Stock buybacks are a conflict of interest which has been exposed primarily through extravagant levels of executive pay and income inequality. As an extension of previous articles on this topic, 720 Global digs even deeper to expose the truth behind the logic and rationale of corporate stock buybacks.

In his 1995 speech at Harvard University, Charlie Munger (Vice Chairman Berkshire Hathaway) walks through a multitude of causes for human misjudgment. Embedded throughout his speech is the core role incentives play in influencing human behavior. One does not require a PhD in psychology to understand why corporate executives continue to expand stock buybacks at, counter-intuitively, record high stock valuations. The latest reminder of such incentives comes from The Center for Effective Government and Institute for Policy Studies. In a recent study they found that the retirement funds of the chief executives of the 100 largest corporations are worth on average just under $50 million, or a combined $4.9 billion. This amount is equal to the aggregate retirement accounts of 41% of U.S. families.

Stunning facts like that compel 720 Global to continue to raise awareness regarding the dangers stock buybacks impose not only on American public companies and their investors but also on the economic and social fabric of the nation. In part 1 of this series, “Buybacks: Connecting Dots to the F-Word”, 720 Global highlighted how executive leadership has elected to engage in uses of their corporate resources that benefit executive compensation at the expense of long-term shareholders, the company’s future success and ultimately the U.S. economy. Part 2, “Shorting the Buyback Contradiction”, examined the ways in which stock buybacks distort equity valuations and exposed the unknown risks being shouldered by investors.

This third article in the series extends the analysis of the prior two articles. It provides a more specific review of the ways in which corporations are manipulating their stock price and abusing the trust of investors to the direct benefit of corporate executives.

Corporate America and American Values – The Backdrop

Well before the Revolutionary War, commerce and trade in the American colonies was vibrant. By the early 1700’s, the colonies under British rule had rapidly become one of the most productive and wealthiest economies in the world, providing Great Britain with an invaluable source of trade goods as well as an increasingly powerful tax base for revenue. Naturally, those businesses – farming, manufacturing, printing and journalism, education, import/export – have evolved into what we know today as the domestic corporate sector. As corporate America grows stronger, more profitable and more powerful and influential, logic follows that this is a reflection of the durability and steadfastness of America. That is as it has always been.

These businesses, and their now global success are a manifestation of something immensely larger than that of the profits and material benefits they generate. The foundation of this country was conceived, established, dedicated and founded by good, brave men whom we today endearingly and reverently refer to as our Founding Fathers. By them, the United States of America was founded for a multitude of express purposes which cumulatively represent a set of moral ideals. From these established ideals, more than any other country in the history of mankind, much happiness and success has been derived. The fact that the United States of America was established as a republic, a nation based on the rule of law, amplifies the obligation of the population, especially leaders of all forms, in adhering to those moral ideals.

Reinforcing this concept in his first inaugural address to the population of the new republic, George Washington warned “…the propitious smiles of heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right which heaven itself has ordained.” And yet, for all of that foundation and obligation and reverence to which we owe our remarkable success, the traditional mechanisms by which we measure that success are failing.

Executive Greed

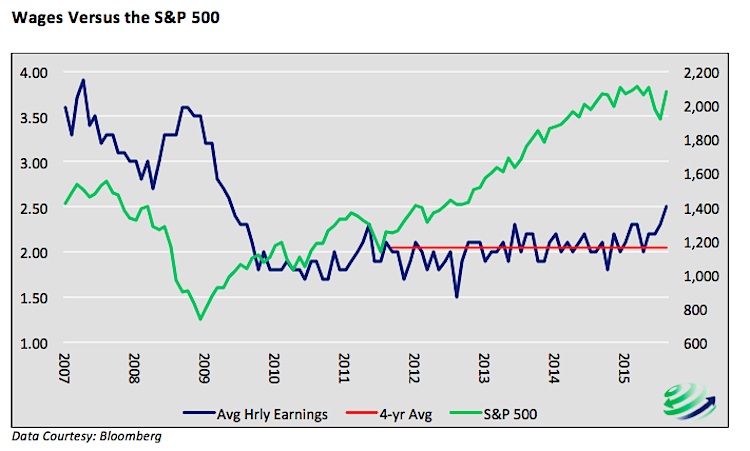

Today, corporate profits and U.S. stock markets, two of our broadest yardsticks for measuring economic success, are near record highs. On those metrics, one might be tempted to suppose that the strength of America is reflected in the strength and success of its businesses. And yet, corporate profitability and rising stock markets are not translating into widespread economic prosperity as shown in the graph below comparing stagnating hourly earnings versus the S&P 500.

