arguing for increased accommodation by the Fed and other central banks.

Copper prices tend to move in line with bond yields, though in the current case have shown more resiliency and not moved to new multi-year lows. This suggests there may be a reason for more economic optimism than what is suggested by the bond market. A break to new lows in copper would increase our concern about the global economy.

The shift in Fed policy is a real-time reaction to rising levels of economic uncertainty as trade-related tensions begin to ripple through the economy. While the immediate focus may be on the resolute to talks between the US and China, it is unclear that those talks have a foreseeable end-game. Moreover, tariff threats seem to be increasing rather than decreasing and the 2020 presidential election race is likely to heat up over the second half of 2019.

While the Fed may try to offset this uncertainty by lowering rates, it is not altogether evident that lower rates would do much to temper those uncertainties and it may be the case that inconstancy of the Fed as been adding to those uncertainties and adversely affecting its own credibility.

Elevated uncertainty comes at a tough time for the global economy. Growth has been moderating for over a year and the green shoots that had been emerging have since shriveled. The global manufacturing index has moved below 50 (indicating a contraction in activity, not just moderating growth) and is at its lowest level since 2012.

One small positive is that even as growth has continued to slow, this weakness has not exceeded expectations. The economic surprise index for Europe suggests that relative expectations, the incoming data is a good as it has been since 2017, a big improvement over last year and much of the first half of 2019.

Export orders have been hit hard as actual and threatened tariffs weigh on global trade. After some preliminary stabilization in the first half of 2019, the percentage of countries seeing new export orders expanding has turned lower. There are a number of ways to quantify the effects of these tariffs and with evidence emerging that Vietnam is being used as a conduit to circumvent some of the tariffs imposed on China, estimates of dollar impacts could be distorted.

This summary resonates with us: In terms of applied tariff rates, the US economy is moving from being the 19thmost open economy in the world to being the 116th, just between Algeria and Senegal. If this is a path to growth, it is not one described in many economic textbooks.

So far, the U.S. economy has endured the weakness overseas and uptick in uncertainty. Growth is slowing, but business conditions (as measured in real-time by this Philadelphia Fed-published index) been resilient. In fact, based on this index, the economic conditions that have been present over the course of the expansion are largely intact. This does not preclude weakness from emerging, and that in fact is one of our two primary concerns as we move through the second half of 2019, but in the past, global weakness has been a storm to be weathered not a precursor to recession in the U.S.

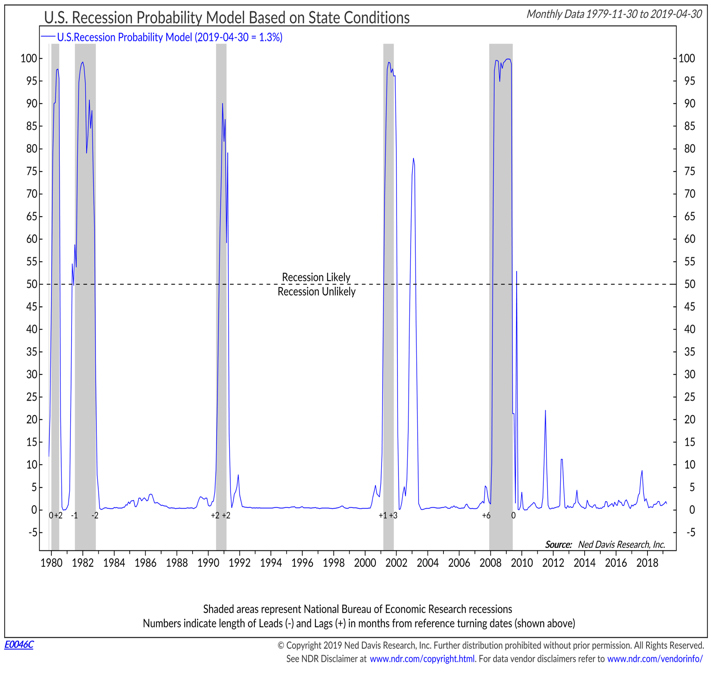

Despite the headlines, recession risk in the U.S. remains low. That is the message from this recession probability model based on actual state-level conditions. There are pockets of weakness (regional Fed surveys are moving sharply lower) and indicators to watch for evidence of further deterioration (initial jobless claims, evidence of layoffs at small and mid-sized firms) but the more likely outcome for the U.S. economy at this point is a growth scare and not the imminent ending of the now decade-old economic expansion.

One area of specific focus over the course of the second half of 2019 will be measures of economic confidence. A significant decline in confidence would increase downside risks for the economy.

continue reading on the next page…