Vast swaths of the population in the United States are not enjoying the benefits of the so-called post-crisis recovery. Meanwhile, the top executives of major corporations are prospering in a way never before seen. This contrast between the rich becoming ultra-rich and the rest of the population stagnating at best, was a characteristic of the pre-depression “Roaring 20’s” as well.

A report issued by the Economic Policy Institute on CEO pay highlights that in 2014 the CEO-to-worker compensation ratio was 303X compared with 58x in 1989 and 20X in 1965. The exponential rise in executive compensation has occurred in both relative and absolute terms. From 1978 to 2014, inflation-adjusted CEO compensation increased 997 percent, almost double the rise in stock market value. When compared with other highly paid workers (defined as those earning more than 99.9% of other wage earners), CEO compensation was 5.84 times greater. The rate at which CEO compensation outpaced the top 0.1% of wage earners reflects the power of CEO’s to extract “concessions” rather than an outsized contribution to productivity.

The composition of executive pay has gone from one predominately salary based with less than 15% stock and option rewards in the mid-1960’s to one heavily dependent on stock and option rewards averaging well over 80% in 2013. These stock-based incentives make executives highly motivated to keep their stock price elevated at all costs. The compensation structure in conjunction with the rise in pressure from Wall Street and investors to keep stock prices elevated arguably leads to short-term decision-making that ultimately does not afford proper consideration of the long-term problems those decisions create.

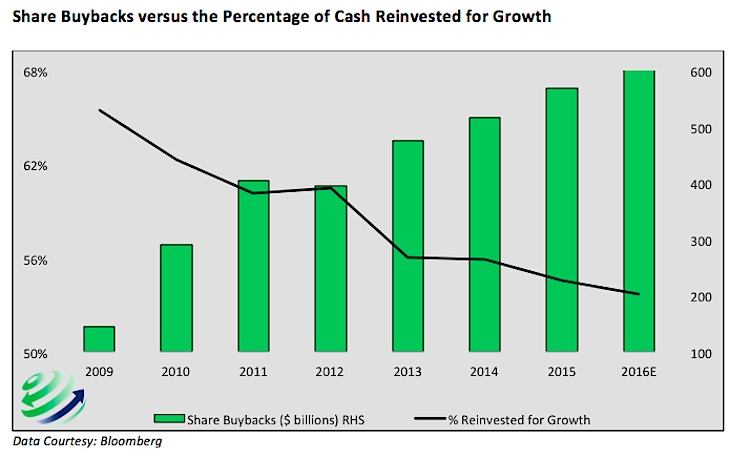

One of the most prevalent ways in which executives can carry out such a compensation-maximizing scheme is through share buybacks. Share buybacks as a percentage of corporate use of cash are at near-record levels and rising rapidly. In a market where all major indices and the majority of publicly-traded company shares are near all-time highs, the proper question is, why? As Warren Buffett wrote in his 1999 letter to shareholders, “Managements, however, seem to follow this perverse activity (buy high, sell low) very cheerfully.” As outlined in Part 1 on this topic, Connecting Dots to the F-Word, the three reasons CEO’s give to justify this action do not stand on their own. The purpose of this article is to explore more deeply, as a point of emphasis, the backdrop which allows such activity to proliferate and to further expose the “chicanery” (Buffett’s word) being employed by corporate executives in continuing to engage in share buybacks in defiance of sound business practices.

In 2007, companies in the S&P 500 returned over one-third of their cash, $635 billion, to shareholders through buybacks as shown below. At the time, this played a meaningful role in helping to elevate equity market valuations into the teeth of the subsequent financial crisis when stocks fell by over 50%. Now in 2015, share buybacks are expected to rise 18% on a year-over-year basis. Like 2007, corporations will again spend nearly one-third of cash, over $600 billion, on share buybacks. The growing popularity of stock buybacks is graphed below along with the disturbing trend in the percentage of cash invested for future growth. Similarly, stock valuations measured several different ways rival levels only seen with the exuberance of 1929, 2000, and 2007.

continue reading on the next page…